BEING NUMEROUS

20 | 21

WALTER BENN MICHAELS, Series Editor

From Guilt to Shame by Ruth Leys

William Faulkner: An Economy of Complex Words by Richard Godden

American Hungers: The Problem of Poverty in U.S. Literature, 18401945 by Gavin Jones

A Pinnacle of Feeling: American Literature and Presidential Government by Sean McCann

Postmodern Belief: American Literature and Religion since 1960 by Amy Hungerford

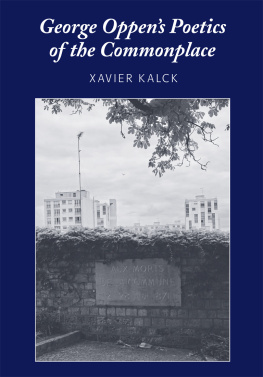

Being Numerous: Poetry and the Ground of Social Life by Oren Izenberg

BEING NUMEROUS

Poetry and the

Ground of Social Life

Oren Izenberg

Copyright 2011 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Cover art: Jason Salavon, The Grand Unification Theory (Part Three: Every Second of Its a Wonderful Life). Detail on front and on back.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Izenberg, Oren.

Being numerous: poetry and the ground of social life / Oren

Izenberg.

p. cm. (20/21)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-14483-2 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-691-14866-3 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Poetry, modern20th centuryHistory and criticismTheory, etc. I. Title.

PN1271.I94 2010 |

809.104dc22 | 2010020738 |

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Helvetica Neue

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe my first debt of gratitude to my parents. My father, Gerald Izenberg, showed me by his example how to lead a life of the mind while being fully present to others. My mother, Ziva Izenberg, has always instructed me with her powerful good sense and her unshakable will. They are the most generous people I know. Together, they have encouraged and supported everything I have set out to do; this book is dedicated to them.

I went to the Johns Hopkins University to study with Allen Grossman, a decision that was rewarded beyond all expectation. For many years, in Baltimore, Lexington, and Chicago, Allens immense learning and deep humanityalong with his powerful conviction that the work of poetry is intimately related to the work of being a person in the worldhave shaped my sense of what it is to be a scholar and a teacher. His inimitable voice is in my ear when I read poems and when I write about themmay it always be so. If Allen was this works first audience, Walter Benn Michaels was its second. Long afternoons spent working these ideas out in the pitched battle that is apparently his native idiom make up some of my best and most vivid memories of Hopkins. In recent years, Walter has been as generous in his friendship as he is merciless in argument; I am grateful for both.

Others have left their mark as well. Sharon Cameron showed me an unsparing intensity of attention to poems that I can only hope to approximate. John Guillory and Frances Ferguson, first as teachers and then later as colleagues, showed me how to follow an idea to its root. My fellow graduate students from those days formed an intellectual community thatthough now flung farcontinues to instruct and inspire me. Some of themin particular, Scott Black, Abigail Cheever, Daniel Denecke, Andrew Franta, Joanna Klink, Larissa MacFarquhar, Stacey Margolis, Dan McGee, Deak Nabers, Michael Szalay, Jane Thrailkillwill find that sentences they have spoken to me have made their way into this book.

At Harvard University, I was fortunate to be a part of a tremendous cohort of young faculty. My fellow Garden Level residentsLynn Festa, Yunte Huang, John Picker, Leah Price, Sharmila Sen, Ann Wierda Rowlandmade my time in Cambridge a happy one. Many other Harvard colleagues contributed to this book as wellspecial thanks to Forrest Gander, Jorie Graham, Barbara Johnson, Robert Kiely, and Peter Sacks.

Being Numerous was completed at the University of Chicago. There, Robert von Hallberg, by sheer force of personality and passionate devotion to literature and scholarship, createdfor a timea truly remarkable place to think and talk about poems. I am grateful to him, and to the rest of the faculty in the Program in Poetry and PoeticsDanielle Allen, Kelly Austin, Robert Bird, Bradin Cormack, Alison James, Liesl Olson, Mark Payne, Chicu Reddy, Jennifer Scappettone, Richard Strier, David Wrayfor years of conversation about my work and theirs. Other Chicago colleagues have been generous friends and interlocutors; particular thanks go to Lauren Berlant, Suzanne Buffam, Sandra Macpherson, and Eric Slauter for personal and intellectual companionship. Jim Chandler and Franoise Meltzer made the Franke Institute for the Humanitieswhich generously supported part of a years leavean intellectually lively and productive place to be. I have also been tremendously fortunate in my students at Chicago. Joshua Kotin, Jenny Ludwig, Marta Napiorkowska, Kiki Petrosino, Andrew Rippeon, Michael Robbins, Dustin Simpson, and Michelle Taransky helped me to think through many of the arguments in this book in a memorable (to me) seminar on Radical Poetics. Throughout my years at the University, they, along with V. Joshua Adams, Stephanie Anderson, Joel Callahan, Michael Hansen, Billy Junker, Chalcey Wilding, and Johanna Winant have continued to teach me with their love for poems and for ideas.

Good conversation about poetry transcends the narrow confines of institution and discipline. Charles Altieri, Brett Bourbon, Steve Burt, Jeff Dolven, Roland Greene, Lyn Hejinian, Susan Howe, Sean McCann, Maureen McLane, Sianne Ngai, Marjorie Perloff, Ron Silliman, and Barrett Watten have all challenged me to think harderthrough their writing, in their questioning, and sometimes by their opposition. Mark Canuel and the English Department at the University of Illinois at Chicago have provided an intellectual haven. Jennifer Ashton deserves special acknowledgment. She has read many of these pages many times, and I am thankful for her critical intelligence and for her steady friendship.

Audiences at Brown University, Williams College, and the Johns Hopkins University provided helpful responses to work in progress. Earlier versions of some of these chapters have appeared in several journals: thanks to the editors of Critical Inquiry, Modernism/Modernity, and Modern Philology for allowing me permission to reprint from them here. Thanks to Hanne Winarsky at Princeton University Press for believing in this book and shepherding it through to publication; to two anonymous readers for their insightful commentary and criticism; and to Ellen Foos and Jodi Beder for their exhaustive work on the manuscript. After their careful attention, any mistakes that remain are my own.

Above all, I am thankful to Sonya Rasminsky. Her intelligence, judgment, and nearly infinite patience have made this work possible. Her love and friendship make everything else possible. These pages are about the burdens and obligations of being a person. Sonya, together with our children, Toby and Miri, have taught me the joys.

INTRODUCTION

Poems, Poetry, Personhood

It is time to explain myself. Let us stand up.

Next page