Contents

Guide

To those who should be here: Nicholas Pfanner, Robert Foulcher,

Christopher Aylward, Philip Parker, Romaine Youdale, Matthew

Bracks, David Litherland, Harry McRitchie, Christopher Molnar,

Sam de Brito, Sheila Browne, Kelly Stoker, Jaime Robertson.

You are all greatly missed.

Its the first settlers do the brutal work. Them that come later, they get to sport about in polished boots and frockcoats, kidskin gloves... revel in polite conversation, deplore the folly of ill-manners, forget the past, invent some bullshit fable. Same as what happened in America. You want to see men at their worst, you follow the frontier.

Thaddeus Cuff, quoted in The Making of Martin Sparrow by Peter Cochrane

You see Mr Hull, Bank of Victoria, all this mine, all along here Derrimuts once.

Evidence given by Derrimut to magistrate William Hull, 1858

Contents

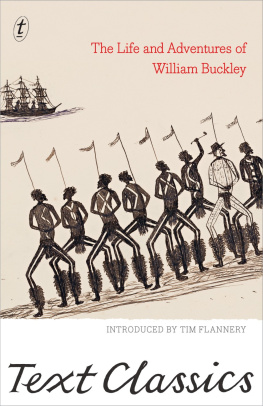

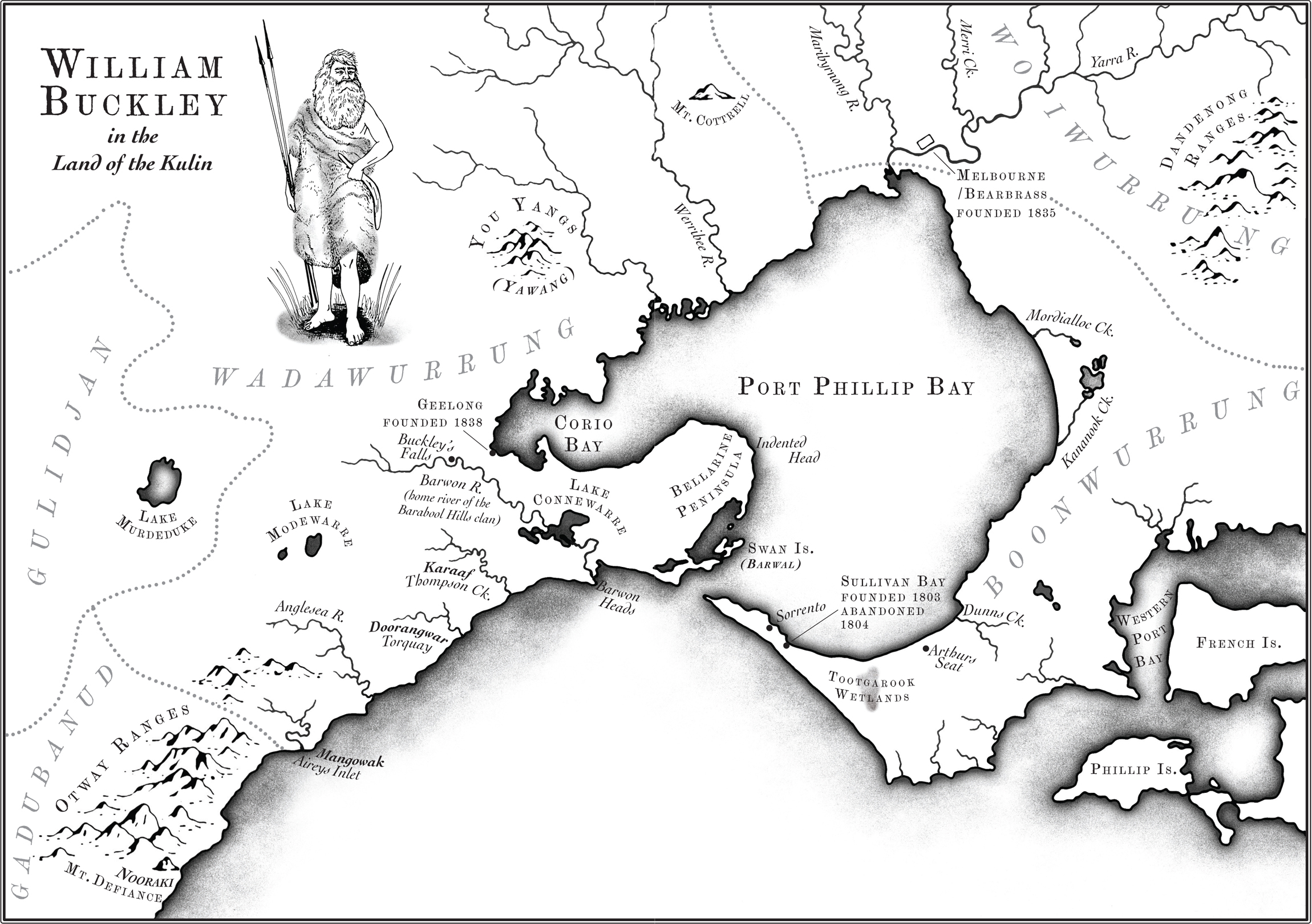

A T AROUND 2 p.m. on 6 July 1835, the ever-alert John Pigeon gasped and dropped his billy can. Pigeon was a well-travelled Aboriginal man from the southern coast of New South Wales. He had worked for the wealthy grazier John Batman in Van Diemens Land for nearly a decade, travelled and walked with many tribes throughout the continent, and lived with the Palawa and European sealers on the coast. He had seen many things, but he had never seen this.

A giant appeared at the far end of the camp who was so clearly a white man and so clearly not. He was the tallest and most powerful human Pigeon had ever laid eyes on. He was middle-aged, his complexion ruddy and sunburnt, his grey beard falling below his chest. He held his gaze on the eight men in camp, with just the slightest hint of suspicion.

The man was shoeless and dressed in well-worn possum skins. In his left hand he carried a giant mongeile, a double-barbed spear ten feet in height, the most feared of all weapons. In his right a waddy or club, known as the kudgeron, designed to strike opponents on the head. At his feet, he had a number of boomerang-shaped wonguim, the first recourse in battle designed to break legs and inflict heavy wounds. He held these implements lightly and deftly, the way Pigeons people did. His stance and bearing showed he knew how to use them, but his mien was unmistakably that of a white man. And yet only an Indigenous person could have come in so close to the camp without his noticing. White men knew nothing of stealth. Pigeon, one of Batmans most brilliant trackers, never missed a thing.

By Pigeons estimation, this man had the bearing of a white ngurungaeta, an elder man of knowledge. There was no other name for what he now saw.

In a few moments, everybody in the camp had seen the man. There were a few gasps, then nobody spoke. The three white and five Aboriginal men sat transfixed, looking in wonder at each other then back at the apparition. There was no alarm. Nobody rushed to their guns. Nobody moved. It was as if a spirit had come to visit them, floating in from a place nobody could quite divine, hovering for reasons none could understand. An astonishing spirit, but not a harmful one.

The giant betrayed no emotion. Soon he sat at the edge of the camp, not far from where Pigeon and his men had set up their tents. He was impassive, almost motionless, looking askance at everyone. His war and hunting implements were now propped between his legs.

Eventually the stunned silence wore off, and the sprightly James Gumm, an ex-convict from Southampton, walked over to the man and started talking. He showed no signs of comprehension; its probable he had some understanding of a working-class Hampshire accent, but his tongue movements in relation to his upper palate had changed since hed last spoken to a fellow white man. He couldnt remember let alone form the English words that had once come naturally. He also didnt want to say who he was not just yet. He first wanted to figure out if these men were friendly. They cut up a piece of bread and handed it over.

Then he remembered. He later described it as a cloud passing over his brain. Bread, he said. It was the first English word he had uttered in thirty-two years.

The eight men started calling out words and phrases that they thought their visitor should know. They thrust objects in front of him, waiting for him to come up with the correct English terms.

Gumm asked the man if he could measure his height. In his bare feet, Gumm measured him at six foot five inches and seven eighths not quite the height many have attributed to him at around six foot eight.

Gumm asked the question every man in camp must have had on his lips: Who are you?

Still somewhat tongue-tied, the man pointed to the tattoos on his right forearm: the letters W.B. alongside some basic renderings of the sun, the moon and something that looked like a mermaid with legs. William? asked Gumm. The man nodded. Gumm persisted on the B part of the puzzle but to no avail. Burgess? The man did not respond. As an ex-convict, Gumm thought he knew a roughly drawn convict tattoo when he saw one, but these ones could have belonged to a mariner. Whoever the huge man was, it was clear he preferred to keep his identity a mystery.

He remained cautious but found them pleasant company, as they offered him food and gestures of assurance. Their chattering brought back old memories, as did the food. The fried tinned meat sat heavily in his stomach and must have reminded him of army and convict life, but the tea and fresh bread spoke of something else, a lost memory of home and hearth. The small things bread, tea, salt and meat were inflaming his senses, arousing old feelings. His old life, and the words that bound and formed it, were slowly returning, but he could express very little.

Word by word I began to understand what they said, and soon understood as if by instinct that they had seen several of the native chiefs, with whom, as they said they had exchanged all sorts of things for land, he would later recount. That night, as his comprehension improved, he became increasingly alarmed at what he was hearing. These white people thought they had done a deal with the local Indigenous people, the Wadawurrung, and it related to a contract for landownership. I knew [this] could not have been... they [the Wadawurrung] have no chief claiming or possessing right over the soil: theirs only being as the heads of families.

He realised quickly enough that the whites who knew nothing of the value of the country had duped the people he had lived with, who had nurtured him for decades. I therefore looked upon the land dealing spoken of as another hoax of the white man. He had come here to warn the newcomers that they were in trouble, yet they had some strange notion that they had made a deal giving them protection.

The man knew nobody came onto Wadawurrung land without permission. This act required plenty of parley and plenty of gifts, and a readiness to have more to spare. He knew these transgressors had no idea that within a day or two, hundreds of Wadawurrung would be demanding huge compensation for their presence.

Only Pigeon understood. He was the big mans opposite: a black man who had lived with whites, who was now being asked by his white master to entreat with black people again. This had not been lost on Pigeon. Like himself, the mysterious man was a messenger, but Pigeons job was to sow peace while the man brought tidings of war. Pigeon knew Batman had a very weak toehold on a strip of beach on the Bellarine Peninsula; he had not, in fact, signed a contract with the Wadawurrung people.

Next page