First edition published 1887

This edition first published 2015

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

Copyright Amberley Publishing, 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781445644837 (PRINT)

ISBN 9781445645032 (eBOOK)

Typesetting and Origination by Amberley Publishing.

Printed in the UK.

Contents

Editors Note

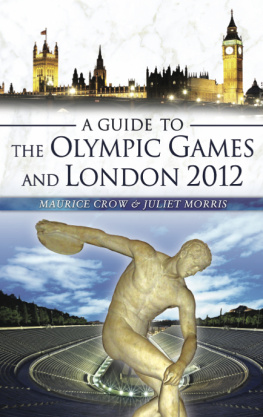

The history of athletics dates back to the era of blood and sand in Ancient Greece, where the grand Olympian Games paid tribute to the mighty god, Zeus. Over time, the honoured games have cemented themselves within our culture, venturing outside of Greece and spreading across the world as a global sporting phenomenon. Now, the infamous collection of sporting events focuses less on Greek mythology and more on the fierce competition, determination and dedication to sport.

From road running, race walking, cross-country running, mountain running and track and field, athletics has proven to be one of the most regularly competed sports to exist. The fact that it does not require the use of expensive equipment makes athletics even more available to potential athletes, giving them the opportunity to showcase their individual sporting talent.

Beyond the Greek games, athletic contests have existed in various countries: in Ancient Egypt there are illustrations of high-jumping on tombs; there was the Celtic festival of the Tailteann Games in Ireland in 1800, and in seventeenth-century England, the introduction of the Cotswold Olympick Games. It was the Royal Military College in Sandhurst, England, that claimed to be the first to use the metric system for athletics in 1812 and 1825, but there was no evidence to support this. However, there is evidence of recorded athletics meetings in the UK, with one in 1840 organised by the Royal Shrewsbury School Hunt. This was followed by an organised competition by the Royal Military Academy at Woolich in 1849, and a series of meetings available only to undergraduates at Exeter College, Oxford, in 1850.

With so vast a history to cover, when it came to the studious task of compiling a guidebook for the progression of athletics, it needed to come from someone well-equipped with the foundations of the games. Thus, it was in 1887 that Sir Montague Shearman did just that. More than qualified for the role, Shearman had enough knowledge and experience with athletics to pen Athletics and Football. Starting off as a founding member of the Amateur Athletics Association commonly known as the A.A.A., which was established in England in 1880 Shearman later became the first honorary secretary from 1880 to 1883, vice-president until 1910, and eventually, president.

As well as a judge and art collector, Shearman remained the ever resilient sportsman, continuing to work despite suffering a speech impairment from an operation triggered by an old football injury. He passed away, aged seventy-two, in 1930, at his London home, just one year after his retirement.

Laura Nicklin

Editor

2015

Introduction

It may seem strange that I should be asked to turn aside from the studies and occupations which have so closely engaged my time during the last twenty years, to write a few lines upon a subject in which during that period, and for years before, I have taken the greatest interest, namely, athletics; and yet it is not altogether unfitting, inasmuch as I am probably as well qualified as any to speak from personal experience of the advantages which are gained in a sedentary life from the power of practising active exercises. Except cycling and lawn-tennis, both of which have been practically invented during the last fifteen years, no pursuit has seen so great an advance or revival as athletic sports. It may be, and it probably is, the case (as those who read the pages of this book will learn), that for a great many years prior to the year 1850 athletic sports had been from time to time pursued by both amateurs and professionals, who had with more or less assiduity, according to the particular ability or powers of the competitor, performed before the public; there had been, no doubt, remarkable instances of individual men who possibly had been as great at running, walking, jumping, and swimming as those who have excelled in modern times; but it is perfectly certain that prior to the date last mentioned I mean the year 1850 athletics were not practised as a recognised system of muscular education, nor was there any authentic record of individual performances. I doubt, moreover, whether either times or distances were taken and measured with sufficient accuracy to make the earlier records in any way trustworthy.

A steeplechase.

Speaking of our Universities, I have seen the foundation of the present prosperous clubs at both Cambridge and Oxford, and, with the exception of the crick-run at Rugby and the steeplechase at Eton, prior to 1850 no public school had any established athletic contest. I do not, however, propose in the few lines which I intend to pen to attempt any history of athletic sports; the following pages will, I am sure, contain records attractive both to the athlete and the public, of those who, in years gone by and down to the present time, have excelled on the road, the turf, and the running-path. I wish for a few moments to regard the subject from the point of view of the consideration of the advantages to be gained in the practice of athletics, and, secondly, to make a few suggestions as to the best mode in which these advantages may be increased so as to be of still greater utility and benefit.

We are brought face to face in England, and other populous countries, with the difficult problem which is called into existence by over-population, and the utter absence of space and opportunity for the youth of the present day to find sufficient scope for his energies. The tendency to crowd into the curriculum of both school and college a large and ever-increasing number of subjects has rendered the strain of education far heavier than in times gone by, and this tension will certainly increase.

In old days, when a fair grounding in Greek and Latin, or a moderate knowledge in mathematics, was a sufficient preparation for almost any profession (the brilliant few being left to excel in those subjects by the sheer force of their natural abilities), the culture of the body and the simultaneous development of physical and mental strength were of less importance, or at any rate their value was less recognised. I need scarcely remind those who read these pages that, thirty years ago, it was the exception for a senior wrangler or a senior classic to figure in the University boat or the eleven. The names of those few who did excel stand out among their contemporaries, and it was by no means an uncommon experience to find that those who had surpassed in intellectual contests in school and college utterly broke down in their professions in after life. I attribute this in no small degree to the fact that for many boys and men there was scarcely any inducement to develop or use their physical strength, nothing which led them to those pursuits which, without engrossing the mind too much, develop the body gradually and contemporaneously with mental growth. How many a first class man at Oxford, or wrangler or first class classic at Cambridge, could only find exercise in the daily and monotonous grind of an hour or an hour and a halfs walk; cricket and boating both taking up too much time, and not unfrequently leading many to expenses which they could ill afford?