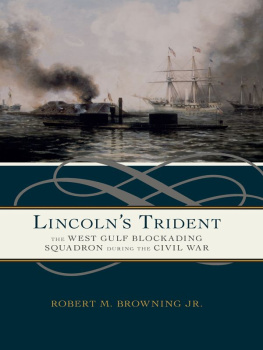

ROBERT M. BROWNING JR.

Inquiries about reproducing material from this work should be addressed to the University of Alabama Press.

The paper on which this book is printed meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Browning, Robert M. Jr., 1955

Lincolns trident : the West Gulf Blockading Squadron during the Civil War / Robert M. Browning Jr.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8173-1846-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8173-8778-5 (ebook)

1. United States. Navy. West Gulf Squadron. 2. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Blockades. 3. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Naval operations. 4. Farragut, David Glasgow, 18011870Military leadership. 5. Mississippi River ValleyHistoryCivil War, 18611865. 6. Gulf Coast (U.S.)History, Naval19th century. 7. Mexico, Gulf ofHistory, Naval19th century. 8. United States. NavyHistoryCivil War, 18611865. I. Title.

E600.B83 2014

973.758dc23

2014019856

Preface

After the Civil War Admiral David Glasgow Farragut wrote, Historians are not always correct; I maintain the conviction that whatever errors may be made by the hands of historians and others, posterity will always give justice to whom justice is due. Since Farraguts death, historians and the admirals peers were extremely just. Many believe he is the greatest man to wear the uniform of the United States Navy. His contemporaries, and historians alike, have written more about the exploits of Farraguts squadron than any other naval officer during the war. Even before the war ended, men began writing about his actions and achievements.

In the spring of 1862, the Navy Department established the West Gulf Blockading Squadron and it operated along an expanse of over one thousand miles of coastline, from Saint Andrews Bay, Florida, to the Rio Grande. Farragut, the squadrons first commander, kept this position until the fall of 1864, after the Battle of Mobile Bay. While the blockade was one of the major functions of the squadron, it also importantly served to project force strategically. Not unlike the Greek god Poseidon who struck the ground with his trident to cause earthquakes, tidal waves, and storms at sea, the squadron served similarly as President Abraham Lincolns trident to accomplish his military goals. As a power projection asset, the squadron made thrusts up the Mississippi River and into the heart of the Confederacy. It fought battles, supported troop movements, controlled interior waterways, all the while maintaining its blockading responsibilities. Lincolns trident had a long reach and a huge influence on the war effort. The Union warships were an overpowering force that the Confederates could not restrain, much as Poseidons powers were to his rivals.

While the squadrons actions were strategically critical to defeating the Confederacy, the disjointed Union efforts in the Western Theater often caused a wasteful use of this superior force. Shown repeatedly, the Union leadership inWashington had no real joint strategy that used the army and naval forces in a joint long-term strategic plan. Both military branches aided each other in common goals, but the absence of an encompassing wartime strategy prevented the Union forces from exploiting their successes. With no clear strategic vision from the Washington leadership, the war in the West was a series of disorganized efforts. Because of this, the history of the squadron and the struggles in the Western Theater saw victories and failures, unfulfilled expectations, and lost opportunities. Clearly, however, without the presence of the greatly superior Union naval forces, the military gains in the West would have likely been impossible. Certainly, the navys presence shortened the war, and the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, under Farraguts leadership, was a major component in attaining victory.

A squadron history is a story of many separate parts, acting in different enterprises over a great expanse. It is a narrative relating the action of men, ships, battles, and leadership, all influenced by many variables. As a command, the squadron, however, interacted well to defeat the Confederates under the leadership of Americas greatest naval commander. Farragut was right, historians are not always correct, but the admiral has certainly received justice in their eyes.

Acknowledgments

An old English proverb states, Gratefulness is the poor mans payment. For historians, this is an appropriate phrase because we always owe unpayable debts to those who help us. Assistance, encouragement, and support from colleagues, friends, and institutions all shape the final product. The assistance of the staff at the National Archives was key in the completion of this book. Susan Abbott, Mary Ladner, Becky Livingston, and particularly Rick Peuser and Mark Mollan were instrumental in this project. Thanks also go to the staff at the Library of Congress who made many resources available. The staff at the Naval History and Heritage Command, in particular Glen Helm and the library staff, and Chuck Haberlein, Ed Finney, Lisa Crunk, and Robert Hanshew of the photographic division, were superb. The staffs of many other institutions were critical as well. Thanks go to Bill Edwards-Bodmer and Bill Barker at the Mariners Museum; Heather Smedberg at the Mandeville Special Collections Library at the University of California, San Diego; Molly Kodner from the Missouri Historical Society Library; Dr. Jennifer Bryan, Dorothea Abbott, and David DOnofrio at the Special Collections at the United States Naval Academy, and Tim Salls at the New England Historic Genealogical Society. I would like to thank Robert Clark at the FDR Presidential Library and the staff of the Morgan Library; Ed Frank from Special Collections at the Ned R. McWherter Library, University of Memphis; and David Kuzman and Albert King in Special Collections and University Archives at Rutgers University. John Stinson and Don Mennerich from the Manuscripts and Archives Division at the New York Public Library; Chris Baer at the Eleutherian Mills, Hagley Foundation; Lita Garcia at the Huntington Library; and Nicolette Schneider and Diane Cooten at the Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University, provided important documents and information. Silva Blake from the Historic New Orleans Collection; Melissa Smith from the Manuscripts Department, Special Collectionsat Tulane University; and Ted OReilly at the New York Historical Society aided this project greatly. Special thanks go to Nick Wyman in Special Collections, John C. Hodges Library, University of Tennessee; and Jim Cheevers at the US Naval Academy Museum, who both provided critical Farragut correspondence. Thanks go to the Chicago Historical Society; AnnaLee Pauls at Princeton University; and Erin OBrien and Amelia Abreu at the Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin, for their help. Connie Hammond and the Western Reserve Historical Society Library and Archives, and John Coski at the Museum of the Confederacy, were both extremely helpful. Beth Bigley and Barbara Firich and the Interlibrary Loan staff at the Prince William County Library helped me throughout the writing of this manuscript and I cannot thank them sufficiently for their assistance. Thanks also go to Skip Theberg and John Cloud at NOAA for their help with historic maps. Others who helped include John Koster, Ed Cotham, Stauffer Miller, and Jim Delgado. I appreciate the special assistance and patience of Joseph Powell, Dan Waterman, Dawn Hall, and Jon Berry at the University of Alabama Press. I would like to give special thanks to Bill Still, Bob Holcombe, Steve Wise, Bill Thiesen, Kevin Foster, Scott Price, and Chris Havern for reviewing the manuscript. Their help has definitely made the final product better. Last, and most important, is the help, patience, assistance, and support I received from my wife, Susan. Without her, I am not sure this book would have ever seen publication.