PRECIOUS CARGO

Copyright by Dave DeWitt 2014

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available

ISBN 978-1-61902-388-8

Book design by Lois Manno

COUNTERPOINT

1919 Fifth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Illustration on previous page: Three Maize Cobs (India Corn). Engraving by Anga Bottione-Rossi, 1835. Sunbelt Archives.

Hypotheses about past events are not susceptible to scientific proofs, and the historian can never hope to have a hypothesis certified as anything better than reasonable. He must lope along where scientists fear to tread.

Alfred W. Crosby, Jr., in The Columbian Exchange, 1972

To my favorite food historians: Sophie Coe, Karen Hess, Mark Kurlansky, Waverly Root, and Andrew F. Smith.

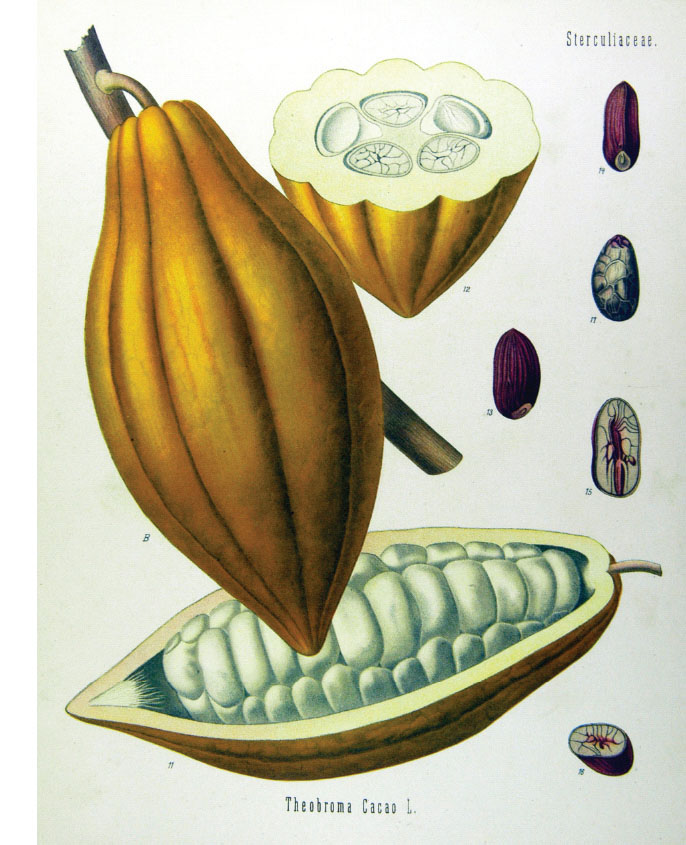

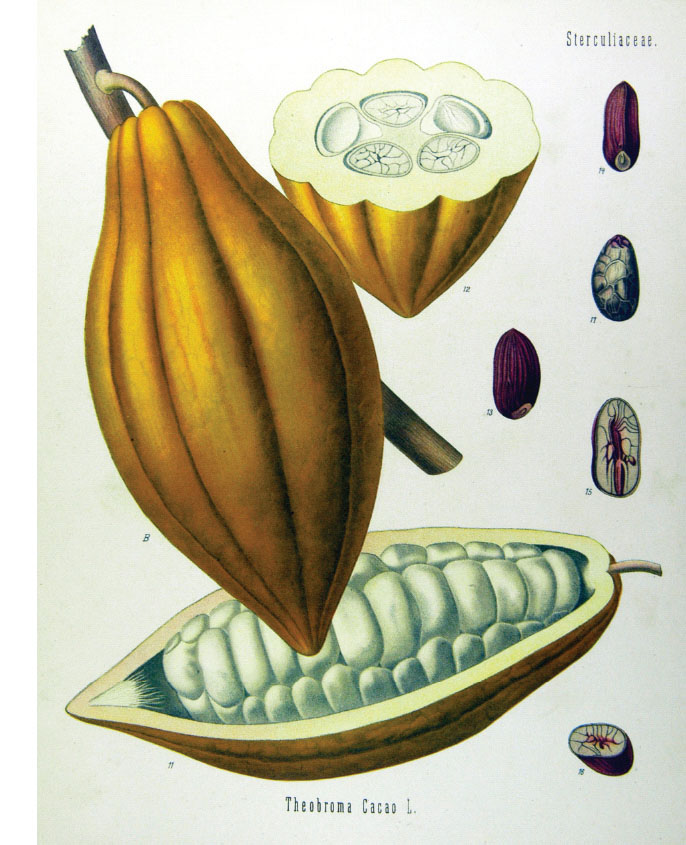

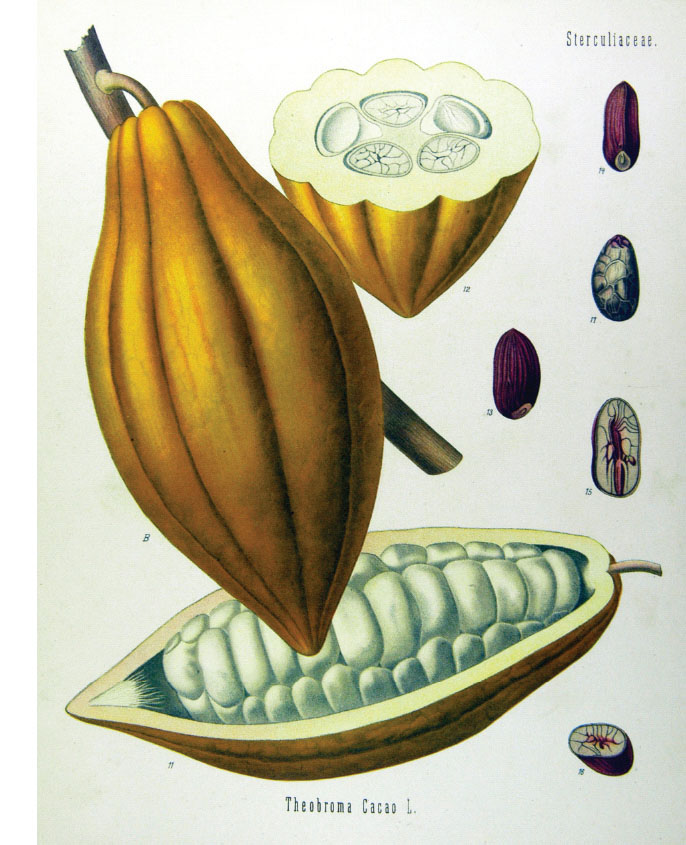

Theobroma cacao (Chocolate), by Franz Eugen Khler, 1897. Sunbelt Archives.

CONTENTS

I was mostly on my own for this project, but I did receive a lot of help from Dean Elizabeth Titus and her staff at the New Mexico State University Library, along with assistance from Rick Browne, Pat Chapman, Marco Del Freo, Lois Manno, Richard Sterling, and Harald Zoschke. A special thanks to my agent, Scott Mendel, who never gives up. And a big abrazo to editor Jack Shoemaker of Counterpoint, who really believed in this book from his first reading of it.

Chile Peppers. Botanical illustration by Ernst Benary, 1876. Sunbelt Archives.

For the past quarter century, Ive been just a little bit preoccupied with chile peppers, and that obsession has driven me to create two magazines, more than thirty books, a major trade show now in its twenty-sixth year, and a large online archive that is the Fiery Foods & Barbecue SuperSite. After I completed my part of The Complete Chile Pepper Book (2009), I searched for a food history project with a broader scope than my previous two books in that genre hadnamely an alternative history of Italian cuisine and then the story of the historical food lovers who launched what is now American cuisine. My work on the first one, Da Vincis Kitchen (2006), which Im proud to say has been published in fourteen languages so far, got me thinking about how New World crops beyond chile peppers influenced other worldwide cuisines. This time, my new project involved chile peppers as only one crop among all the New World foods transferred to the Old World that were destined to change the history of civilization.

So this book is not about American food but rather American foodsthe lowly crops that became commodities, and one gobbling protein source, the turkeyand how these foreign and often suspicious temptations were transported around the world and eventually changed not only cuisines but the very fabric of human life on the planet. Many books have been written on each and every food topic Im covering, but the entire story has never been properly told. To tell it, I had to dig rather deeply into food and popular history, plus numerous other disciplines, a task that would not have been possible without two invaluable resources: Google Books and the New Mexico State University Library and its connections to libraries all over the world.

What I enjoyed the most about researching this book was discovering the cross-disciplinary nature of food history. Its a lot more than just history and recipes, so I had to delve into botany, zoology, anthropology, and archeology, to name the more important disciplines I investigated to complete the research. For example, the archaeological excavations Cern, the American Pompeii, proved that most of the early Spanish descriptions of the crops and foods of the New Worldoften derided throughout timewere dead-on accurate. I also loved telling the tales of those surprising individuals who were caught up in the spread and influence of American foods, including a slave trader, a physician and African explorer, several brutish conquerors, the Indiana Jones of Southeast Asia, a Scottish millionaire obsessed with a single fruit, and a British Lord and colonial governor with a passion for peppers, to name a few.

Enjoy the journey.

Discovery, Botany, and Food Evolution

Proponents of localized food production, often called locavores, are opposed to food globalization, and many of them believe that this spread and exchange of foods is a trend unique to the modern era. This is simply not true. The subtitle of Kenneth F. Kiples book A Movable Feast is Ten Millennia of Food Globalization, and he notes that food globalization began with the invention of agriculture some ten thousand years ago in at least seven independent centers of plant and animal domestication.

In one example that I discussed in depth in Da Vincis Kitchen, were it not for food globalization and the introduction of durum wheat, maize, rice, tomatoes, and sugar into Italy at different times, the cuisine of that country would be far different from what it is today, lacking pasta, polenta, risotto, marinara sauce, and tiramisu. But arguably the most significant globalization event in history was the Columbian exchange of New World and Old World foods and culinary techniques, which made an enormous impact on population growth, famine avoidance, and a new direction in the evolution of major cuisines of the worlds diverse regions. This transfer of plants, animals, foods, slaves, settlers, diseases, and culture between the hemispheres is one of the most significant worldwide events in human history concerning ecology, agriculture, and culture. And these momentous events began with what is called The Age of Discovery.

The quest for spices and the need to eliminate Arab middlemen from that lucrative trade were the motivating factors driving the search for alternative routes to the Indies so that European traders could deal directly with the spice sources. The Portuguese led the way by exploring the Atlantic coast of Africa from 1418, under the sponsorship of Prince Henry the Navigator, and reached the Indian Ocean by 1488. The Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 divided the world into two parts, the western part for Spain and the eastern section, including Brazil, for Portugal. Although that treaty prevented war between Spain and Portugal, it eventually backfired, according to historian Stephen R. Bown. It was to have a profound influence on world history, he wrote in

Next page