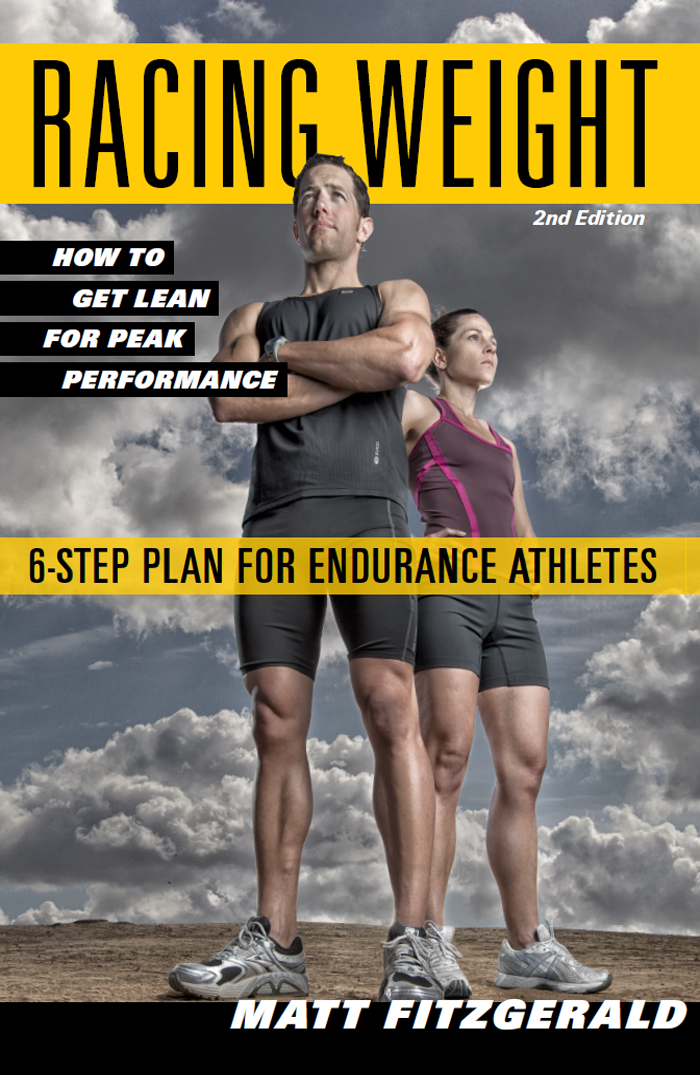

RACING WEIGHT

Copyright 2012 by Matt Fitzgerald

All rights reserved. Published in the United States of America by VeloPress, a division of Competitor Group, Inc.

Ironman is a registered trademark of World Triathlon Corporation.

3002 Sterling Circle, Suite 100

Boulder, Colorado 80301-2338 USA

(303) 440-0601 Fax (303) 444-6788 E-mail

Distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Publisher Services

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Fitzgerald, Matt.

Racing Weight: How to Get Lean for Peak Performance / Matt Fitzgerald.2nd ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-934030-99-8 (pbk.: alk. paper); ISBN 978-1-937716-26-4 (e-book)

1. Endurance sportsTraining. 2. Endurance sportsPhysiological aspects. 3. AthletesNutrition. 4. Body weightRegulation. I. Title.

GV749.5.F58 2012

613.2024796dc23

2012042138

For information on purchasing VeloPress books, please call (800) 811-4210, ext. 2138, or visit www.velopress.com.

Cover design by Maryl Swick

Cover photograph by Tim Mantoani

Interior photographs of Bishop, Kalmoe, Wellington, Cafaro, Bausch, Gould, Rowbury, and King courtesy of Corbis; Hall, Randall, Dombrowski, Flanagan, Haskins, and Kemper courtesy of Getty Images; Kostich courtesy of Ray Vidal; Jurek courtesy of Nick Onken; Olds courtesy of CJ Farquharson, CJFoto.com

Illustrations in and Appendix by Kagan McLeod and Mike Faille

Version 3.1

CONTENTS

TO THE SECOND EDITION

The premise of this book is simple: Weight management is as important for endurance athletes as it is for nonathletes, yet the goal and the best methods of weight management are different for those who race than they are for those who dont.

As a sports nutritionist and journalist I have written a great deal about weight management for both athletes and nonathletes. I must confess that I find it more rewarding to coach athletes toward getting leaner. The secret to weight loss for the overweight nonathlete is motivation. Most people who are really motivated to lose weight are bound to succeed. As they say, Where theres a will, theres a way. Dieters seldom fail for lack of knowledge. As a weight-management coach of nonathletes, I can only educate; the motivation to succeed has to come from within each individual. If that were easy, obesity wouldnt be so prevalent today.

Endurance athletes are different. The motivation to perform better is intrinsic to members of this group. Cyclists, Nordic skiers, rowers, runners, swimmers, and triathletes are willing to do what it takes to improve, whether its train harder, take recovery more seriously, work on their mental gameor lose excess body fat.

After the first edition of Racing Weight was published in November 2009, I started to receive feedback from athletes who had read it and had implemented the program. It has been gratifying to see the great number of positive results. Most of the athletes who have shared their success stories with me have thanked me for having addressed the longstanding need for a weight-management program designed especially for endurance athletes. I am always quick to point out to these folks that it is they who deserve the credit for their results. Yes, I have provided some useful information, but the motivation is theirs, and it makes all the difference.

There are other sorts of feedback that I have received from Racing Weight readers as well: questions, points of confusion, a few criticisms, and a correction or two. The book was not perfect. And any program that is based on the best practices of elite athletes and is supported by current science will begin to show its age as best practices evolve and science advances. Its not as if the most successful endurance athletes have started doing anything radically new for weight management or as if the scientific underpinnings of the Racing Weight program have been completely inverted, but over time we reshape these ideas in subtle but important ways.

For example, a colleague of mine, Robert Portman, PhD, who is one of the worlds leading sports nutrition researchers, recently made a compelling case in favor of concentrating carbohydrate intake in the early part of the day and protein intake late in the day. A small but growing number of athletes are now practicing this method with good results. Therefore I have chosen to incorporate it into the nutrient timing step of the Racing Weight system.

Quite apart from the evolution of athletic best practices and science, my thinking on training, nutrition, and weight management has continued to evolve through my experience as an athlete and coach. Where necessary, I have refined some of the tools presented in Racing Weight. The second edition of the book has been a welcome opportunity to address the questions and suggestions of the first editions readers, to update the program with the latest research, and to make the changes and additions that would make the program even more effective for motivated athletes.

The biggest change is that, whereas the original Racing Weight program comprised five steps, the revised program adds a sixth step: self-monitoring. Research has shown that self-monitoring practices and the behavioral modifications that surround them are the strongest predictors of successful long-term weight-loss maintenance in the general population. In this regard, endurance athletes are not so different from non-athletes. Readers of the first edition will recall that the book contained a chapter titled Monitoring Your Progress. However, the monitoring practices described therein were extrinsic to the program. By integrating self-monitoring into the Racing Weight method, you will, I hope, be able to tap this advantage in your effort to reach your racing weight.

Readers familiar with the first edition will notice other changes. I added , The Racing Weight Journey, provides additional guidance on how to put into practice the six steps of the Racing Weight program.

Less conspicuous but no less important than these structural changes are some new tools that have been added to the chapters that outline the six steps. These tools are intended to make the program as simple and easy to practice as it can possibly be.

MATT FITZGERALD

H ow would your performance change if you were at your optimal body weight? Imagine what it would feel like to set out on a run weighing 10 pounds less than you do right now. How much would it affect your efficiency, your endurance, or, more simply, your self-image? When was the last time you saw a marked improvement in your fitness? Do a few extra pounds stand between you and a faster race? Chances are that it was your quest for optimal body weight that led you to pick up Racing Weight.

You are not alone in this quest. Several years ago I assisted exercise scientists from Montana State University in conducting a survey of endurance athletes concerning their attitudes about their body weight and their weight-management practices. More than three thousand cyclists, runners, triathletes, and other endurance athletes responded. Most were serious competitive athletes who trained at least one hour a day, five days a week. The results of the survey, which were presented at a meeting of the Society for Behavioral Medicine in Montreal, Canada and published in the

Next page