For Nicholas Carroll and John Eastman, the true believers.

There are no foreign lands.

It is the traveller only who is foreign.

Robert Louis Stevenson

Three sheets to the wind

Informal. very drunk

Sheets are ropes (and occasionally chains) used to hold the lower

corners of sails in place. If three sheets are loose and blowing about

in the wind, then the sails will flap and the boat will lurch about like

a drunken sailor. The original phrase was three sheets in the wind.

Contents

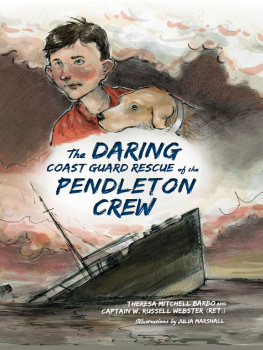

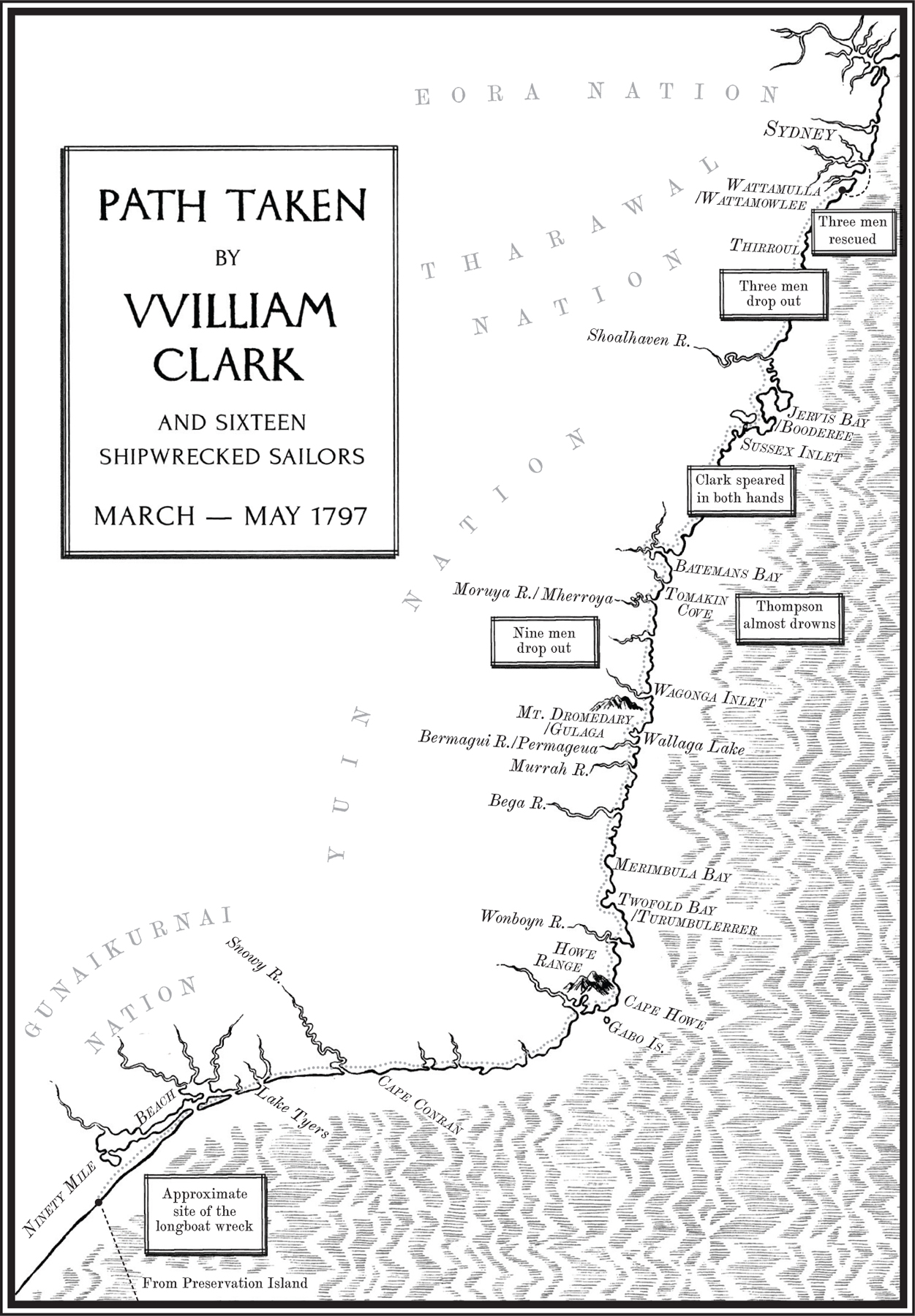

T HERE ON ONE of the continents longest stretches of beach, seventeen disoriented and exhausted men, their bodies encrusted in salt and sand, fell asleep under an autumn sun. When most had regained consciousness later in the day, the turmoil of the morning had been replaced by a stillness of water and wind and the return of bird noise. Mutton birds and seagulls now patrolled the waters which had nearly killed them all a few hours earlier.

Still dazed, the crew looked around to see a thin but infinite strip of sand curving gracefully from east to west. At the back of the beach, green-topped sand dunes stood like natural ramparts, built up over time to rebuff concerted attacks from the ocean. What was left of the longboat littered the foreshore, its contents thrown along the sandy strip.

It was such an enormous expanse of beach that none could quite take it all in. This was not the muddy and craggy Scottish shores of Arran that William Clark would have known. The Indian sailors, too, had never seen any coast so vast and yet so remote and lonely. There were no cultural or geographic touchstones on Ninety Mile Beach in 1797. To their eyes it was the beach at nowhere that led to nowhere.

It was their first experience of mainland Australia and already they had marked it, as so many coming after them would, with their refuse. They spent the first three days searching for anything that could keep them alive and, in this, they were considerably lucky. At the high tide mark, among the stubs of vegetation and tangled scrolls of kelp, they found many of the bags of rice that would have fed them on the sea voyage. It could still be dried and eaten. Now it would have to sustain them for a very long trek.

Most of the water casks were also found intact, with fresh water still in them. Survival, at least for the short to medium term, looked possible, but in other ways, their plight was desperate. The longboat which had brought them across Bass Strait was irretrievably broken. The carpenter lacked special tools to fix the sprung planks and shattered timber frame. Of all the things that had been retained, Hugh Thompsons compass was among the most valuable. He had kept it close to his person and dry. It was a survival tool in itself. It was meant for the ocean, but would make some sense of a featureless landscape. And yet what it now told him made no sense.

The beach was running in an east-north-east direction, and appeared to be arcing more easterly in the direction they needed to take. The sun rose at one end of the beach, and set at the other. This was not what the official maps illustrated. If these had been correct, this beach should be running from south to north. The maps had to be wrong.

They had recovered two pistols, a musket and swords from the wreck, albeit the guns would probably be useless as the gunpowder could not have survived the wreck of the longboat. They also redeemed axes, knives and cooking pots from the wreck as well as the water containers and bolts of calico cloth. William Clark thought these might be useful, but he wasnt sure how. Perhaps they could be used for barter? They had found useable tinder and flint. Indeed, they took anything they could salvage from the beach.

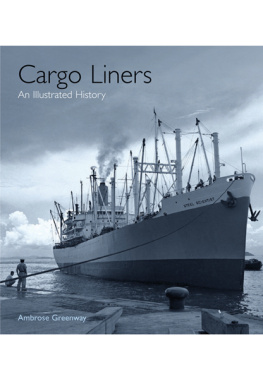

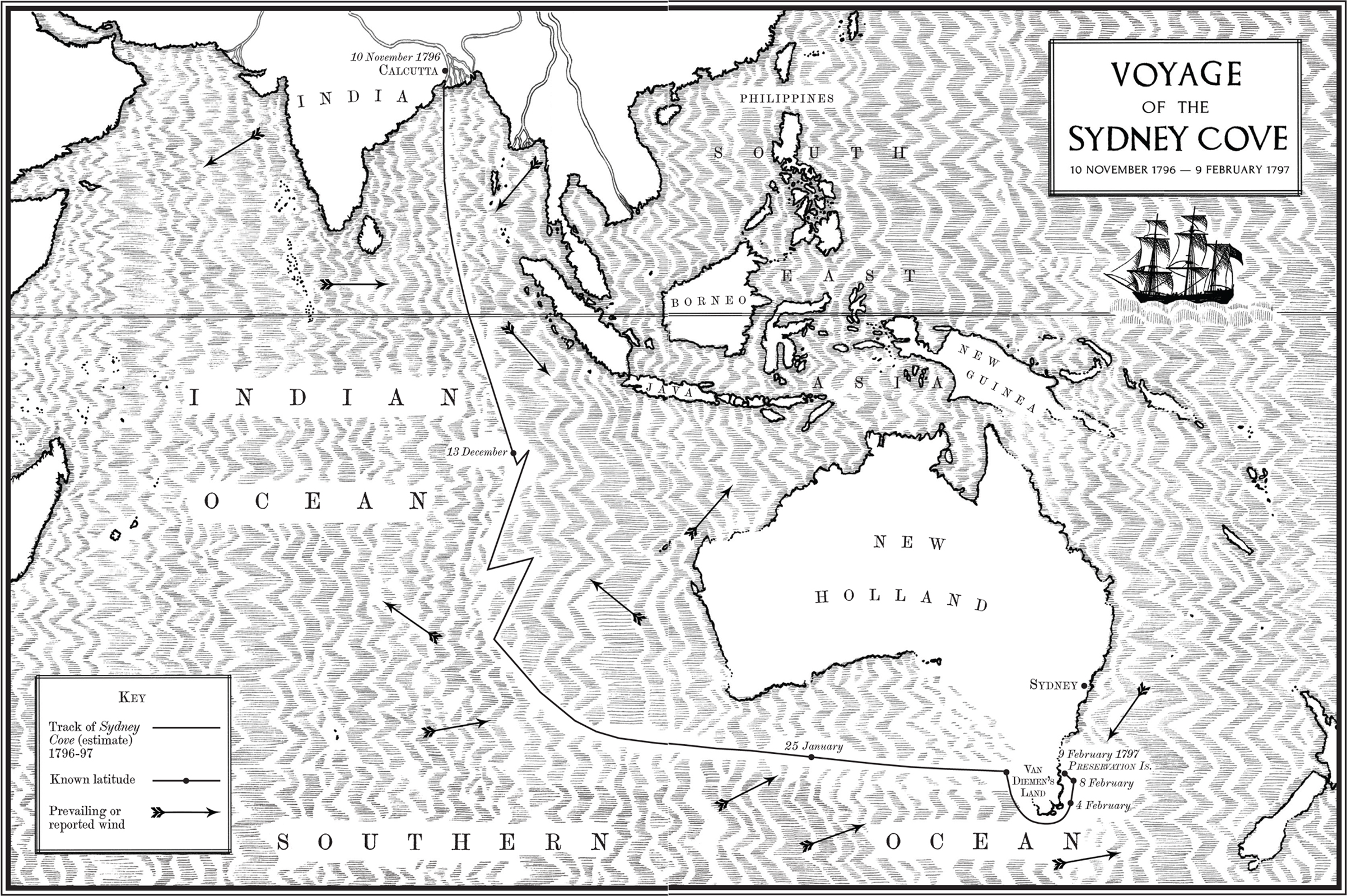

Clark was the man in charge of the 7000 gallons of rum they were bringing to Port Jackson. He had wanted to be at the trading vanguard, first to strike a profitable, ongoing relationship between Calcutta and Sydney. That was the great hope. Fifty-five men had sailed on the Sydney Cove on a simple bet: that a colony made up of soldiers and felons would kill for a taste of the best Bengali rum.

The problem, of course, was that nobody in Sydney knew they were coming. The voyage to the colony was speculative and their hundred-foot, three-masted ship had never sailed further than the main ports around Asia and the Persian Gulf. It had never crossed the Indian Ocean. Very few in India had made this voyage. They were sailing on a hunch, equipped with a faulty map and little knowledge of the conditions ahead of them.

Their Indian sailors, who had laughed and sung in the face of tropical storms, had recoiled at the freezing winds and waters of the southern Australian coastline and yet it was they who had saved their lives and the cargo. The very fact that there were seventeen men alive and breathing on this beach had been a miracle grounded on the sweat and blood of Indian mariners.

Clark looked at the state of the men he was now about to take through the wilderness. Many of the men appeared shaken, pale and sick. They had survived two shipwrecks in succession. He wanted to move them out the next day and get to Port Jackson before the winter set in, but moving was clearly not even being contemplated. The party was unusually quiet and nobody strayed far from their makeshift camp.

It dawned on him that it wasnt their bodies that couldnt move but their minds. Seamen were more anxious about land than they were about the sea. Clark had been a virtual spectator at sea, almost incredulous at the speed and agility of the Indians, virtual acrobats aloft, whose combined actions could change the ships bearing in a matter of moments.

Where had all that gone now? The sea was the danger they did know, the land especially this particularly silent and unrelenting land held unknown terrors. Cannibals? Tigers? Crocodiles? Head hunters? The five Europeans and the twelve Indians had one thing in common they were all similarly ignorant. It was still the age of discovery, the literature and rumour of the day fed by nightmares and superstitions.

They were, in fact, in the middle of Gunaikurnai land; the country of the Gunaikurnai people spanned hundreds of miles to the north, west and east of them. It stretched as far as the Snowy River in the east and as far north as the Great Divide. Clark and his men did not know it, but already they were being watched.

Just how seventeen men expected to be adequately fed for a period of weeks, if not months, was beyond Clarks calculations. They had 500 miles of unknown territory ahead of them, and rationed rice for seventeen could only go so far.

It was all very simple in Clarks mind: he had no idea where he was but he knew what they must strive to do. Terra nullius was a notion they could not entertain. This was their unspoken dilemma: the very people they feared most were their only avenue of salvation.

W HEN WILLIAM CLARK stepped ashore in Calcutta one late afternoon in the summer of 1796, he could scarcely take in the scenes playing before him. He had disembarked at the Course, after a slow and precarious route up the Hooghly River. Together with men and women in their most extravagant finery, he walked the dusty boulevard, animals and birds walking freely among them.