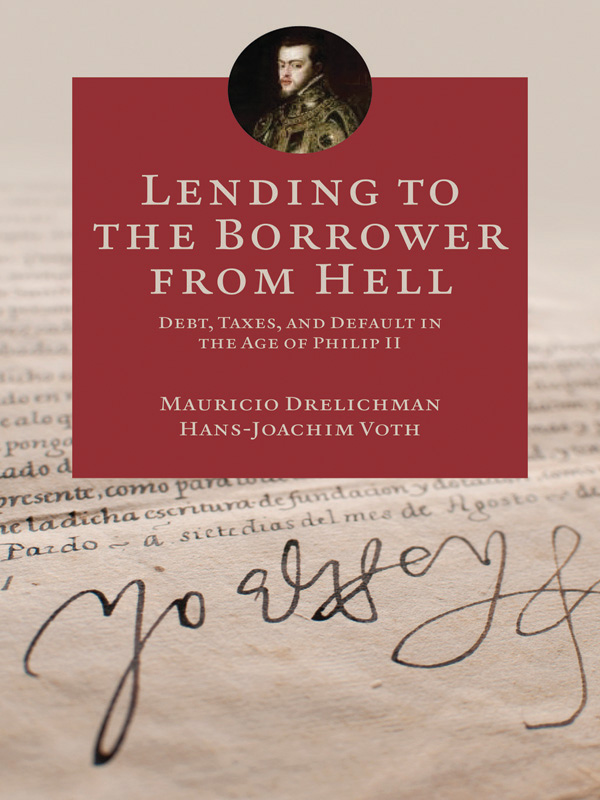

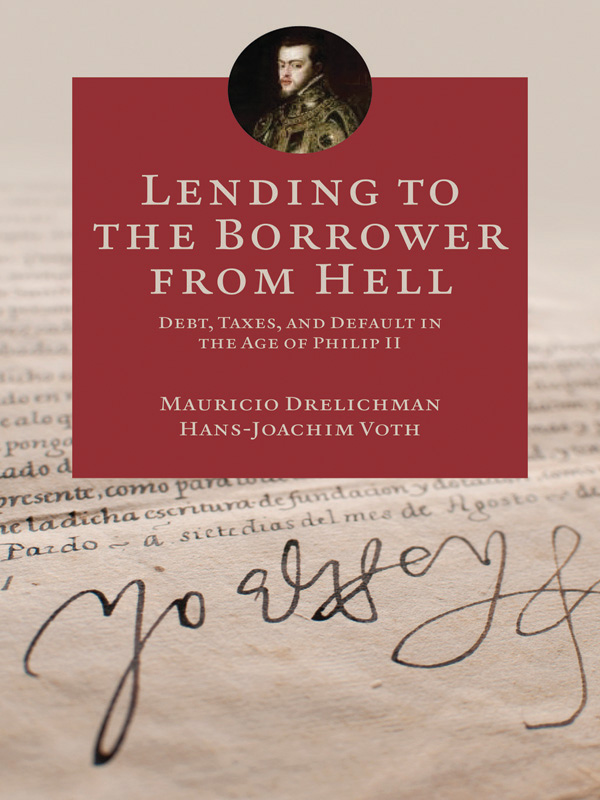

LENDING TO THE BORROWER FROM HELL

THE PRINCETON ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE WESTERN WORLD

JOEL MOKYR, SERIES EDITOR

A list of titles in this series appears at the end of the book

LENDING TO THE BORROWER FROM HELL

DEBT, TAXES, AND DEFAULT IN THE AGE OF PHILIP II

MAURICIO DRELICHMAN AND HANS-JOACHIM VOTH

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket photograph: Signature of Philip II, reading Yo, el Rey. Courtesy of the General

Archive of Simancas, Ministry of Culture, Spain, PTR, LEG 24, 22.

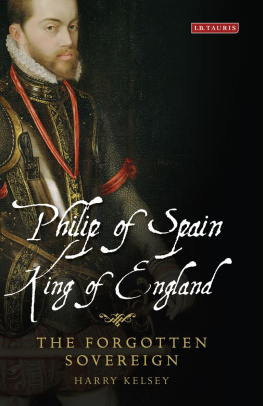

Jacket art: Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) (c.14881576), detail of King Philip II (152798), oil on canvas, 193 x 111 cms. 1550. Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain. Courtesy of Bridgeman Art Library, NY.

All Rights Reserved

Drelichman, Mauricio.

Lending to the borrower from hell : debt, taxes, and default in the age of Philip II / Mauricio Drelichman and Hans-Joachim Voth.

pages cm. (The Princeton economic history of the western world)

Summary: Why do lenders time and again loan money to sovereign borrowers who promptly go bankrupt? When can this type of lending work? As the United States and many European nations struggle with mountains of debt, historical precedents can offer valuable insights. Lending to the Borrower from Hell looks at one famous casethe debts and defaults of Philip II of Spain. Ruling over one of the largest and most powerful empires in history, King Philip defaulted four times. Yet he never lost access to capital markets and could borrow again within a year or two of each default. Exploring the shrewd reasoning of the lenders who continued to offer money, Mauricio Drelichman and Hans-Joachim Voth analyze the lessons from this important historical example. Using detailed new evidence collected from sixteenth-century archives, Drelichman and Voth examine the incentives and returns of lenders. They provide powerful evidence that in the right situations, lenders not only survive despite defaultsthey thrive. Drelichman and Voth also demonstrate that debt markets cope well, despite massive fluctuations in expenditure and revenue, when lending functions like insurance. The authors unearth unique sixteenth-century loan contracts that offered highly effective risk sharing between the king and his lenders, with payment obligations reduced in bad times. A fascinating story of finance and empire, Lending to the Borrower from Hell offers an intelligent model for keeping economies safe in times of sovereign debt crises and defaultsProvided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15149-6 (hardback)

1. Finance, PublicSpainHistory16th century.2. Debts, PublicSpainHistory16th century.3. TaxationSpainHistory16th century.4. Philip II, King of Spain, 1527

1598.I. Voth, Hans-Joachim.II. Title.

HJ1242.D74 2014

336.4609031dc232013027790

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Verdigris MVB Pro Text and Gentium Plus Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

TO PAULA

TO BEA

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Blame the Midwest. Tender academic minds often need peace and quiet to get down to business. We first met in the delightful town of La Crosse, Wisconsin (also known as Mud City, USA), where distractions were few and far between. This is the place that the organizers of the annual Cliometrics conference had chosen as a venue in 2003. The authors got talking and quickly agreed that they should look into a joint project on the early history of sovereign borrowing. Philip IIs defaults are justly famous, but had not been given their due from an economic perspective, or so we felt. Explaining why everyone before us had been wrong also seemed the best way to use two characteristic virtues of our respective nationalitiesmodesty, for the Argentine, and subtlety, for the German.

Money may be the sinews of power, but it is also the lifeblood of scholar-shipand especially so if the project involves extensive data collection in the archives, plus the coding of hundreds of contracts written by hand in sixteenth-century script. This book would not exist without the financial support of several institutions. We have been fortunate in receiving funding by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MICINN). Sadly, the annual treasure convoys from Madrid, laden with ducats earmarked for research and sailing, did not always arrive in full strength. Our applications almost floundered when we failed to specify whether the project required use of the Spanish research station in Antarctica, or if we would need an oceanographic research ship. The importance of linguistic accuracy was brought home to us when we discovered, minutes before submitting the research budget, that we were about to request cases of red wine (cajas de tinto) instead of ink-jet cartridges (cartuchos de tinta). Despite correcting this potentially embarrassing line item, our funding requests were often cut by 60 to 80 percent without explanation, even during Spains boom years, while receiving the highest marks for academic merit. We are grateful for the limited funds that did arrive; the firsthand insight into the intricacies of Castilian administration also helped us to understand the bureaucratic machine that takes center stage in this book.

With Spanish treasure in variable and occasionally short supply, we moved a good part of the project to the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver, where we hired a large share of the Spanish-speaking graduate student population to transcribe and code up our data. As a result, we are now more convinced than ever that the mita, the forced labor service invented by the Spanish colonizers to exploit the rich silver mines of Potos, had much to recommend it. In its absence, we are grateful that we could draw on generous funding by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, and the UBC Hampton Fund, which did not find it odd to provide an Argentine scholar with an American PhD working in Vancouver with funds to pay for Spanish-speaking research assistants so that we could code up data from Castile.

Young scholars often imagine research as a glamorous, thrilling activity, combining exciting, Dan-Brown-like moments of discovery in dusty archives with joyful international jet-setting. Of course, this image is all wrong. Neither the siren calls of the Whistler ski resort, hiking in the Rockies and the Serra de Tramuntana in Mallorca, boating in Vancouvers English Bay, nor long lunches by Barceloneta Beach distracted us from our labors (at least most of the time).

We should also mention our gratitude for the many discomforts endured on interminable flights between Barcelona and Vancouver (as well as various conference locations), courtesy of Lufthansa, Air Canada, and a variety of American carriers. Without being confined to a narrow steel tube, rebreathing the same stale air for twelve to fourteen hours at a time, accosted by strange smells, offered inedible food, and without the front passengers seat firmly wedged against our kneecaps, we would have found it much harder to concentrate on data analysis and the writing contained in this booka good part of which was completed high above the Atlantic and the Great Plains of North America.

Next page