Contents

ALBERT CAMUS

The Myth of Sisyphus

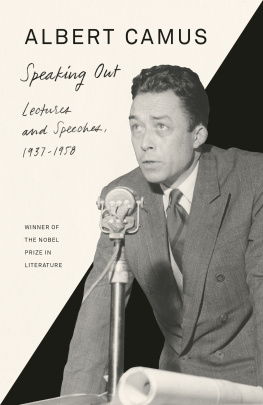

Albert Camus, son of a working-class family, was born in Algeria in 1913. He spent the early years of his life in North Africa, where he worked at various jobsat the weather bureau, an automobile-accessory firm, a shipping companyto help pay for his courses at the University of Algiers. He then turned to journalism as a career. His report on the unhappy state of the Muslims of the Kabylie region aroused the Algerian government to action and brought him public notice. From 1935 to 1938, he ran the Thtre de lquipe, a theatrical company that produced plays by Malraux, Gide, Synge, Dostoevsky, and others. During World War II, he was one of the leading writers of the French Resistance and editor of Combat, then an important underground newspaper. Camus was always very active in the theater, and several of his plays have been published and produced. His books, including The Stranger, The Plague, The Fall, Exile and the Kingdom, and The Rebel, as well as his plays, have assured his preeminent position in modern French letters. In 1957 Camus was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. His sudden death on January 4, 1960, cut short the career of one of the most important literary figures of the Western world when he was at the very summit of his powers.

ALSO BY ALBERT CAMUS

Awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1957

Notebooks 19421951

(Carnets, janvier 1942mars 1951) 1965

Notebooks 19351942

(Carnets, mai 1935fvrier 1942) 1963

Resistance, Rebellion, and Death

(Actuellesa selection) 1961

The Possessed (Les Possds) 1960

Caligula and Three Other Plays (Caligula, Le Malentendu, Ltat de sige, Les Justes) 1958

Exile and the Kingdom (LExil et le Royaume) 1958

The Fall (La Chute) 1957

The Rebel (LHomme Rvolt) 1954

The Plague (La Peste) 1948

The Stranger (Ltranger) 1946

SECOND VINTAGE INTERNATIONAL EDITION, NOVEMBER 2018

Copyright 1955, and copyright renewed 1983, by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in France as Le Mythe de Sisyphe. Copyright 1942 by Librairie Gallimard. Originally published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, in 1955.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage International and colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress.

Vintage International Trade Paperback ISBN9780525564454

Ebook ISBN9780525567004

Cover design by Helen Yentus

www.vintagebooks.com

v5.3.2

a

PREFACE

F OR ME The Myth of Sisyphus marks the beginning of an idea which I was to pursue in The Rebel. It attempts to resolve the problem of suicide, as The Rebel attempts to resolve that of murder, in both cases without the aid of eternal values which, temporarily perhaps, are absent or distorted in contemporary Europe. The fundamental subject of The Myth of Sisyphus is this: it is legitimate and necessary to wonder whether life has a meaning; therefore it is legitimate to meet the problem of suicide face to face. The answer, underlying and appearing through the paradoxes which cover it, is this: even if one does not believe in God, suicide is not legitimate. Written fifteen years ago, in 1940, amid the French and European disaster, this book declares that even within the limits of nihilism it is possible to find the means to proceed beyond nihilism. In all the books I have written since, I have attempted to pursue this direction. Although The Myth of Sisyphus poses mortal problems, it sums itself up for me as a lucid invitation to live and to create, in the very midst of the desert.

A LBERT C AMUS

PARIS

MARCH 1955

CONTENTS

THE MYTH OF SISYPHUS

for

PASCAL PIA

O my soul, do not aspire to

immortal life, but exhaust the limits of the possible.

Pindar, Pythian iii

THE PAGES that follow deal with an absurd sensitivity that can be found widespread in the ageand not with an absurd philosophy which our time, properly speaking, has not known. It is therefore simply fair to point out, at the outset, what these pages owe to certain contemporary thinkers. It is so far from my intention to hide this that they will be found cited and commented upon throughout this work.

But it is useful to note at the same time that the absurd, hitherto taken as a conclusion, is considered in this essay as a starting-point. In this sense it may be said that there is something provisional in my commentary: one cannot prejudge the position it entails. There will be found here merely the description, in the pure state, of an intellectual malady. No metaphysic, no belief is involved in it for the moment. These are the limits and the only bias of this book. Certain personal experiences urge me to make this clear.

AN ABSURD REASONING

Absurdity and Suicide

T HERE is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy. All the restwhether or not the world has three dimensions, whether the mind has nine or twelve categoriescomes afterwards. These are games; one must first answer. And if it is true, as Nietzsche claims, that a philosopher, to deserve our respect, must preach by example, you can appreciate the importance of that reply, for it will precede the definitive act. These are facts the heart can feel; yet they call for careful study before they become clear to the intellect.

If I ask myself how to judge that this question is more urgent than that, I reply that one judges by the actions it entails. I have never seen anyone die for the ontological argument. Galileo, who held a scientific truth of great importance, abjured it with the greatest ease as soon as it endangered his life. In a certain sense, he did right. That truth was not worth the stake. Whether the earth or the sun revolves around the other is a matter of profound indifference. To tell the truth, it is a futile question. On the other hand, I see many people die because they judge that life is not worth living. I see others paradoxically getting killed for the ideas or illusions that give them a reason for living (what is called a reason for living is also an excellent reason for dying). I therefore conclude that the meaning of life is the most urgent of questions. How to answer it? On all essential problems (I mean thereby those that run the risk of leading to death or those that intensify the passion of living) there are probably but two methods of thought: the method of La Palisse and the method of Don Quixote. Solely the balance between evidence and lyricism can allow us to achieve simultaneously emotion and lucidity. In a subject at once so humble and so heavy with emotion, the learned and classical dialectic must yield, one can see, to a more modest attitude of mind deriving at one and the same time from common sense and understanding.