Series Editor: Andrew F. Smith

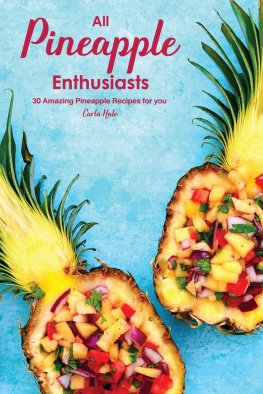

Pineapple

A Global History

Kaori OConnor

REAKTION BOOKS

For Phil Gusack

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2013

Copyright Kaori OConnor 2013

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China

by Toppan Printing Co. Ltd.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780232218

Contents

Introduction: Origins and Discovery

During his second voyage to the New World, Christopher Columbus came ashore on 4 November 1493 on the newly sighted Caribbean island he had just named Santa Maria de Guadeloupe, and promptly discovered the pineapple (Ananas comosus). The occasion was not the ceremonial presentation beloved of later artists of the Empire, like Francesco Bartolozzi, in which native chiefs came forward to offer the fruits and wealth of the land to foreign explorers. Instead, on landing the Europeans made for a settlement that could be seen from the beach, only to find it deserted, the Tupinamb people having fled to the hills in fear. In the abandoned huts they discovered many parrots with purple, red, green, blue and white feathers, and calabashes full of fruit that looked like green pine cones but were much larger, and were filled with solid pulp, like a melon, but were much sweeter in taste and smell. In addition to its taste, they were fascinated by the appearance of the fruit and its curious quilted surface, resulting from the fact that the pineapple is not one fruit but many. Each pineapple is composed of upwards of a hundred individual berries, fused together. Much later it would be realized that a pineapples skin is an example of a Fibonacci sequence, a pattern that draws the eyes and challenges the brain in a natural form of enchantment.

Despite these attractions, the pineapples first sighting was a disappointment, because the aim of the voyages of the great European age of exploration that spanned the period from the beginning of the fifteenth century to the start of the seventeenth century was to find riches in the form of gold, silver, pearls, spices and precious stones. The enduring legacy of these voyages would be enrichment of another kind the discovery of new foods like the pineapple that would change forever the way Europe and the rest of the world ate. However, this was far in the future.

Francesco Bartolozzi, An Indian Priest Addressing Columbus in the Island of Cuba, 1794, engraving. A pineapple is among the proffered fruits.

The Pyne Frute, drawing associated with John White, c. 158593. |

|

Taking seven parrots and some of the curious fruit, Columbus and his men returned to the ships and set sail for the great island of Hispaniola, where the Admiral had made landfall on his first voyage, and where he knew gold was to be found. This was a new world in every sense, challenging all that had been known before, and everything the voyagers saw evoked wonder and fear in equal measure. Strange animals and fantastical birds made their homes in a magical setting that seemed to know no seasons. The air was perfumed with what seemed to the men to be the smell of roses and other delicate but unknown blooms. Plants produced fruits and seeds throughout the year in great abundance apparently without human aid, and from the ships the luxuriant greenery seen on the shore gave the appearance of paradise gardens.

| Beauty and danger in the New World. Only the pineapple quickly overcame the colonists fear of native foods. Parrot with snake in its beak, French, late 17th century, watercolour. |

Columbus wrote in his journal that the beauty of what he saw tempted him to stay there forever, but soon more practical considerations arose. Provisions brought from Spain began to run short and the men had not yet learned what colonists notably snakes and iguana lizards. Only the pineapple appealed.

It was soon realized that the first fruits found on Guadeloupe had been of the small, wild sort, but there were larger cultivated pineapples that were even more delicious. Columbuss discovery of the plant was only the latest encounter in a chain that stretched deep into time and the Amazon heartland, where the pineapple is believed to have originated, along with the narcotic coca plant and the cacao tree, source of chocolate. The Tupinamb people ate pineapple fresh, roasted it over the fire, dried it and made wine from it. As well as using pineapple as a food and a drink, they employed it as a medicine, made fibres for netting and plaiting from the leaves, and used it to make poison for their arrowheads. By the time Columbus arrived in the New World, Native American activity over many centuries had spread the pineapple to present-day Brazil, Guiana, Colombia, parts of Central America and the West Indies. Because native methods of cultivation appeared haphazard and even invisible to Europeans, the skill the Native Americans had invested in developing different pineapple species was not appreciated. Instead, the pineapple was regarded by the newcomers as the gift of bounteous Nature, the benefaction of a divine providence.

![Annies - Doily afghans: [5 colorful afgans made using worsted-weight yarn!]](/uploads/posts/book/166053/thumbs/annie-s-doily-afghans-5-colorful-afgans-made.jpg)