WILLIAM BUCKLEY was born in 1780 near Macclesfield, in northern England. The son of a farmer, he became a soldier and was wounded in action in 1799. In 1803 he was shipped to Australia on the Calcutta, having been sentenced the year before to transportation for life for possessing stolen cloth.

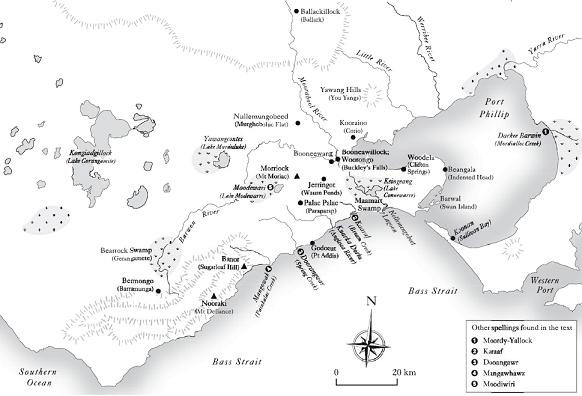

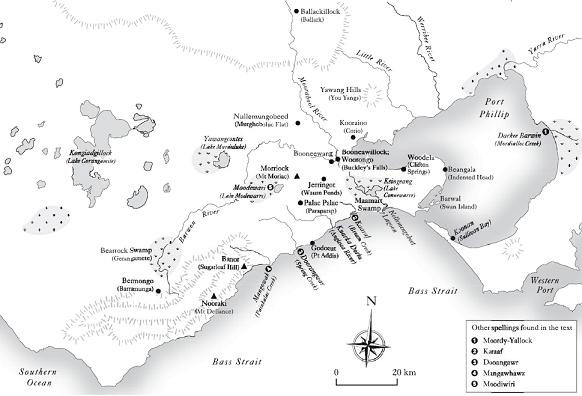

Buckley and two other men escaped confinement at the Port Phillip camp under Lieutenant-Governor David Collins. Though his companions turned back, hungry and desperate, Buckley remained at large, surviving on food he foraged around Port Phillip Bay. He was befriended by people of the local Wathaurong tribe, adopting their customs and learning their language, and lived in a hut at Bream Creek.

Three decades later, in 1835, Buckley finally gave himself up. He was pardoned and John Batman made him an interpreter for Aboriginal tribes of the region, but in 1837 Buckley went to Hobart.

There he married, and worked for almost a decade as gatekeeper of the Female Factory. He retired in 1850; two years later the newspaper editor John Morgan published Buckleys account of his years as the wild white man.

William Buckley died in 1856.

TIM FLANNERY is a bestselling writer, scientist and explorer. He has published over thirty books, most recently Sunlight and Seaweed: An Argument for How to Feed, Power and Clean Up the World. In 2013 he founded the Australian Climate Council.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Sincere thanks to Dr Betty Meehan, Dr Les Hiatt and Dr Alexandra Szalay for their thoughtful and timely comments on the introduction. Any remaining errors are, of course, the full responsibility of the author.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

by Tim Flannery

Preface to the original edition

by John Morgan

The Life and Adventures of

William Buckley

Reminiscence of Buckley

by George Langhorne

BY TIM FLANNERY

A t 2 pm on Sunday, 6 July 1835, a giant of a man shambled into the camp left by John Batman at Indented Head near Geelong. Batman had departed for Van Diemens Land to prepare a full-scale migration to his new settlement in the wild country around Port Phillip Bay, but the figure that entered his camp that day was a reminder that the regions European history had begun long before. An astonished Jim Gumm, who had been left in charge by Batman, measured the stranger, discovering that he was six foot five and seven-eighths inches tall (198 centimetres) in his bare feet. Though clearly a European, and well proportioned with an erect military gait the visitor spoke not a word of English. Instead, he pointed to a tattoo on his arm, which bore the initials WB alongside crudely executed figures of the sun, moon and a possum-like creature. Then, when he was given a slice from a loaf, the word bread broke suddenlyalmost involuntarily from his lips.

Over the following weeks, as his mother tongue slowly returned to him, fragments of the strangers history were revealed. His name, he said, was William Buckley, and he had been living with the Aborigines for so long he had lost track of time. At first he claimed to be a shipwrecked sailor, but then admitted that he was a runaway convict and begged for a pardon. What he told of his life in the Victorian bush so amazed those who heard him that he soon became celebrated as the wild white man. He was, according to his contemporary and biographer James Bonwick, one of the most wonderful characters that Australian history has ever produced.

Buckleys sudden appearance astonished many because for the previous thirty-two years he had been presumed deadperished miserably in the woods according to Lieutenant-Governor David Collins. Yet all the while he had been living with the Aboriginal tribes of western Victoria. With them he had travelled hundreds of kilometres into the hinterland (as yet unexplored by Europeans), experienced tribal wars, witnessed mysterious ceremonies, and even claimed to have seen the fabulous bunyip.

So great was public demand for Buckleys story that shortly after his discovery an entrepreneur almost tricked him into becoming a sort of theatrical freak show, until the horrified Buckley realised what the game was. He was hardly more co-operative with newspapermen, some of whom assiduously applied the steamy vapour of the punchbowl in an effort to prise his story from him. It was in vain also that august personages such as George Arthur, lieutenant-governor of Van Diemens Land, made inquiry. Even Governor Richard Bourke himself, who took time out from naming the village of Melbourne to meet with the local celebrity, received just a couple of monosyllables in reply to his numerous and earnest questions. Over the years it was to become a familiar pattern. It mattered not whom the inquirer was, nor whether the questions were learned or salaciousall came away frustrated. John Pascoe Fawkner, one of Victorias earliest and most illustrious settlers, was perhaps not alone in thundering, after meeting Buckley, that the man was a mindless lump of matter.

And yet, unknown to everyone it seems, Buckley had spoken of his adventures. Shortly after he came into the camp at Indented Head he had confided in the Reverend George Langhorne, a missionary whom he was seconded to work under as interpreter, at the salary of 50 per year. Langhorne found that obtaining Buckleys story was extremely irksomeas I frequently had to frame my queries in the most simple form, [Buckleys] knowledge of his mother tongue being very imperfect at the time. The account, which was later transcribed onto just four closely typed pages, remained buried treasure for nearly eighty years. When discovered and published in the Age in 1911 it would revolutionise our understanding of Buckley and his experiences.

As a result of his silence and of comments such as Fawkners, Buckley has come to be thought of as a dull-witted giant. Such a man, however, could never have survived the things that fate threw at William Buckley. He may have been poorly educated, but his narrative reveals him as a resourceful and adaptable fellow of some perception and intellect who managed to learn at least one Aboriginal language near-perfectly. It is hard to be sure why Buckley remained tight-lipped for so long. Perhaps he was just sick and tired of being treated as a freak, or maybe his life as a soldier, then a convict, had taught him the virtue of keeping his mouth shut. In a frontier settlement like early Melbourne the habit would have served him well, for rumours about him were rife. John Pascoe Fawkner accused him of conniving with the Aborigines to kill shepherds and steal sheep, while the surveyor John Wedge spread the word that he had been transported for attempting to assassinate the Duke of Kent at Gibraltar!

When The Life and Adventures of William Buckley was finally published in 1852, seventeen years after he had wandered in from the wilderness, it was with the patronage of John Morgan, a Tasmanian newspaper editor who had convinced Buckley to collaborate in producing the book. Its difficult to determine just how much influence Morgan had in shaping this remarkable autobiography, but there are reasons to assume that his editorialising was extensivefor Buckley was only semiliterate, and he agreed that Morgan should share the profits from the work.

Next page