LIVES OF THE LAW

LIVES OF THE LAW

selected essays and speeches

20002010

TOM BINGHAM

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

T. Bingham 2011

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

Crown copyright material is reproduced under Class Licence

Number C01P0000148 with the permission of OPSI

and the Queens Printer for Scotland

First published 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

ISBN 9780199697304

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Introduction

Professor Sir Jeffrey Jowell KCMG QC

W hen Tom Bingham retired as Senior Law Lord in 2008 he was accorded an outpouring of respect which few judges have ever received. There have been a number of outstanding judges of recent vintage, possibly some of the greatest we have ever had, but there is little doubt that a poll of knowledgeable lawyers would overwhelmingly vote Bingham the greatest of his generation.

This universal admiration is all the more surprising as Tom Bingham presided at a time when the relationship between the judiciary and Parliament was often more tense than it had ever been. The courts overturned the actions of the executive more frequently than they had done in the past. In response, politicians at the highest level were openly disrespectful of the legitimacy or competence of unelected judges to challenge their designs.

The essays in this book demonstrate why Tom Binghams authority prevailed during those difficult times. In accessible style he draws the reader into the historical and social context of an issue. He meticulously presents arguments for and against the matter and, having come out on one side or another, is never hectoring or sanctimonious. Above all, he captures the spirit of liberty and the rule of law which are the foundations of the British legal culture and which rest, in his view, upon a set of simple and obvious values and practices. Yet he is never narrowly parochial, accepting as he passionately does the imperative to observe the rule of law in both a national and international context and drawing on examples of good and bad from countries as disparate as Pakistan and India to South Africa, France, Australia, Israel, New Zealand and the USA.

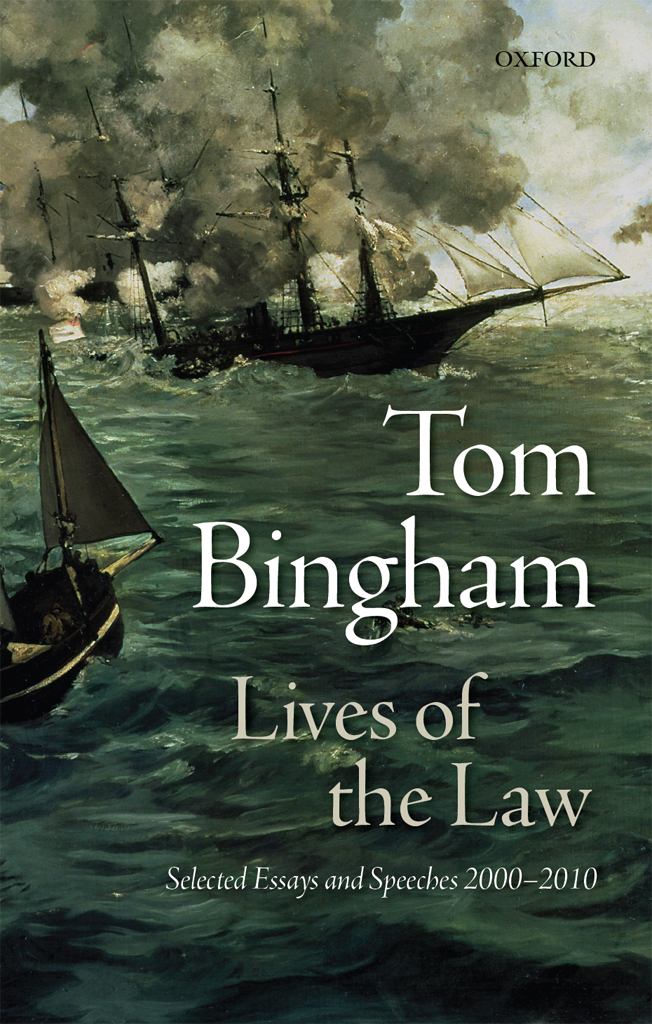

This book will not date easily, for two reasons. First, some of the chapters deal with not only with wonderfully readable accounts of key thinkers about our law and constitution, such as Dicey, Bentham and even Dr Johnson. They also look back at key moments in our constitutional history, such as Magna Carta, the development of habeas corpus and the abolition of slavery. There is also a fascinating chapter which meticulously traces the history of the Alabama claims. This chapter is rightly placed in the section in the book on the rule of law, as Bingham sees the arbitration of that dispute (about the partisan role of British- built ships during the American Civil War) as heralding the development of what he calls international rule of law. At Binghams memorial service in May 2011, Lord Mackay remarked that Tom Bingham had considered himself an historian manque, which is so evident from these lively sketches which enlighten many of the fundamental questions surrounding our current constitutional dilemmas.

Secondly, the book is shot through with an issue that will always persist, namely, the delicate and difficult relationship between the courts and other branches of government. At the time of writing this issue has once again raised itself in the media, with politicians questioning the power of courts to extend rights to personal privacy against press freedom, and criticising the so-called usurpation of their functions, especially when judges liberally interpret the European Convention on Human Rights.

These constitutional skirmishes are by no means new. In the 1980s Lord Dennings court was taken to task for striking down a popular measure by the Greater London Council to reduce transport fares. In the 1990s Home Secretary Michael Howard berated the judges for striking down his attempts to impose tougher prison sentences. President Mandela of South Africa famously declared himself glad when his new Constitutional Court overturned one of his decisions, on the ground that this demonstrated that no-one in the new South Africa was above the law. Alas, this example is lost on most politicians who, perhaps naturally, refuse meekly to accept the reprimand of a court without countering with an assertion of their own superior legitimacy and competence to decide the matter in question. Some have dubbed judges innately conservative. Others see them as inappropriately activist. Bingham has little time for these labels, showing how decisions of the courts have disappointed as well as delighted claimants against the state. Decisions which favour unpopular minorities tend to be unpopular. So do decisions which disfavour popular causes (such as the lowering of transport fares).

In explaining the judicial role, Bingham does not adopt the conventional assertion that the legislature makes law and the courts apply the law. He is alive to the fact that judges are not a neutral colourless medium through ).

In some countries, courts which have held against the government in key cases have had their powers curtailed (as is about to happen in Hungary) or even suspended (a fate that has recently befallen the new Southern African Development Communitys Tribunal, which had the temerity to rule against the tyrant Mugabe of Zimbabwe). Surprisingly perhaps, in view of his passion for the rule of law, Bingham would allow Parliament the ultimate power even to abolish judicial review, believing as he does, with Dicey, that the sovereignty of Parliament is our prime constitutional principle. However, as he simply says, countries which defy the rule of law in such a manner are places where he would prefer not to live.