For Setsuko

Look East, where whole new thousands are!

R OBERT B ROWNING , W ARING

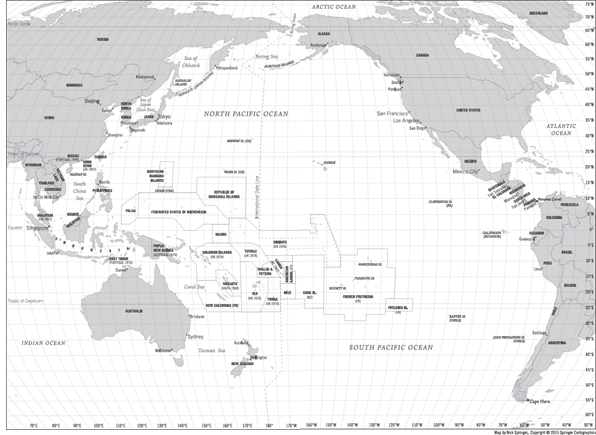

Nick Springer/Springer Cartographics LLC.

CONTENTS

Guide

Here from this mountain shore, headland beyond stormy headland plunging like dolphins through the blue sea-smoke

Into pale sealook west at the hill of water: it is half the planet...

arched over to Asia, Australia and white Antarctica: those are the eyelids that never close; this is the staring unsleeping

Eye of the earth; and what it watches is not our wars.

R OBINSON J EFFERS, FROM T HE E YE, 1965

United Airlines Flight 154 leaves Honolulu International Airport just after dawn three times a week, bound ultimately for the city of Hagta, the capital of the island republic of Guam. If the northeast trades are blowing at their usual steady twelve knots, the jet will take off to the east, into the low morning sun over Waikiki, and those passengers on the aircrafts left side will see the wall of skyscraper hotels along the beachfront and be able to glimpse down at Doris Dukes great seaside mansion, Shangri-La. Once the plane is two miles high above the crater of the dormant Diamond Head volcano, it will begin to make a long and lazy turn to the right.

If the morning haze is light, passengers on the right side now can sometimes glimpse the bombers and heavy transport planes lined up on the flight line of Hickam Field, and maybe a flotilla of sleek gray warships will be gliding slowly through the lochs of Pearl Harbor. There will be some suburbs clustered between the shore and the slopes; there will be a skein of rush-hour traffic crawling along on H-1, the main thruway into Honolulu; and behind these urban images will rise ranges of mountains, razor-sharp aiguilles dotted in places with white radar domes.

With every one of its seats invariably filled, the plane will then clear its throat and tilt its nose ever higher, and once at five miles high, it will set its autopilot to a southwesterly course, heading out initially over two thousand miles of clear blue, unpeopled ocean. As the climb flattens out, and the aircraft passes through a final stratum of small puffballs of cloud, in a blink the island behind fades, is suddenly gone from view, and all below is just sea, endless empty sea, with many hours of emptiness ahead.

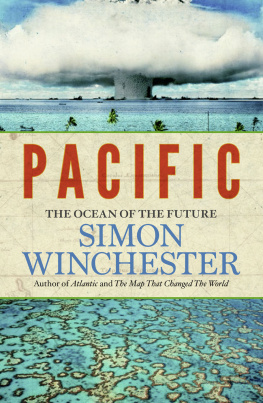

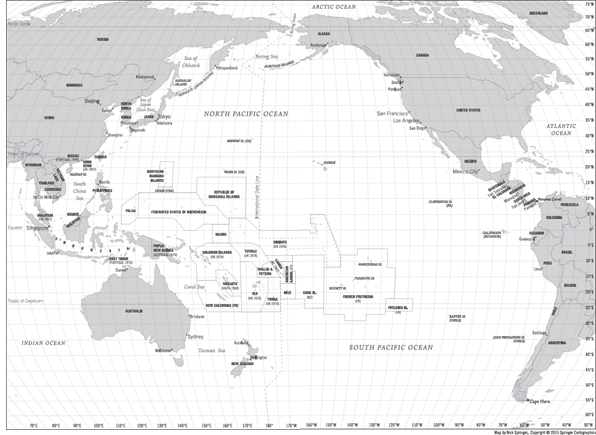

The ocean beneath is almost unimaginably vast, and illimitably various. It is the oldest of the worlds seas, the relic of the once all-encompassing Panthalassic Ocean that opened up seven hundred fifty million years ago. It is by far the worlds biggest body of waterall the continents could be contained within its borders, and there would be ample room to spare. It is the most biologically diverse, the most seismically active; it sports the planets greatest mountains and deepest trenches; its chemistry influences the world; and the planetary weather systems are born within its boundaries.

Most see this great body of sea only in partsa beach here, an atoll there, a long expanse of deep water in between. Just a few, mariners mostly, have the good fortune to confront the ocean in its entiretyand by doing so, to win some understanding of the immense spectrum of happenings and behaviors and people and geographies and biologies that are to be found within and on the fringes of its sixty-four million square miles. For those who do, the experience can be profoundly humbling.

Captain Cook wrote that by exploring the Pacific he had gone as far as I think it is possible for man to go. To traverse it today, two and a half centuries laterto set a course from Kamchatka to Cape Horn, to pass between the Aleutians and Australia, to make a ten-thousand-mile crossing from Panama to Palawanis to experience a sense of the frontier that is lacking almost everywhere else on the planet. And not simply for its immensity, but also for the pervasive sense, even today, of confrontation with the unknown and the unknowable. The British Admiraltys revered chartroom bible, Ocean Passages for the World, still cautions sailors embarking on a crossing, Very large areas of the Pacific Ocean are unsurveyed, or imperfectly so. In many areas no sounding at all has been recorded... the only safeguards are a good lookout, and careful sounding.

United 154, operated most days by one of the more battered old planes from Uniteds Hawaiian stable, is known locally as the island hopper, makes its journey along almost six thousand miles, and takes some fourteen shuddering hours to do so. It skitters southwestward, then westward, then northward, stopping along the way at five placesall of them islands, scattered among three different countriesthat are even less familiar to most than is Guams one city of Hagta.

UA154s first stops, of half an hour or so, are on the flat atolls of Majuro and Kwajalein in the Republic of the Marshall Islands; it then does the same at runways that have been squeezed into the more dramatically mountainous and jungle-draped topographies of the islands of Kosrae, Pohnpei, and Chuuk, in the Federated States of Micronesia.

A scant few passengers travel all the way to Guam. There is much getting off and getting on, and luggage of daunting sizes and bewildering shapes is brought on and taken off at each stop. The crew members, leather-skinned old-timers who have some passing acquaintance with the local island languages, are obliged by United to make the entire journey. They will have recited their seat-belt and tray-table hymns no fewer than twelve times before final touchdown, and seem almost comatose with relief on their arrival in Guam.

In the popular European imagination, the Pacific Ocean contains many of the elements that are to be found along that six-thousand-mile passage between Honolulu and Hagta. In every stopping place, it is invariably warm, tropical; both the sea and the sky are intensely blue, the air is sweetly breezy, and there are white sands and coral reefs and sparkling fish of vivid colors darting between the anemone fronds. The roads are decked with bougainvillea and flamboyants and orchids and parrots, with papaya trees and palms of incredible profligacy that drip with dates and bananas and coconuts. Palm trees are central to Pacific imagery: they are to be seen leaning slightly off the vertical, under the endless press of the trade winds, and thereby offering a picture-perfect and theatrically green backdrop for every beach scene; a frame for other equally familiar images of curling waves and spume; or as a border to an empty ocean panorama with its distant gatherings of surfers waiting patiently for the rollers to break and the seas to begin to run.

Such is in evidence everywhere, at every stop, on the United island hoppers run. Hawaii, the starting point, is of course the quintessential exemplar of the mixing of what outsiders see as Polynesian magic and transpacific migration. From Polynesia there is the plangent sound of the ukulele, the sight of the grass skirt, the blossom in thick black hair tipped behind the ear, the nut-brown skin, the dancing, the dancing, the dancing.

Yet when I lived for a while in Manoa, on the eastern side of Honolulu City, it was not so much Polynesian culture that lapped into every corner of my life as the cultural influences of the farther side of the Pacific Ocean. There was a Japanese grocery store down the street, a Burmese restaurant next door, and every other person on the bus seemed to be from Manila. I kept hearing Korean spoken in the elevators, and met Chinese migrants in the most unexpected places: the elderly man who cut what remains of my hair was from Kowloon, and had been a waiter for decades on the