Late one warm summer night in 2007, Mike drove from the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, to our home in a village outside the city and turned on the computer. His task was to tell friends and family the good news that Dimitra had just given birth to twins, and that all three of them were doing fine. When he opened his email, there was a new message from Thames & Hudson. It seemed that our Neanderthal book proposal had been accepted. The question was, with newborn twins, how could we now find time to write it?

We had no way of knowing it then, but this was a lucky coincidence. Had we met the original September 2008 contractual deadline, the book would have been immediately obsolete. The pace of new discoveries has been staggering. For example, when we started writing on the human colonization of Europe, the accepted time of arrival was 800,000 years ago. By the time we had finished the first draft some weeks later, it was 1.2 million years ago. In another case, a new discovery in Kenya set a new age record for handaxe tool technology at 1.76 million years ago. It was not just new discoveries, but the development of new technologies that brought about the greatest changes.

The most startling news came in 2010, by which point we had put the writing on hold in order to move the family across the ocean to America. (Wed like to think that this makes the book the ultimate Thames & Hudson publication, because we started it close to one river and finished it a few miles from the other.) Had we submitted the book before this announcement, we would have missed out on a crucial line of evidence from the emerging field of palaeogenetics.

The idea for this book dates back much earlier, some twenty years before the current golden age of discovery, to our student days. Dimitra, who once excavated royal Roman tombs in Cyprus, explained why she spent so much time studying stone tools from 100,000 years ago, when the Earth still held untold secrets hidden cities buried by desert sands, Egyptian tombs, cave paintings. She said that her work was the most interesting of all, for ultimately she was exploring what it means to be human. Mike, who studied archaeology as a historian of science, slowly became drawn in to this field, which goes by the misleadingly boring name of Middle Palaeolithic archaeology. Eventually we felt that we could combine our skills to write something that neither of us could do alone. Dimitra remains the real archaeologist in this endeavour, while Mike helped to shape the narrative.

Dimitras connection to the Neanderthals goes back much earlier. In we discuss the Neanderthal site of Kokkinopilos in Greece, and a Nazi guard post that stands atop it. The historian Mark Mazower mentions the survival of such guard posts in his book Inside Hitlers Greece (1993), where he also describes a massacre by the Nazis in the nearby village of Kouklesi, carried out in revenge for an attack by the resistance. One of the victims of this massacre was a teenage boy named Dimitrios, who was not in the resistance but who had the bad luck to be caught wearing a shirt that was made in Britain, casting suspicion on him.

Years later, Dimitrioss brother, Anastasios, was asked by friends in the nearby village of Rizovouni to become godfather to their newborn daughter. Anastasios agreed, and according to tradition was able to name the child. He named her after his murdered brother, choosing the female version of the name. Dimitra later became involved with a Cambridge project in the region and ended up writing her PhD dissertation on the stone tools of Kokkinopilos a short distance from her village and other redbed sites in the region.

The greatest lesson we have learned from studying the Neanderthals is not to demean them. When we tell friends about this project, they often say something sarcastic like, I know a few Neanderthals you might include in the book. Well only know we succeeded if people start to show the Neanderthals some deserved respect. They were accomplished humans, too. Plus, its cowardly. If you had made fun of them directly to their chinless faces, they might have torn your arms off.

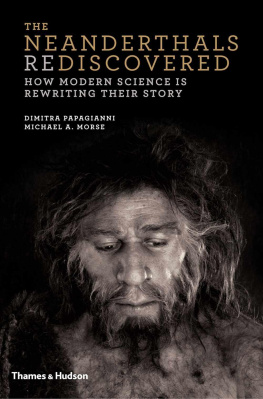

Our main motivation for writing this book, however, has been our conviction that the Neanderthal story is a compelling one one that has not previously been told in its entire dramatic arc from origins to expansion to demise. Most books with the word Neanderthal in the title seem to collapse the species into an ahistorical list of features and important sites before morphing into a book on the species that replaced them. We wanted to write a book on the Neanderthals that does not dwell too much on the false turns in the long history of research and does not get easily distracted by the entry of Homo sapiens on to the scene. In short, we envisioned a book on the Neanderthals that is fairly exclusively about the Neanderthals.

The need for a book like this became apparent when Dimitra started teaching a course called The Neanderthal World in various university continuing education programmes. Her course was unusual in that it looked at human evolution from the Neanderthal point of view, and she discovered that it was immensely popular. Students kept asking her to recommend a book, and she realized there was no good single source on the Neanderthals. The most comprehensive book was In Search of the Neanderthals by Chris Stringer and Clive Gamble. Published back in 1993, this was becoming out of date and did not have anything on the exciting new discoveries. While there are many good books to recommend that touch on the topic, we wanted to bring all the threads of the Neanderthal story together in one place.

We think the rise and fall of the Neanderthals is one of the greatest stories from the prehistoric past. After more than 150 years of archaeological discovery, the Neanderthals are the best-known human species other than ourselves. They are the one most closely related to us. And they coexisted with us quite recently: for the last Neanderthals, who may have died off around 30,000 years ago, the earliest modern human art in Europe was quite ancient, perhaps thousands of years old by then. For all these reasons, we had long wanted to share our fascination with them. It was just a matter of timing. And given how much more we know now than we knew when we started this journey, we hope youll agree that the best time is, in fact, now.

It is impossible to write about a million years of prehistory, including sites from western Europe to central Asia, and about fields as disparate as biological anthropology, genetics, geology and archaeology, without tremendous help. We are indebted to our many friends and colleagues who have helped guide our thinking. This book could not have been written without them. At the same time, we have presented the Neanderthal story through the filter of our own idiosyncratic choices, and responsibility for those, and indeed any mistakes, is ours alone.

We would particularly like to thank Mircea Anghelinu, Nick Ashton, Jill Cook, Clive Gamble, Ivor Karavani, Mark Lamster, Paul Pettitt, Nellie Phoca-Cosmetatou, Matt Pope, Wil Roebroeks, Antonio Rosas, Katharine Scott, Chris Stringer, Aaron Stutz, Carolyn Szmidt and Carole Watkin.

Our editor, Colin Ridler at Thames & Hudson, played a very large role in shaping the book, and we owe him a huge debt of gratitude. Sincere thanks are also due to the rest of the team there: Kim Richardson, Louise Thomas, Sarah Vernon-Hunt, Aaron Hayden, Terry Martin, Celia Falconer and Steve Russell.

A key aspect of Neanderthal research is reconsidering what it means to be human. As we were delving into the human past to answer this question, we were also becoming intimately familiar with a different kind of human mind the autistic one within our own family. For teaching us the true essence of humanity and for being a constant source of joy, we dedicate this book to the boys who were born the same night that Thames & Hudson gave the project the green light, and to their sister who has become at least as enthusiastic about the Neanderthals as we are.

Next page