Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my teachers Ross MacIntyre, Bruce Wallace, and James Edwards, who introduced me to the wonder of genetic thinking, experimentation, and interpretation.

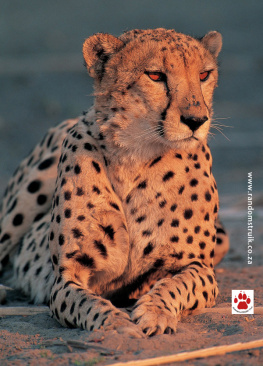

There is no better way to introduce a beginner into the achievements of molecular biology than Stephen J. OBriens Tears of the Cheetah. Some early biochemists loudly proclaimed that molecular biology would exterminate the rest of biology. There is only one biology, one of them said, and This is molecular biology. Nothing could have been more wrong. Instead, the study of molecules has enormously enriched organismic biology and led to astonishing discoveries in just about all branches of biology. OBrien, in fourteen chapters, shows in case study after case study how the molecular discoveries of genomes have shed unexpected light on such problems as the loss of genetic variation in the cheetah, the Florida panther, and the Asian lion; how we can find the degree of genetic difference among populations of whales, of Indonesian orangutans, and of many species of uncertain taxonomic rank; why the unique mating system of lions is not in conflict with kin selection; how AIDS originated, and why it is so resistant to all medical effort. Immune genes tell us about historical epidemics hundreds or thousands of years ago. These fascinating scenarios are told by OBrien with such literary mastery that one can hardly lay his book down.

In chapter 10 the extraordinary similarities of the genomes of different mammals (including the human) are presented, and it is pointed out to what great extent the solution of human medical problems is helped by comparative studies of the genomes of other mammalian familiesfor instance, cats. Though often dealing with highly technical matters, OBrien has succeeded in presenting his stories in a simple language that can be understood even by the nonexpert. And he also persuades us how important the findings made on animals often are for human medicine. There is no other book I have read in recent years from which I have learned more, and which I have more enjoyed, than this one. And so will every reader.

Ernst Mayr,

Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology,

Emeritus, Harvard University

The book you have opened contains a collection of stories. They are adventures, they are science mysteries, they are medical enigmas, and they are detective stories. Most draw their theme around an inimitable threatened animal species and scientific advances that unveil past and present dangers. The chronicles are all true and in different ways illustrate the power of new genomic technologies to uncover hidden secrets in the history of wildlife species, of companion animals, and of ourselves.

At first glimpse these tales describe the peril of beloved endangered speciescheetahs, humpback whales, giant pandas, and others. What we discovered beneath the surface of the fragile wildlife species reveals the rationale and context for their successes, for their survival, and for their vulnerability. The new perspectives derive from reading genetic codes of living species, only recently available for inspection. The spectacular developments in genetic technology and gene identification can be applied to any species with surprising and sometimes disturbing results. From the viewpoint of evolutionary hindsight, a thousand fables are slowly emerging through the lens of modern genomic enquiries. What began as a quest for reversing species extinction opened my eyes to as rich a history of magnificent creatures as anyone could have imagined. The genetic thread that strings these stories together is the indisputable unity of all living things. We are all intricately joined by a vast, weblike genealogical network to our most ancient ancestors.

The genomes of modern mammals, the sum total of an individuals genetic instructions, contain an extraordinary cache of information. In their genetic endowments of three billion nucleotide letters reside thirty-five thousand to fifty thousand genes that specify each creatures development. But they also retain the script of historic brushes with extinction, adaptation, and survival. Every day natures dutiful field experiments test new gene variants across individuals in populations, among species, and across geographical space. All these trials have been neatly catalogued in the genetic sequence of the survivors, the plants and animals alive today. Scientists are only beginning to interpret the genetic pawprints of ancient events. We are learning as we go how to discern the message and lessons in DNA. Though progress may seem slow, the early views on this genetic safari have galvanized our thinking and optimism for solving countless mysteries about how living things came to be.

The genomics era appears to have unprecedented promise and potential for nearly every aspect of biology. It is as if the printing press were just invented and we anticipate the wide dissemination of the thoughts, ideas, feelings, and experiences of a whole generation. The difference is that our collective genomes encode the lessons of not one but tens of thousands of writers, multiplied across every evolutionary lineage while also possessing their own unique and defining experience. As the periodic table empowered chemical design and the silicon chip changed all things computational forever, so will our cracking the genome be remembered as a turning point in the underpinning of biological happeningspast, present, and future.

An underlying theme of the science mysteries is the unusual insight that animal studies bring to human medicine. Wild species have no hospital emergency rooms, no HMOs or pharmacies to treat their ills. Still they are regularly assaulted with scourges nearly identical to those that afflict humanscancers, deadly infectious diseases like AIDS and hepatitis, degenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimers, and arthritis. Many victims succumb and die; indeed, well over 99.9% of all mammalian species that have walked the earth have gone extinct. But others have escaped, and those lucky species survive quietly today, carrying the evolved secrets to their success in their genetic endowment. Can medical science learn from natural solutions to hereditary, infectious, and neoplastic diseases acquired by free-living orangutans, lions, cougars, and barn mice? I believe we can, and I will illustrate how by the examples in the coming chapters.

These stories offer a window into twenty-first-century science, where undoubtedly countless biomedical advances will come from mining the genome. These are parables of hope and lessons of survival. They also navigate through the torturous but exhilarating process of scientific discovery, interpretation, and policy development.

Each chapter tells its own special narrative with twists and turns no novelist would have imagined. I selected them because I have been personally involved with each and with the lead characters I describe. The cast of players are scientists, graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, physicians, veterinarians, field ecologists, and many others who play into the mix of research advancement. I have had the privilege of joining these adventures as a government scientist, employed as a geneticist for thirty years at the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH).