CHURCHILL:

THE STATESMAN AS ARTIST

In memory of Mary Soames

CONTENTS

Eric Newton

Thomas Bodkin

John Rothenstein

Augustus John

Thomas Bodkin

John Rothenstein

Paintings by Winston S. Churchill

Photographs

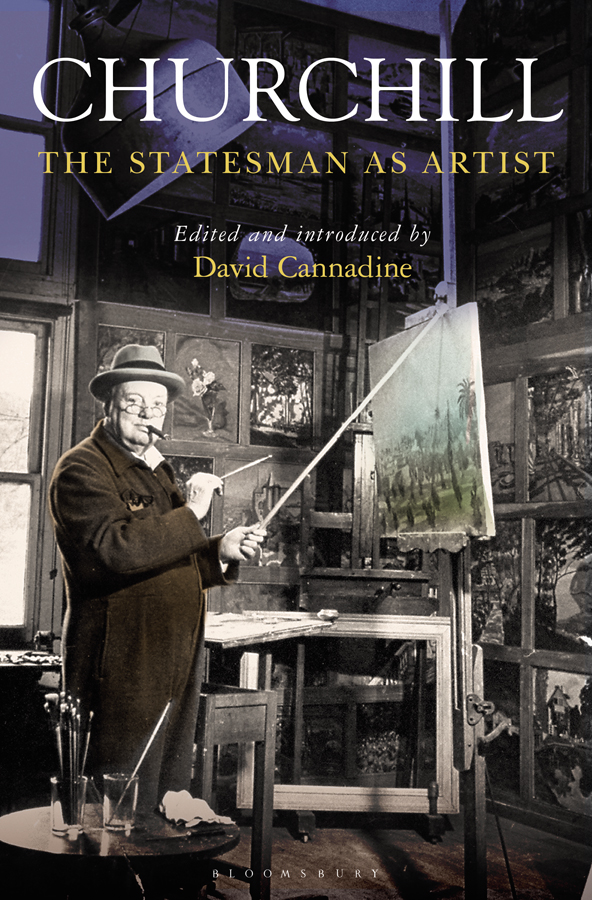

Most of this book consists of Winston Churchills own thoughts on art, and the views of contemporary critics on him as an artist. These writings have never previously been gathered together, and that in itself is ample justification for the appearance of this volume. They tell us important things about Churchill, and about his reputation in his time; and while his own writings on art are, like most of his pictures, consistently buoyant, joyous and highly-coloured, he painted primarily to keep depression at bay, and also because it provided another outlet for the display of his extraordinarily creative gifts. Statesmen who are also artists are very rare, and Churchill is by a substantial margin the best documented of them.

Although I have long been fascinated by Churchill as one of the great historical figures of the twentieth century, my interest in him as a painter was only aroused when I was invited to deliver the Linbury Lecture at Dulwich Art Gallery on that subject, and it was further stimulated when I recorded a series that was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 entitled Churchills Other Lives. Accordingly, my first thanks are to Lord Sainsbury of Preston Candover and the Trustees of the Linbury Trust, and to Dr Ian Dejardin, the then Director of the Dulwich Picture Gallery, for inviting me to lecture on Churchill as an artist; and to Denys Blakeway and Melissa Fitzgerald, of Blakeway Productions, with whom I made Churchills Other Lives.

In researching Churchill the painter in the archives, I am once more indebted to Allen Packwood, Director of the Churchill Archive Centre at Churchill College, Cambridge, and his unfailingly knowledgeable and helpful colleagues. I am grateful to Dr Charles Saumarez Smith, Secretary and Chief Executive of the Royal Academy, and to Mark Pomeroy, the Academys Archivist, for their assistance and advice. I also thank Bart H. Ryckbosch, the Glasser and Rosenthal Family Archivist at the Art Institute of Chicago, and Teri Edelstein for putting us in touch. Once more, the assistance and forbearance of Dr Martha Vandrei have been invaluable.

In working on this project, I have been enormously fortunate in my two editors at Bloomsbury, Robin Baird-Smith and Jamie Birkett, who have seen a complex book through to publication with great resourcefulness, dedication and skill, and I also express my thanks to their colleagues, Sutchinda Thompson, Graham Coster, Hannah Paget and Chloe Foster. I am grateful to Curtis Brown, who represent the Churchill Estate, and in particular to Gordon Wise, to the National Trust staff who work at Chartwell, and to Mr Randolph Churchill for his generous help and encouragement. Thanks to them, no less than to Churchill himself, this book reveals his life in art more vividly than ever before.

David Cannadine

Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study

Uppsala

30 November 2017

by David Cannadine

Winston sees everything in pictures

Lord

During the last years of his life, Winston Churchill was often acclaimed as the greatest Englishman of his time and the saviour of his country, and he is still regarded by many as the most remarkable human being ever to have occupied 10 Downing Street, and as the greatest Briton ever to have lived.

I

Among the hundreds of paintings Churchill completed during his lifetime were many of the interiors and exteriors of Blenheim Palace, and they were one indication of the abiding importance to him of his ancestral home [ But the disappearance of virtually all the best art from Blenheim during Churchills adolescence may explain why he never evinced any serious interest in European Old Masters, or in traditional English portraiture.

This depletion may also help explain why Churchill would later claim that he had demonstrated no appreciation of art at any time during the first forty years of his life, and that his own creative endeavours had been confined to a few drawings reluctantly and unsuccessfully undertaken while he was at school and serving in the army. Such was his recollection, as reported years later, by Clementine Churchill, and as recorded by his doctor, Lord Moran:

When Winston took up painting in 1915, he had never up to that moment been in a picture gallery. He went with me to the National Gallery [in London], and pausing before the first picture, a very ordinary affair, he appeared absorbed in it. For half an hour, he studied its technique minutely. Next day, he again visited the Gallery, but I took him in this time by the left entrance instead of the right, so that I might at least be sure that he would not return to the same picture.

Before that visit, Churchills closest encounters with art had been his early attendances, beginning in 1908, at the Royal Academy banquets, held in Burlington House on Piccadilly, which were a highlight of the London season and inaugurated the Academys annual summer exhibition. But he was invited to these gatherings as a member of the Liberal government, not because he was expected to have anything significant to say about sculpture or painting or architecture. When Churchill delivered his first two speeches, in 1912 and 1913, he did so as First Lord of the Admiralty, replying the toast of the Navy, and on both occasions he was primarily concerned to assert the continuing and urgent need to maintain Britains formidable sea power and maritime might. Modern ships, he noted in his second speech, almost by way of an afterthought, do not afford much ground for artists to work upon. We cannot, he went on, speaking for the Navy as a whole, but also for himself, on the aesthetic or the artistic side claim any close acquaintanceship with the Royal Academy.

Churchills middle-aged indifference to art was all of a piece with the account that he would later give, in My Early Life (1930), of his academic shortcomings as a schoolboy, where he depicted himself as having been hopeless at mathematics and incapable of mastering Latin or Greek.

Yet while it was and is easy to dismiss him as being culturally uninformed, intellectually incurious and aesthetically unsophisticated, Churchill also possessed remarkably potent mental machinery, albeit academically untrained, and for a public figure he was also unusually creative and imaginative. Kenneth

But it was also clear to many observers and contemporaries, from General

Although widely distributed among his descendants and relatives, these creative impulses were especially pronounced in the case of Churchill himself. From an early age, he seems to have been gifted with the heightened perception of the artist, to whom no scene, no event, no individual was ever dull or humdrum or commonplace. This was most famously true in his use of the English language, which he handled in his conversation, his speeches, his journalism and his books with a sure touch, a sensuous feel and an imaginative brilliance, as he delighted in strong nouns, vivid adjectives, rich imagery, polished antitheses, glowing phrases and powerful rhetorical effects. There was nothing dull or humdrum or commonplace about Churchills choice or use of words, and although his paintings lacked the stately splendour, the formal magnificence and the heroic grandeur of his greatest orations, they strikingly resembled them in other ways.