A Presidio Press Book

Published by The Random House Publishing Group

This edition printed 1996

Copyright 1995 by William H. McRaven

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Presidio Press, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Presidio Press and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

www.presidiopress.com

Library of Congress-in-Publication Data

McRaven, William H. (William Harry), 1955

Spec ops: case studies in special operations warfare theory & practice / William H. McRaven.

p. cm.

Originally published under title : The theory of special operations.

eISBN: 978-0-307-54723-1

1. Special operations (Military science), Case studies. I. McRaven, William H. (William Harry), 1955-Theory of special operations. II. Title. U262.M37 1995

356.16dc20 94-46452

v3.1

Contents

Chapter 1

The Theory of Special Operations

Chapter 2

The German Attack on Eben Emael, 10 May 1940

Chapter 3

The Italian Manned Torpedo Attack at Alexandria, 19 December 1941

Chapter 4

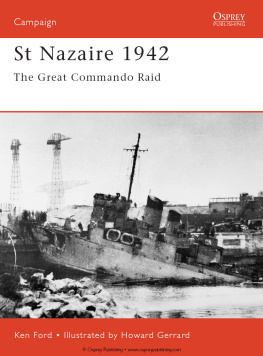

Operation Chariot: The British Raid on Saint-Nazaire, 2728 March 1942

Chapter 5

Operation Oak: The Rescue of Benito Mussolini, 12 September 1943

Chapter 6

Operation Source: Midget Submarine Attack on the Tirpitz, 22 September 1943

Chapter 7

The U.S. Ranger Raid on Cabanatuan, 30 January 1945

Chapter 8

Operation Kingpin: The U.S. Army Raid on Son Tay, 21 November 1970

Chapter 9

Operation Jonathan: The Israeli Raid on Entebbe, 4 July 1976

Chapter 10

Conclusions

1

Theory of Special Operations

In the realm of military literature, there is much written on theory of war, ranging from Herman Kahns thinking about the unthinkable on the nuclear end of the spectrum to B. H. Liddell Harts indirect warfare on the conventional end. There are theories of war escalation and war termination, theories of revolution and counterrevolution, and theories of insurgency and counterinsurgency. There are general airpower and sea power theories, and more specific theories on strategic bombing and amphibious warfare. Nowhere, however, is there a theory of special operations.

Why is a theory of special operations important? A successful special operation defies conventional wisdom by using a small force to defeat a much larger or well-entrenched opponent. This book develops a theory of special operations that explains why this phenomenon occurs. I will show that through the use of certain principles of warfare a special operations force can reduce what Carl von Clausewitz calls the frictions of war to a manageable level. By minimizing these frictions the special operations force can achieve relative superiority over the enemy. Once relative superiority is achieved, the attacking force is no longer at a disadvantage and has the initiative to exploit the enemys weaknesses and secure victory. Although gaining relative superiority doesnt guarantee success, it is necessary for success. If we can determine, prior to an operation, the best way to achieve relative superiority, then we can tailor special operations planning and preparation to improve our chances of victory. This theory will not make the reader a better diver, flyer, or jumper, but it will provide an intellectual framework for thinking about special operations. The relative superiority graph that will be shown later is a tool to assess the viability of a proposed special operation.

THE SCOPE OF THIS STUDY

To develop a theory of special operations I had to first limit the scope of the problem. This required developing the following refined definition of a special operation: A special operation is conducted by forces specially trained, equipped, and supported for a specific target whose destruction, elimination, or rescue (in the case of hostages), is a political or military imperative.

My definition is not consistent with official joint doctrine which broadly defines special operations to include psychological operations, civil affairs, and reconnaissance. The eight combat operations I analyzed to determine the principles of special operations and to develop the theory are more closely aligned to what Joint Pub 305 defines as a direct-action mission.however, the eight special operations that I analyze in this book were always of a strategic or operational nature and had the advantage of virtually unlimited resources and national-level intelligence. The refined definition also implies that special operations can be conducted by non-special operations personnel, such as those airmen who conducted James Doolittles raid on Tokyo or the submariners involved in the raid on the German battleship Tirpitz. Although I believe the theory of special operations, as presented in this book, is applicable across the spectrum of special operations, as defined by Joint Pub 305, it was developed solely from the eight case studies presented in this work. All usage of the term special operations henceforth will adhere to this refined definition.

WHY ARE SPECIAL OPERATIONS UNIQUE?

All special operations are conducted against fortified positions, whether a particular position is a battleship surrounded by anti-torpedo nets (the British midget submarine raid on the German battleship Tirpitz), a mountain retreat guarded by Italian troops (Otto Skorzenys rescue of Benito Mussolini), a prisoner of war (POW) camp (the Ranger raid on Cabanatuan and the U.S. Special Forces raid on Son Tay), or a hijacked airliner (the German antiterrorist unit [GSG-9] hostage rescue in Mogadishu). These fortified positions reflect situations involving defensive warfare on the part of the enemy.

Carl von Clausewitz, in his book On War, noted, The defensive form of warfare is intrinsically stronger than the offense. [It] contributes resisting power, the ability to preserve and protect oneself. Thus, the defense generally has a negative aim, that of resisting the enemys will if we are to mount an offensive to impose our will, we must develop enough force to overcome the inherent superiority of the enemys defense.

No soldier would argue the benefit of superior numbers, but if they were the most important factor, how could 69 German commandos have defeated a Belgian force of 650 soldiers protected by the largest, most extensive fortress of its time, the fort at Eben Emael? How can a special operations force that has inferior numbers and the disadvantage of attacking the stronger form of warfare gain superiority over the enemy? To understand this paradox is to understand special operations.

RELATIVE SUPERIORITY

Relative superiority is a concept crucial to the theory of special operations. Simply stated, relative superiority is a condition that exists when an attacking force, generally smaller, gains a decisive advantage over a larger or well-defended enemy. The value of the concept of relative superiority lies in its ability to illustrate which positive forces influence the success of a mission and to show how the frictions of war affect the achievement of the goal. This section will define the three basic properties of relative superiority and describe how those properties are revealed in combat.