Contents

Guide

In memory of Douglas Herps and Warwick Thomson

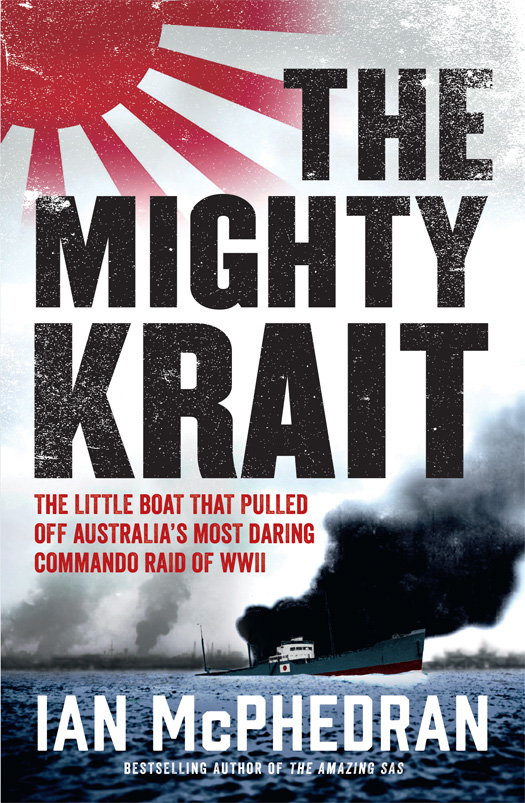

IAN McPHEDRAN is an award-winning bestselling author of six previous books. Until 2016, he was the National Defence writer for News Limited and during his extensive career as a journalist he covered conflicts in Myanmar, Somalia, Cambodia, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, East Timor, Afghanistan and Iraq. In 1993, he won a United Nations Association Peace Media Award and in 1999 the Walkley Award for Best News Report for his expos of the Navys Collins-class submarine fiasco. McPhedran lives in Balmain with his wife Verona Burgess.

The Smack Track

Afghanistan: Australias War

Too Bold to Die

Air Force

Soldiers Without Borders

The Amazing SAS

It was a warm summers day in 1969 when I first heard the remarkable story of a small wooden Japanese-built fishing vessel called the Krait and her role in one of the most audacious commando missions undertaken during World War II.

The late Australian war correspondent and author Ronald McKie, a friend of my father, Colin, gave me the job of mowing his large lawn on the side of Mount Gibraltar in my hometown of Bowral in the New South Wales Southern Highlands. When the mowing was done, he would treat me to a glass of lemonade in the cool of his study, whose walls were adorned with a collection of framed front pages showing his reports from the Asian and European theatres of World War II. McKie would also regale me with his adventures as a war correspondent, which to the eager ears of a 12-year-old boy were simply enthralling. They remain enthralling to this day.

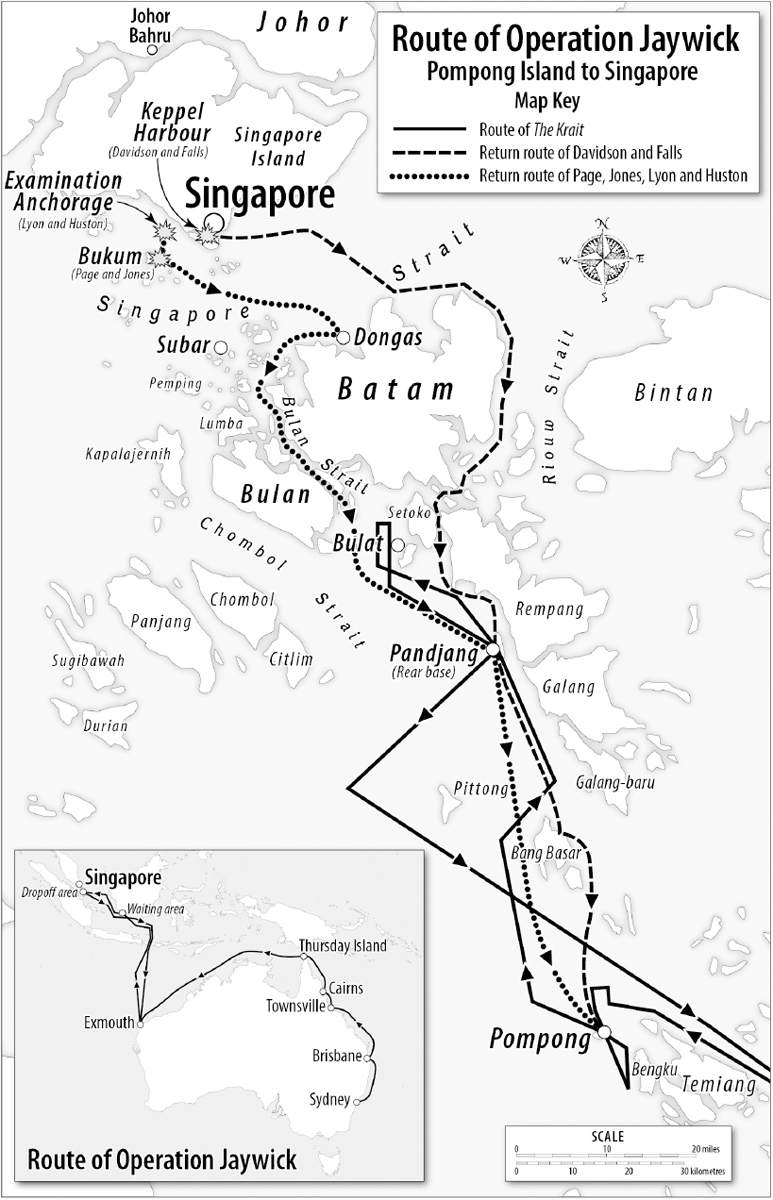

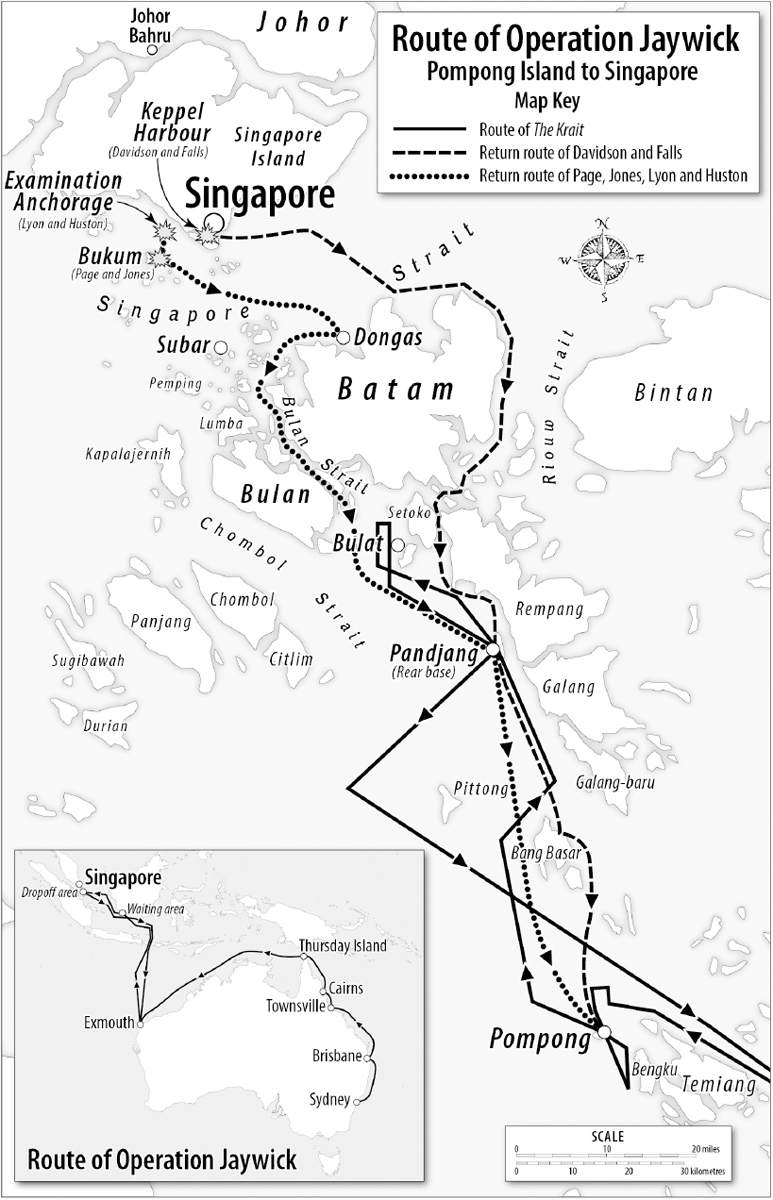

One of the most extraordinary tales, which he had turned into a bestselling book, The Heroes, published in 1960, was the story of Operation Jaywick. This was the codename for a successful attack against Japanese shipping in Singapore harbour on the night of 26 September 1943. A second, but disastrous, mission a year later was codenamed Operation Rimau.

The Jaywick raid is the stuff of legend among special forces. But outside those specialised circles, it is well known only to Australians of the surviving wartime and immediate postwar generations, and military aficionados.

Still less familiar is the story of the small, nondescript timber fishing boat that carried the 14 Allied commandos into the heart of enemy territory and delivered them safely back home.

That story continues to this day as the boat undergoes a new, careful renovation at the hands of expert shipwrights to bring her back to her 1943 configuration and to claim her rightful position as the symbolic flagship of Australian special forces operations.

September 2018 marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Kraits amazing journey, but there is much more to the story of the little boat that could.

Ian McPhedran

Sydney 2018

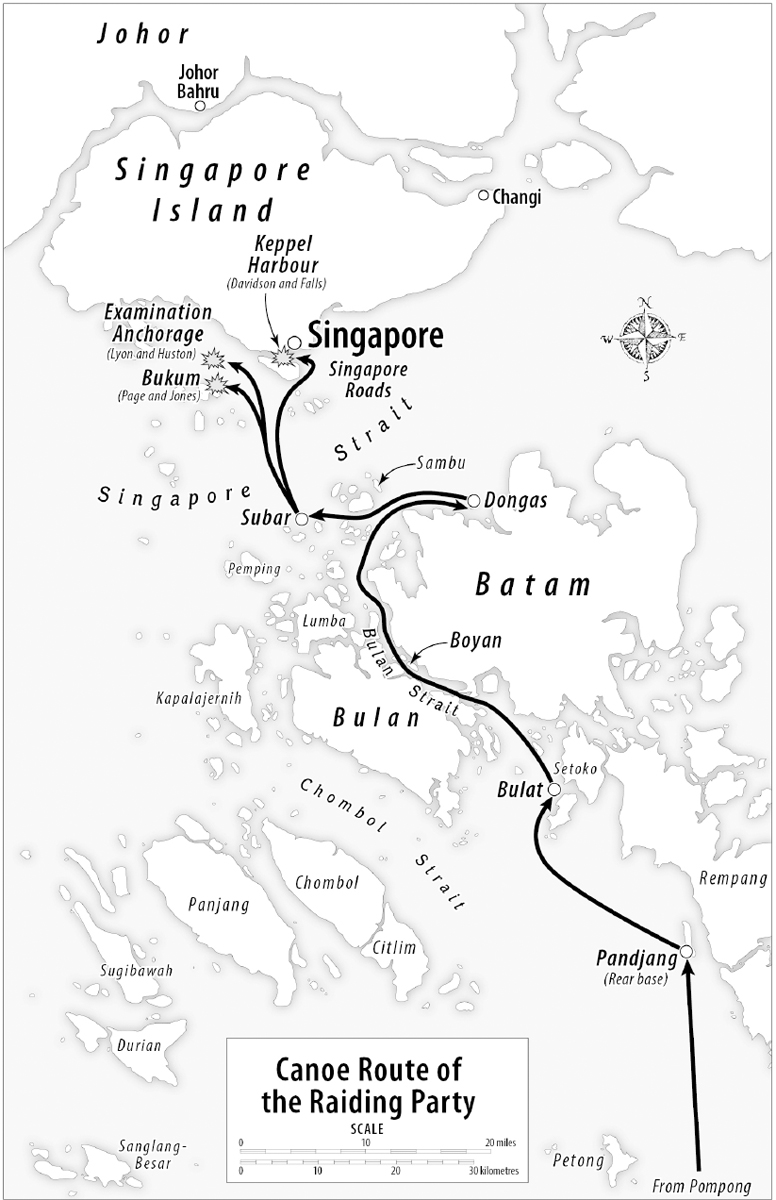

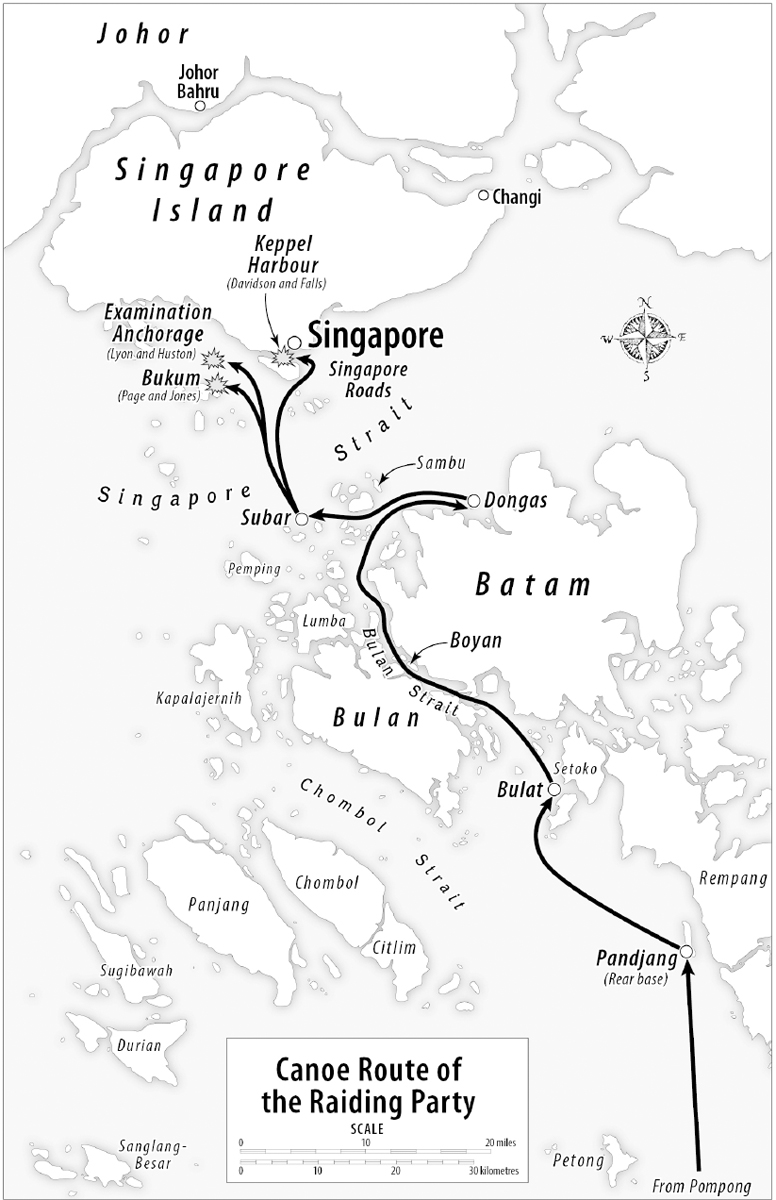

Late on the night of 26 September 1943, six young men with blackened faces paddling three canvas-covered, two-man folding canoes, slid silently into Singapore harbour at the sharp end of one of the most daring and successful special forces raids in the history of warfare.

As the lights of the occupied city blazed defiantly, none of the thousands of Japanese troops in the garrison, nor the hundreds of sailors on board the dozens of ships anchored in the harbour, could have imagined the cunning act of sabotage that was about to unfold.

Singapore in late 1943 was the impregnable heart of the rapidly expanding Japanese empire and a prison island for thousands of Australian and other Allied troops at the infamous Changi prisoner-of-war camp. Just like the British imperialists before him, the then Prime Minister of Japan, General Hideki Tojo, regarded the Japanese-occupied island as untouchable.

After attaching magnetic limpet mines to seven ships, the six raiders sneaked out of the harbour at the start of an arduous and exhausting 80-kilometre island-hopping return paddle, hoping and praying that they would be able to rendezvous with their mother ship, the MV Krait, for the long voyage home to Australia.

Reaching their first lying-up position on a tiny island off Singapore several hours later, four of the saboteurs climbed a hill from where they could see the brilliant lights. They watched and listened in awe as seven Japanese vessels either went to the bottom of the harbour or sustained serious damage from the mines they had attached below the waterline.

Mostyn Moss Berryman was a reserve canoeist who, instead of going on the raid, remained on board the Krait with seven shipmates while the vessel prowled around the islands and inlets of southern Borneo, hiding in plain sight disguised as a Japanese fishing boat and waiting to pick up the returning operatives.

Aged 95 and in 2018 the last survivor of Operation Jaywick, Berryman remembered the first time he laid eyes on the Krait as if it were yesterday.

The young navy volunteer and his mates had spent several weeks in training at the secret commando bush camp, known as Camp X, at Refuge Bay on the lower Hawkesbury River north of Sydney when, early one morning, a strange vessel motored into the bay. Berryman was taken aback by the sight of the ugly, squat, 21-metre timber boat. The keen 18-year-old sailor had expected to be posted to a nice big warship.

Seventy-five years later, at home in a retirement village in Adelaide, the clear-eyed, smartly dressed old gentleman recalled his commanding officer Captain Ivan Lyon ordering the team to paddle out and take a good look at the boat that would be their home for the next few months.

It looked Japanese, it was named Japanese and it smelled Japanese. It was a bit fishy, Berryman said. We climbed aboard and there was nothing there. She was as bare as a babys behind; no fridge, no bunks, no toilet, no nothing.

The men continued training hard and soon became experts at assembling special canvas-covered two-man folding canoes, or folboats, in double-quick time and paddling them over long distances in a variety of sea states. Around the camp fire at night they would speculate about what their top-secret mission could be and where this rickety-looking boat could possibly carry them. After some argy bargy the consensus was that the enemy-held port city of Rabaul on the island of New Britain in New Guinea was the most likely target.

We had read that there was a big harbour there, and there was going to be something to be blown up in Rabaul, Berryman recalled.

Not one of the young operatives imagined that the real target for their strange boat and her highly trained crew would be the enemy fortress of Singapore.

As it turned out, we broke the world record, Berryman said with justifiable pride. Nobody in the history of the world had ever gone that far into enemy territory and come out alive.

Millions of visitors to the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydneys Darling Harbour have strolled past the array of historic vessels on display in the water, but few might have noticed, let alone paid much attention to a black, low-slung, wooden ex-fishing vessel that was moored behind a locked gate for years.

Next page