Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

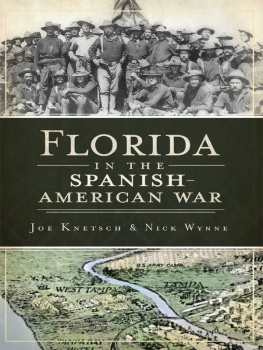

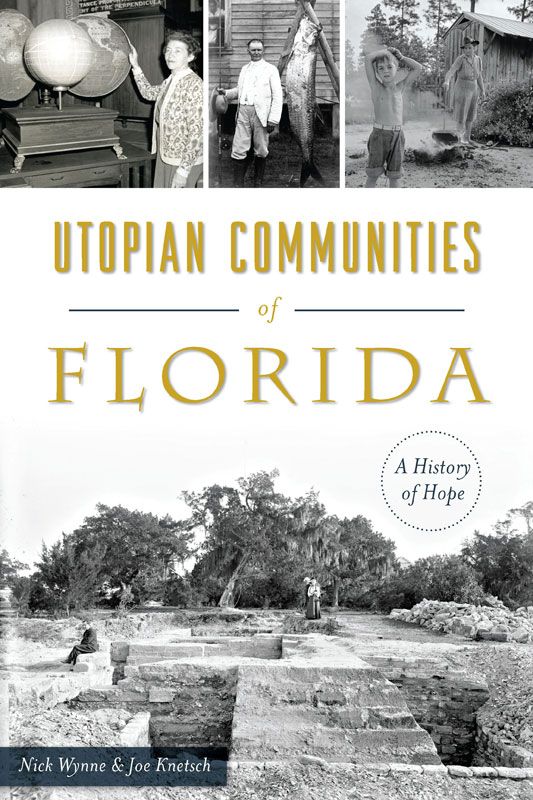

Copyright 2016 by Nick Wynne and Joe Knetsch

All rights reserved

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.43965.902.1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016945912

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.688.4

Notice : The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Professional historians writing on the history of Florida depend on many local amateur historians to help them locate pictures and information about their topics. In many cases, the help given by these individuals fails to earn even a brief mention by the authors. We acknowledge that without the help of other people, we would not have been able to complete Utopian Communities of Florida: A History of Hope. Here are the names of those who contributed (in a variety of ways) to this book: Dr. Irvin D.S. Winsboro, C.S. Monaco, Samantha Mercer, Terri Wolfe, Gordon Pitcher, Dr. Roger T. Grange Jr., Dorothy Moore, Gail E. Griswold, Vishi Garig, Susan Gillis, Sommer Lourcey and our History Press commissioning editor, Amanda Irle.

Additional expressions of gratitude are extended to the men and women who faithfully research, write about and publish the histories of their institutions and towns. These individuals are the keepers of the records and zealously guard their history through acquiring information for the archives of the various historical societies in the state. Given the size and complexity of the Sunshine State and the failure of the states government to adequately fund the State Archives and Library (as evidenced by the efforts of then governor Jeb Bush to close the State Library in 2003), local historians and historical societies represent the first and last defenders of Floridas past. Thank you.

The authors would also like to recognize the efforts of the late Dr. James J. Horgan of St. Leos University in documenting the history of Pasco County, St. Leos and the Dunne settlement of San Antonio.

INTRODUCTION

The first things the reader of this volume will notice are the topics of this introduction. Although our intent is to introduce a number of communities that began as experiments, not all fit into the definition of Utopianism in the usual meaning of that word. Utopia, or the idea of it, comes from the writings of Sir Thomas More, who described a perfect society where strife was forbidden, everyone was allowed to do as they pleased as long as it did not interfere with the happiness of their fellow Utopians and there was no want for food, comfort or companionship. It was the ideal society for all. It was also his dream, and one that has yet to be realized. Communitarianism, on the other hand, is a conscious effort to set up an ideal society as a model for all others to follow. It is usually a small-scale social experiment but an indispensable first step in showing others the way to a better lifea pilot plan, if you will. When a communitarian dreams of a utopia, it is most often characterized as a small-scale experiment that was meant to be replicated indefinitely. In the words of Arthur E. Bestor, The communitarian conceived of his experimental community not as a mere blueprint of the future but as an actual, complete functioning unit of the new social order. Many of the communities noted in the history books as utopian are, in Bestors mind, really communitarian settlements created as experimental models.

Some of the more noted utopian communities in American history have religious origins, like the Shakers, Hutterites and Rappites (known more commonly as Harmonists). Many of the members of these early social experiments were of Germanic origins and were fleeing wars in Europe or the strict religious controls of the Lutheran Church. Their goals were to set up religious-based separate communities where they could live and worship without the restrictions of an outside religious organization. Florida had two totally religious-based communities: that of Moses Levy, on behalf of his fellow Jews who faced persecution everywhere in Europe, and Judge Edmund Dunnes Catholic colony at San Antonio. Dunne had lost his position as chief judge in Arizona because of his proposal to use public funds for the Catholic schools of the territory. Although these communities were not utopian in the strictest sense of that concept, they were founded to allow their co-religionists a chance to form distinct communities where members could govern their members based the principles of a shared history and a common system of beliefs.

Cyrus Teed and his followers established a truly utopian community at Estero (the Koreshan community) that was heavily influenced by the ideas of George Rapp, the founder of New Harmony and Economy. The Harmonists were waiting for the second coming of Christ, which they believed would happen in America. Rapp and his followers were fleeing the domination of the Lutheran Church in Germany and immigrated to the United States in search of a place where they could practice their faith without the condemnation and persecution of the Lutheran Church. They first chose to settle in Pennsylvania and later moved to Indiana before settling once again in Pennsylvania. Teed was seeking to establish a Zion in the Wilderness in Florida after being harassed in New York and Chicago. Rapp and Teed declared themselves to be prophets who served as solitary links between God and their communities. Cyrus Teed established himself as the new prophet who interpreted the world (concave, in his case) for his followers and demanded of his followers, as had Rapp, close to total obedience to his pronouncements. Although not utopian philosophers in the classic sense of the term, Teed fits the utopian model because of his many publications expounding his visions and describing the glorious future awaiting his followers and co-religionists.

All of the communities discussed herein have one thing in common: the hope for a better life. Most are reactions to economic depressions, religious oppression or myriad other afflictions that prevented the members from achieving their desired community. On the secular level, we see the attempt to found communal societies based on new ideas for educating the young and providing a secure economic future for the community as a wholefor example, the Ruskin settlements movement that gave Florida two still viable communities, Ruskin and Crystal Springs. The goal of setting up a scientific farming community based on cooperative ventures in living spurred the great retailer James Cash Penney to invest in his experimental community at Penney Farms, in Clay County. His deep and sincere commitment to his Christian beliefs also led him to include a retirement community for retired ministers, YMCA workers and missionaries in his plans.

Not all of the experimental communities in Florida were founded on religious principles or philosophical theories. One of the earliest attempts to create a new community, the colony of New Smyrna by Andrew Turnbull, was based on the simplest of motivations: profits to be made by the financial backers of the project and the acquisition of land by penniless laborers. Religious differences between Catholics and Protestants were initially ignored, but they soon bubbled to the surface. Combined with personality disputes between powerful government officials and the owners of the colony, religious conflict eventually spelled doom for the New Smyrna community.