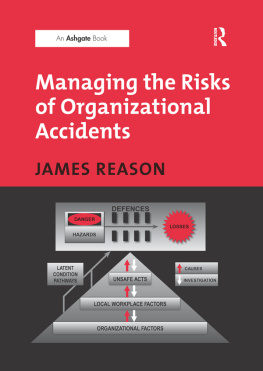

A LIFE IN ERROR

A Life in Error

From Little Slips to Big Disasters

JAMES REASON

Professor Emeritus, The University of Manchester, UK

ASHGATE

James Reason 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher.

James Reason has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

Published by

Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Wey Court East

Union Road

Farnham

Surrey, GU9 7PT

England

Ashgate Publishing Company

110 Cherry Street

Suite 3-1

Burlington, VT 054014405

USA

Ashgate Website: http://www.ashgate.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Reason, J.T.

A life in error: from little slips to big disasters / by James Reason.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4724-1841-8 (paperback)ISBN 978-1-4724-1842-5 (ebook) ISBN 978-1-4724-1843-2 (epub)

1. Industrial accidents. 2. Errors. I. Title.

HD7262R39 2013

153.4dc23

2013021078

ISBN 9781472418418 (pbk)

ISBN 9781472418425 (ebkPDF)

ISBN 9781472418432 (ebkePUB)

Contents

This book is like a personal and intimate trip through the ideas that pioneered human error and industrial safety. It goes into day-to-day experience of errors, contains testimonials and anecdotal information, and widens to system safety. Everything seems to have been said on the topic, and yet the book puts the matter differently in a manner that is true, full and in plain, jargon-free language. I love this book.

Ren Amalberti, Haute Autorit de Sant, France

Reasons new book is a master class on human error: a concise tour of his career explaining how mistakes can occur. It is a pleasure to accompany him while he presents his favourite and often funny accounts of fallibility, tempered with insights on the resulting risks and how they can be mitigated. Highly recommended as a taster text or a refresher course on error.

Rhona Flin, University of Aberdeen, UK

In this delightful memoir, Jim Reason provides an amazingly comprehensive and understandable explanation of how and why individuals and organizations make mistakes and what to do about it. A valuable review for experts and a perfect introduction for beginners.

Lucian Leape, Harvard University, USA

This book is an authoritative reminder of the journey to gain acceptance of human error as intrinsic to open systems operations as we enjoy it today, portrayed by the witty pen of one of its topmost trailblazers. I thoroughly enjoyed the book, and found the segment on organizational accidents a particular gem.

Daniel E. Maurino, formerly Coordinator of the Flight Safety and Human Factors Study Programme, International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO)

A fascinating personal and intellectual journey showing the evolution of both James Reasons personal approach and also the broader history of thinking on error and safety. He has a unique gift for making complex ideas accessible within an absorbing and lucid narrative. And all leavened with wonderful examples of human error and some great stories.

Charles Vincent, Imperial College London, UK

Each chapter of this book tells a story where Reason personally confronted a puzzle about accidents, human performance, or organizational decisions. Together the stories build a comprehensive picture of how safety is created but sometime undermined.

David D. Woods, Ohio State University, USA

Chapter 1

A Bizarre Beginning

One afternoon in the early 1970s, I was boiling a kettle for tea. The teapot (those were the days when tea leaves went into the pot rather than teabags) was waiting open-topped on the kitchen surface. At that moment, the cata very noisy Burmeseturned up at the nearby kitchen door, howling to be fed. I have to confess I was slightly nervous of this cat and his needs tended to get priority. I opened a tin of cat food, dug in a spoon and dolloped a large spoonful of cat food into the teapot. I did not put tea leaves in the cats bowl. It was an asymmetrical behavioural spoonerism.

I little realized at the time that this bizarre slip would change my professional lifeI was a lecturer in psychology at the University of Leicester and had run out of research topics. I used to work on motion sickness and disorientation, but students did not like to be made sick and the pool of usable experimental subjects was fast drying up. I needed something new to do. I had flirted with clinical psychology, but I was neither trained nor temperamentally suited for it.

After I had washed out the teapot and sworn at the cat, I started to reflect upon my embarrassing slip. One thing was certain: there was nothing random or potentially inexplicable about these actions-not- as-planned. They had a number of interesting properties. First, both tea-making and cat-feeding were highly automatic, habitual sequences that were performed in a very familiar environment. I was almost certainly thinking about something other than tea-making or cat-feeding. But then my attention had been captured by the clamouring of the cat beyond the glass kitchen door. This occurred at the moment I was about to spoon tea into the pot, but instead I put cat food into the pot. Dolloping cat food into an object (like the cat bowl) affording containment had migrated into the tea-making sequence. Even the spooning actions were appropriate for the substance: sticky cat food requires a flick to separate it from the spoon; dry tea leaves do not. It seemed in retrospect that local, object-related control mechanisms were at work (see later).

I did not realize it at the time, but this action slip exhibited nearly all the principal characteristics of absent-minded errors:

Both behavioural sequences were highly routine, meaning that I was unlikely to be monitoring step by stepmy attention was absent.

Both the cats bowl and the teapot afforded containment.

Some change introduced into a routine sequence of actions (in this case, the cats demands) quite often misdirects actions down the wrong path.

This event was of considerable psychological significance. Although unintended, the individual actions were executed smoothly and skilfully. Among other things, this error suggested a way of investigating the control of highly practiced actions. And these events occurred (in my case) on an almost daily basis and right beneath my nose. After years of laboratory study, I suddenly felt I had access to the fabric of everyday life. Experiments, by definition, are usually carried out in highly artificial (controlled) circumstancesbut I felt very strongly that these naturalistic observations could reveal the stuff of which human thought and action were truly made.

I would like to end this story by describing another absent-minded slip that also took place in my Leicestershire kitchen. For once, I was not the error maker. I rarely get a chance to observe a slip in progress. I was idly watching my wife make tea. She was boiling the kettle and had the teapot beside it with the lid off. Then she reached up to a nearby shelf and took down a large jar of instant coffee. After adroitly unscrewing the lid, she put three teaspoons of coffee into the teapot, poured water into it, and was then alerted to her slip by the strong smell of coffee. Now there was nothing particularly curious in this slip. Errors of this nature happen relatively frequently in our kitchen. What made the slip especially interesting, however, was the skilful way she unscrewed the lid of the coffee jar. The tin tea caddy had a pull-off, push-on lid. The question of interest was, how did her hand perform the appropriate unscrewing movements on the lid? Her mind was clearly absent from the tea-making sequence at the time. My conclusion was that her hand movements were under the local control of the coffee jar. Tea-making and most cooking are test-exit-test-exit tasks.

Next page