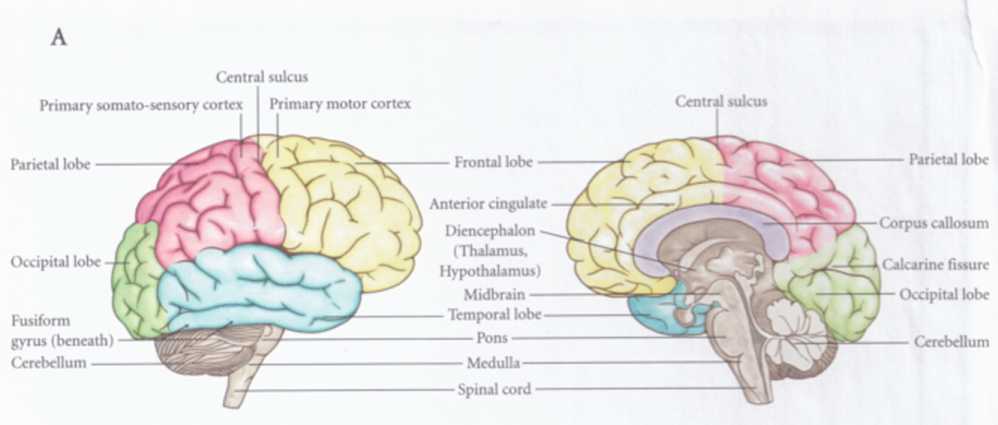

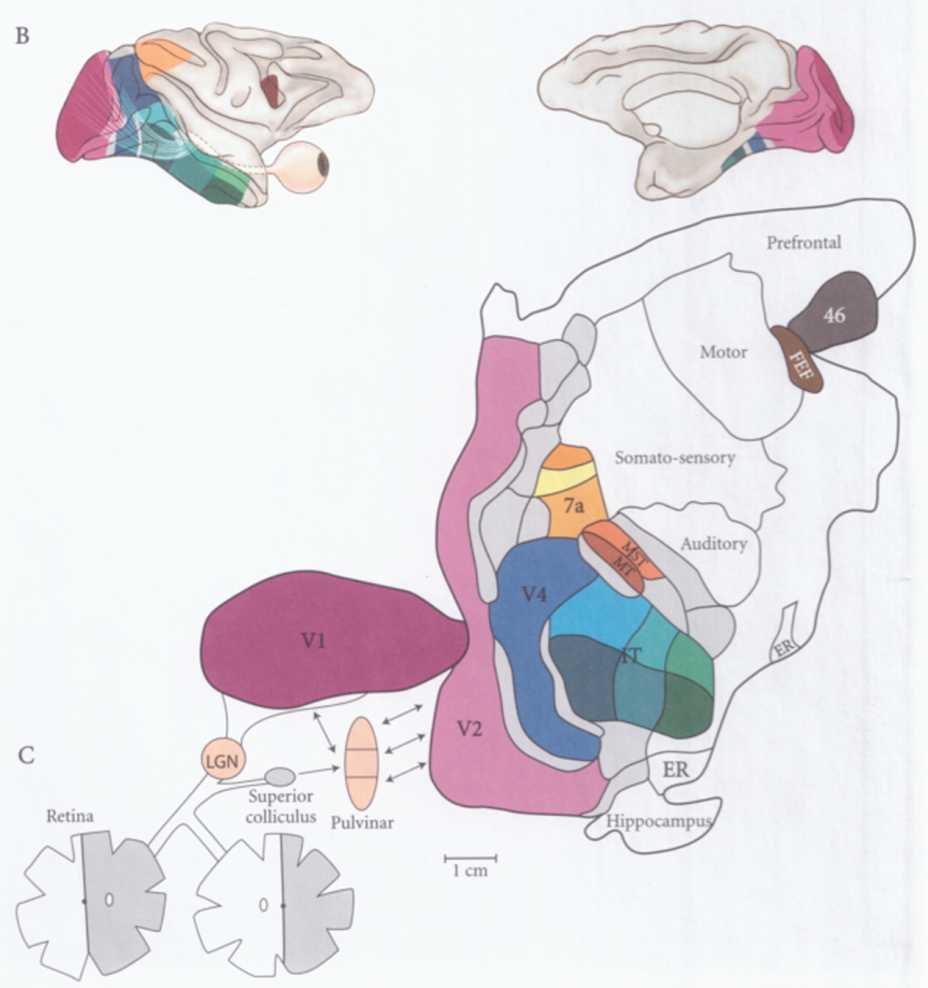

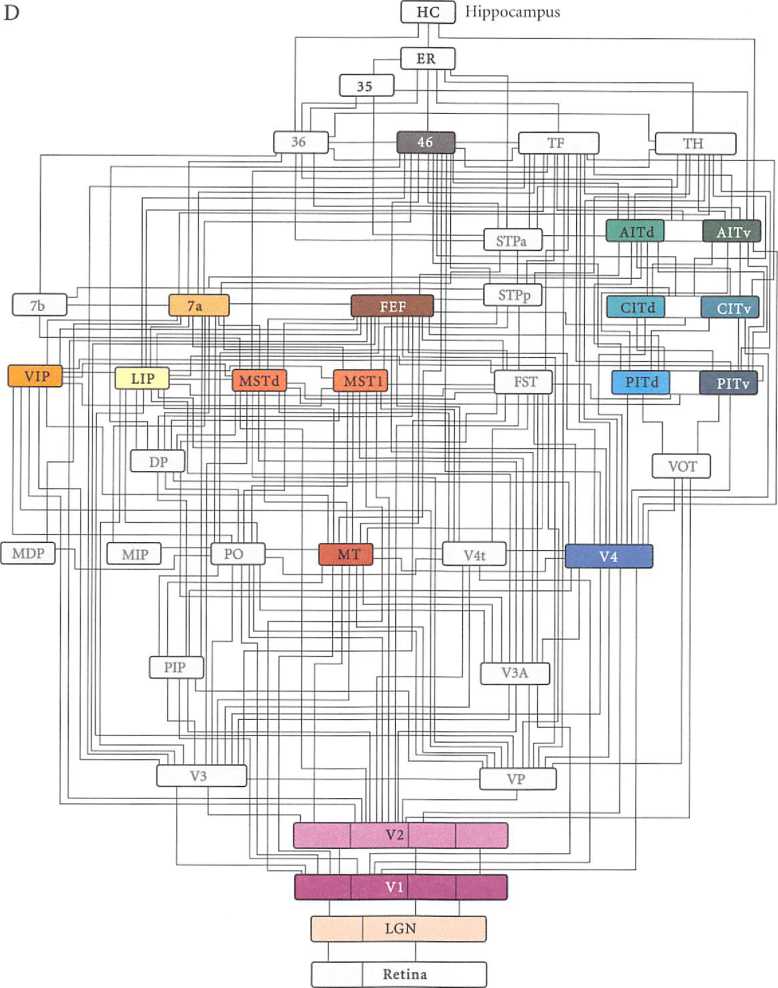

(A) Lateral (left) and medial (right) view of the human brain. (B) Two similar views and (C) an unfolded and flattened map of the macaque's monkey brain. All non-white areas are involved with visual processing. The human and monkey brains are drawn at different scales. (D) Organizational chart of the monkeys visual System. Optical information flows from the retina in a qUasi-hierarchical manner through a large number of cortical areas. Most of the links are reciprocal. Only the retina, LON, VI, and V2 are drawn with some of their substructures. (B)-(D) are modified from Van Essen and Gallant (1994) and Felleman and Van Essen (1991). For more anatomical information, see http://brainmap.wustl.edu.

The Quest for Consciousness

A Neurobiological Approach

Christof Koch

Roberts and Company Publishers Englewood, Colorado

I dedicate this book to

FRANCIS CRICK

Friend, Mentor, and Scientist

Foreword by Francis Crick

We do not know in advance what are the right questions to ask, and we often do not find out until we are close to the answer.

From Steven Weinberg

It is a pleasure to write an informal introduction to this unusual and excellent book. Most of the ideas in it have been developed by Christof and myself in continual collaboration, as our joint papers show, and Christof has involved me in much of the writing of it, though the hard work, and the breezy, informal yet well-reasoned style are all his own. So mine is not an unbiased assessment.

I strongly recommend it to the main audience for which it is intended, which is, in round terms, not merely neuroscientists, but scientists of all sorts with an interest in consciousness.

Consciousness is the major unsolved problem in biology. That there is no present consensus on the general nature of the solution is made clear by Christof in Chapter 1. How do what philosophers call qualia, the redness of red and the painfulness of pain, arise from the concerted actions of nerve cells, glial cells and their associated molecules? Can qualia be explained by what we now know of modern science, or is some quite different kind of explanation needed? And how to approach this seemingly intractable problem?

In the past dozen years there has been an enormous flood of books and papers about consciousness. Before that the behaviorist approach, and, surprisingly, much of the initial phase of cognitive science which replaced it, effectively stifled almost all serious discussion of the subject.

What is different about this book? Rather than another closely argued and largely sterile discussion of the root of the mind-body problem, our strategy has been to try first to find the neuronal correlates of consciousness (often called the NCC). Because of our emphasis on the behavior of neurons we have concentrated mainly on topics that can be studied in the macaque monkey, while including parallel work on humans. Thus, both language and dreams receive little or no emphasis. How would you study a monkeys dreams?

We have also avoided some of the more difficult aspects of consciousness, such as self-consciousness and emotion, and concentrated instead on perception, especially visual perception. And we have tried to approach visual perception at a number of levels, from visual psychology, brain scans, neurophysiology and neuroanatomy, down to neurons, synapses, and molecules.

This involves digesting an enormous number of experimental observations, some of which inevitably will turn out to be wrong or misleading, while at the same time trying out various theoretical hypotheses. These ideas are seldom totally novel, though the combination of them may be new.

Thus, parts of die book are necessarily heavy on facts. This is especially true of the chapters on the details of the macaque visual system, but Christof has a recapitulation at the end of each chapter (except for Chapter 19, which is a recapitulation of most of the book), so that the reader can, the first time round, skip some of the details. ,

Another unusual feature is that, for a book with so many facts, it is a delight to read. Christofs informal style, which would be strictly banned by the editors of scientific journals, carries the reader along. It also conveys quite a bit about Christofs background and tastes, from his love of dogs to his very catholic love of music, with quotations ranging from Aristotle to Woody Allen, and from Lewis Carroll to Richard Feynman and Bertie Wooster.

While easy to read, Christof has provided, in the convenient footnotes and references, a guide to both broad surveys and key papers, so that the interested reader can easily begin to explore the very extensive literature on almost all the relevant topics.

Solving the problem of consciousness will need the labors of many scientists, of many kinds, though it is always possible that there will be a few crucial insights and observations. The book is designed as an introduction for scientists, especially younger ones, with the hope that it will lead them to contribute to the field. A few years ago one could not use the word consciousness in a paper for, say, Nature or Sciencey nor in a grant application. But thankfully, times are changing, and the subject is now ripe for intensive exploration. Read on!

Preface

We must know. We will know.

Epitaph on the gravestone of David Hilbert, German mathematician

X had already taken an aspirin, but the toothache persisted. Lying in bed, I couldnt sleep because of the pounding in my lower molar. Trying to distract myself from this painful sensation, I pondered why it hurt. I knew that an inflammation of the tooth pulp sent electrical activity up one of the branches of the trigeminal nerve that ends in the brainstem. After passing through further switching stages, pain was ultimately generated by activity of nerve cells deep inside the forebrain. But none of this explained why it felt like anything! How was it that sodium, potassium, calcium, and other ions sloshing around my brain caused this awful feeling? This mundane manifestation of the venerable mind-body problem, back in the summer of 1988, has occupied me to the present day.

The mind-body dilemma can be expressed succinctly by the question, How can a physical system, such as the brain, experience anything? If, for example, a temperature sensor coupled to a computer becomes really hot, the processor may turn on a red alarm light. Nobody would claim, however, that the flow of electrons onto the gate of die transistor that closes the light switch causes the machine to have a bad day. How is it, then, that neural activity can give rise to the sensation of a burning pain? Is there something magical about the brain? Does it have to do with its architecture, with the type of neurons involved, or with its associated electro-chemical activity patterns?

The matter becomes even more mysterious with the realization that much, if not most, of what happens inside my skull isnt accessible to introspection. Indeed, most of my daily actionstying my shoes, driving, running, climbing, simple conversationwork on autopilot, while my mind is busy dealing with more important things. How do these behaviors differ neurologically from those that give rise to conscious sensations?