CAROLYN TRANT

When I was an art student I often travelled from my home in London to paint landscapes in the Sussex Downs. It was like travelling back in time to Paradise the low sunlight on the hills resembled the tiny landscape backgrounds of the Gothic and early Renaissance paintings I had seen in museums and galleries. I painted in egg tempera, the medium of early religious art: pure ground pigment, usually coloured earths, mixed with eggyolk. In some of my earliest pictures I went so far as to paint an angel in a field or garden, but soon I found that this was unnecessary; it was the way this paint radiated from the bright, white gesso ground that gave the landscapes their special character. I was linked to artists removed in time and space by this association between paint, light and land. By choosing to work when the sun was low, I was conforming unwittingly to the hermetic vision of the Renaissance, in which nature and landscape were considered most permeated with sacred meaning at dawn and dusk when humans could touch the deepest rhythms of creation and achieve unity between their own spirit and that of the living universe (Cosgrove 1988:271). Piero della Francesca, Simone Martini, and Sassetta made their landscapes epiphanies of sacred moments.

This aspect of landscape presents a rich terrain of imaginative and symbolic thought that helps me to relate to the space and time in which I find myself. In this I agree with David Jones, one of a few twentieth-century painters interested in keeping alive a visual language of symbolic reference, a rich tradition in Europe that has roots in Classical, Celtic, Christian and Renaissance sources. Modernism broke with this tradition and now many people in England, including painters, look for their spiritual symbols in far away places the Far East, India, among North American Indians rather than mining the rich cultural seam in their own back gardens. This is because of a dislocation in our cultural chain. I think we need to look for ways of healing this break with our cultural past while retaining our modernist questioning spirit, and my way is to look at the shape and form and skin of the land itself, the result of mans past activity, history that was once a working present accretions of deposits, records of relocations, each stratum of civilization growing on the next, and like layers of tree rings, increasing with age.

The poet Kathleen Raine said of Jones, History was the space in which he lived. He could paint a tree, as in Vexilla Regis, with many explicit allusions to the Tree of Life, the Cross of Crucifixion, or the column of Roman imperial occupation. But much more simply, and to my mind more effectively, he could also make his historical references implicitly. His watercolour Rolands Tree, referring to the medieval Song of Roland, seems to suggest that the tree pictured might be the very one that Roland sat against. Now the actual tree happens to be an object existing in the material world of twentieth-century France, but historical fact does not matter here what is important is that Jones had to make this historical connection before he was able to find the inspiration to make a successful drawing. By bringing the past and present together in this way, Jones connects this living tree to all the trees that have ever been and invests it with a stature beyond time and space. This is what I interpret William Blake to mean when he wrote that paintings should be done from the imagination and not from nature.

This cumulative sense of here and now, linked to the past in a direct confrontation with the landscape is all-important to me. I like to work outside where there are plenty of physical and logistical problems to battle with. There is a tension between the inner and outer vision: what I know about a place affects my vision, at the same time as a stream of information through my eyes makes me reappraise what I know.

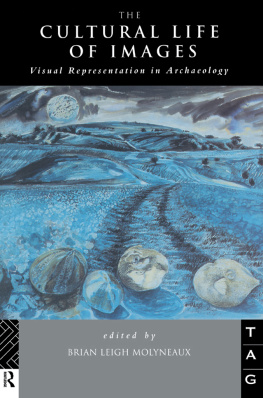

This relationship was difficult to achieve and express in images. When I completed my formal art training I moved into the heart of the countryside and made paintings that were a record, a diary, a catalogue of my immediate surroundings in all seasons, and of the livestock I now kept, vegetables I grew, and grass that I cut, spread and dried as hay. I knew every weed and patch of scrub that I fed to my goats. But after ten years and a summer spent by my pond minutely observing and recording the frogs emerging and submerging in the water plants, I realized I had gone too far. I identified with this land too much. When anyone disturbed a part of it in a way I felt was uncalled for cut down a hedge or a piece of grass it felt like a physical pain and I became unreasonably upset. Conversely, when the late afternoon sun shone on the tussocks of grass I wanted to roll in it and stuff it into my mouth in bliss. I painted a picture of a large bare field entitled All Flesh is Grass (a biblical quotation and the title of Brahmss German Requiem). I was surprised when people commented on the lack of content in the picture. I stopped painting and, eventually, moved back into town. My inactivity continued until I saw and applied for a commission advertised by South East Arts and the local County Council to study Earthworks on the Downs. The Downs in East Sussex represent a totally manmade and culturally defined landscape, from the sheep cropped turf and smooth deforested slopes to the palimpsest of chalk scars tracks, hillocks, flint mines and quarries that represent agricultural and protoindustrial activity. I saw the chance to record this dynamic landscape, as Artist in Residence on the Downs working for eighteen months between 1988 and 1990 to prepare an exhibition called Rituals and Relics, as a way to rework and clarify what I had been trying to communicate about our relation to the land in my earlier paintings.

An important aim of the project was to produce a body of work with wide public appeal not limited to the conventional art lover or confined to art galleries which would be shown in public places such as libraries and museums. I therefore decided to depict the Downs as we walk on them today, rather than producing imaginative illustrations of the sites and artifacts as they might have been when they were used. Archaeology gives us at best only a brief and partial impression of the past, and I was determined to record what was still with us in the land, rather than trying to imagine a past by creating reconstructions of events with people in exotic costumes. By working this way I would also question any preconceptions of landscape as a separate entity divorced from a working countryside and its people.

Since I had tried to live off the land as people in agricultural communities had done in the past I was sensitive to the intertwined physical/historical/social world we inhabit, as well as very conscious of the physicality of the land. I walked miles along the Downs every day making notes and drawings of anything I found interesting and then consulted the archaeological maps and records provided by the County Archaeologist. Sometimes I pored over the maps first, asking about the history of sites before looking for them to see if I wanted to draw them. The time of day was very important to me and it was when the sun was low that the pattern of the past under the skin was best revealed. For speed I abandoned egg tempera and drew with chalk pastels pure compressed pigment and charcoal, both elements of the earth which became the landscape again by an almost alchemical process of transformation.