This book has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of Marguerite and Gerry Lenfest.

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

2014 by Andrew Faltum

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Faltum, Andrew,

The supercarriers : the Forrestal and Kitty Hawk classes / Andrew Faltum.

1 online resource.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed.

ISBN 978-1-61251-770-4 (epub) 1. Aircraft carriersUnited StatesHistory. 2. Kitty Hawk (Aircraft carrier) 3. Forrestal (Aircraft carrier) I. Title.

V874.3

359.9435dc23

2014023682

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs are official United States Navy photographs.

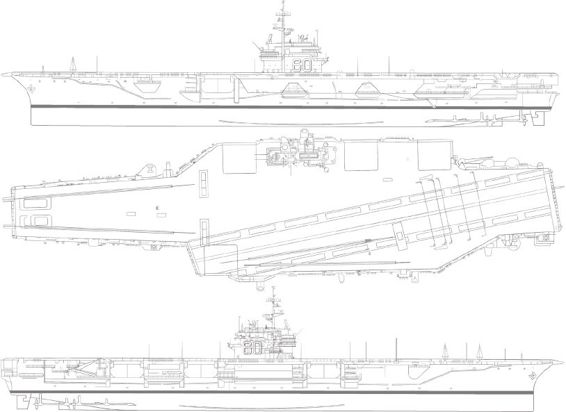

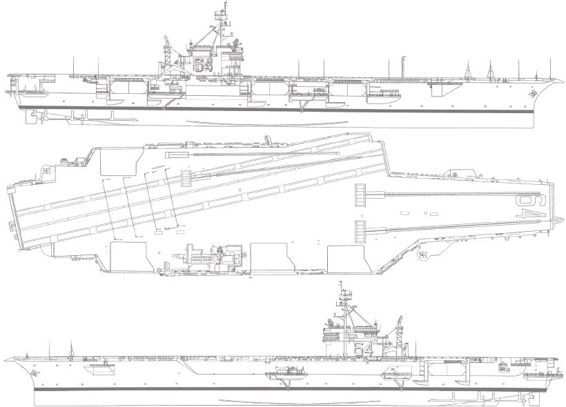

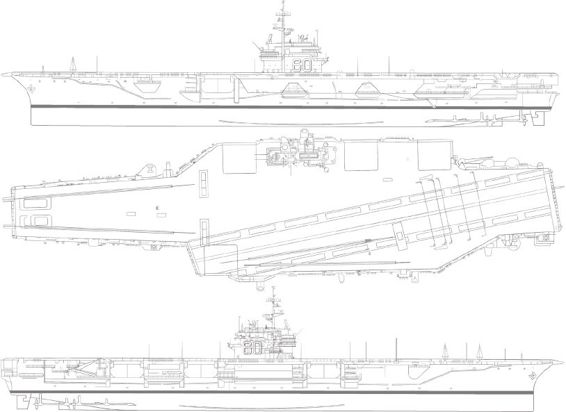

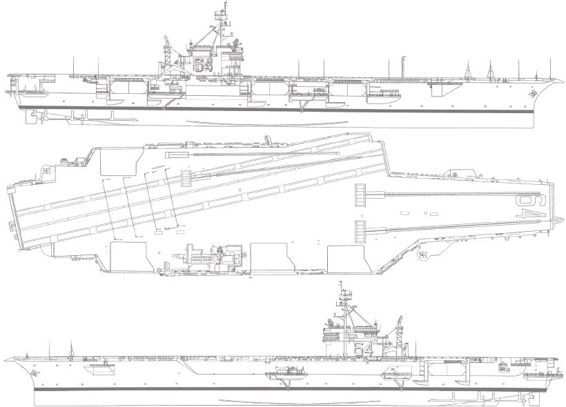

The front end paper depicts the Saratoga late in her career as a representative of the Forrestal class. The back end paper of the Constellation represents the Kitty Hawk class. Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations are the works of the author.

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First printing

Contents

I n 1955, when the USS Forrestal was commissioned, it ushered in a new era of naval power as the first of the super carriers. Throughout the Cold War and into the uncertain and dangerous world that followed, the first question of senior American leadership in response to a crisis has often been, Where are the carriers? The Forrestal and the carriers that followed her have played a significant role in world affairs for more than fifty years. Although it is customary for the later ships to be treated as separate classes, this book will address all the conventionally powered aircraft carriers as a group and show their evolution through changing operational requirements and developing technology.

As a boy, I was fascinated with naval aviation and aircraft carriers and built many plastic models of various carriers, particularly the Forrestal herself. Later in life, on active duty as an air intelligence officer, I served on the Midway home ported in Yokosuka, Japan. I subsequently remained in the Naval Reserve Intelligence Program until retiring in 1995. One of my last active duty for training assignments was to spend two weeks on board the Saratoga on one of her last at sea periods before her own retirement. Since I was not part of the ships company or assigned to the air wing, my duties involved an operational orientation that a senior commander would not normally receive. It was an indelible experience. It is difficult to explain to anyone who has never gone to sea in a warship, but in writing this book, as in my previous works, I have tried to convey how such a complex thing as an aircraft carrier works and how her crew brings its aircraft, weapons, and components to life. Technical jargon has been avoided where possible, but technical information has been included in the appendices as appropriate. For those with no military experience, an explanation of some of the conventions used in this book is in order. Dates and times are given in military fashion, that is 1 October 1955, rather than October 1, 1955, and 1300 instead of 1:00 p.m. Unless stated otherwise, all dates and times are local and all distances are in nautical miles. This book has been compiled from many sources and though I have tried to resolve any conflicting information wherever possible, any errors in judgment are ultimately mine.

T he ships of the Forrestal class became the first super carriers specifically designed to operate jet aircraft to enter service. The basic soundness of design can be seen from the fact that they became the basis for every U.S. carrier that followed. (The ships of the Kitty Hawk class were essentially improved Forrestal designs.) To understand how the Forrestal and subsequent ships came about, it is necessary to first look at the evolution of carrier concepts following World War II. In the aftermath of the greatest conflict in history, the Navy found that it had worked itself out of a job in a postwar world where America had a monopoly on atomic weapons and many in the newly created Air Force regarded the other services as anachronisms. Even as the Navy stressed the need for balanced forces and the importance of sea power in the postwar world, it struggled to develop its own nuclear capability. The Navys first guided missiles were being developed, while naval aviation contended with the introduction of jet aircraft to the fleet and the development of heavy attack aircraft capable of delivering atomic weapons, which proceeded in the face of Air Force opposition.

The Navy had plans for the construction of a new super carrier, the United States, that could operate jet aircraft large enough to carry the early atomic bombs, which were nearly as large as the weapons that had been dropped by B-29s on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Throughout the postwar unification struggle, planning for the United States had continued. With the approval of Congress and the White House, funds had been appropriated and the keel of the carrier was laid at Newport News, Virginia, on 18 April 1949. Five days later, while Navy Secretary John L. Sullivan was out of town, Louis A. Johnson, who had replaced James V. Forrestal as Secretary of Defense when he had to resign in March 1949 following a nervous breakdown resulting from overwork, ordered all work on the carrier halted, ostensibly for budgetary reasons. Admiral Louis E. Denfield, the Chief of Naval Operations, learned of the action from a press release and Sullivan resigned in protest. He was replaced as Secretary of the Navy by Francis P. Matthews, who had no experience or appreciation of the Navy, let alone naval aviation. (Matthews was often referred to with scorn as Rowboat Matthews by senior naval leaders.) Naval leadership was in a state of shock, and regarded Johnsons actions as part of an Air Force campaign to retain its monopoly on nuclear warfare. These views seemed credible when funds allegedly saved by canceling the

Next page