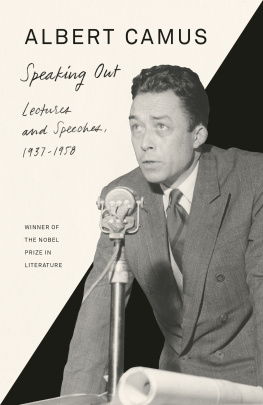

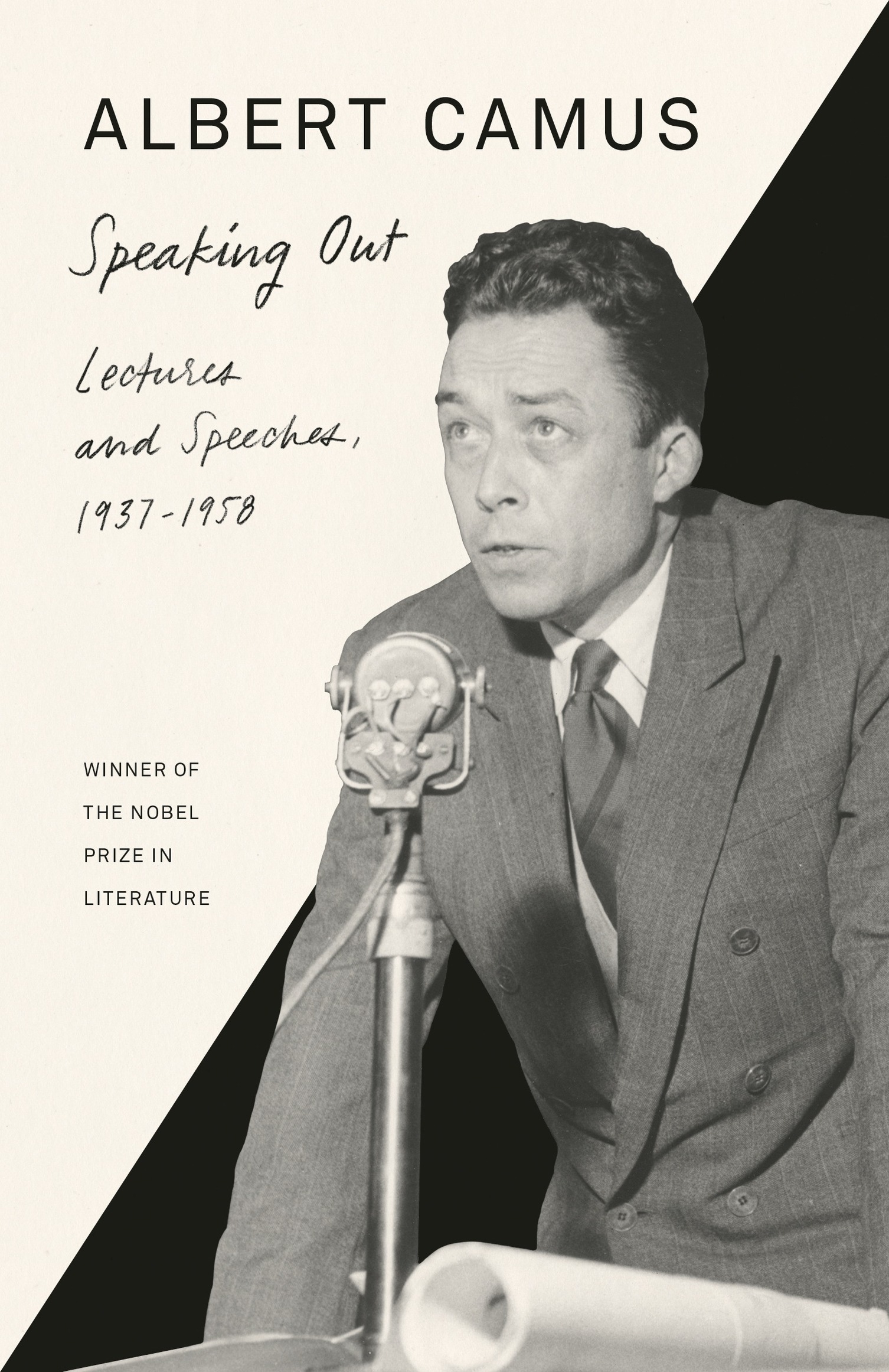

Albert Camus

Speaking Out

Albert Camus was born in Algeria in 1913. He spent the early years of his life in North Africa, where he became a journalist. During World War II, he was one of the leading writers of the French Resistance and editor of Combat, an underground newspaper he helped found. His fiction, including The Stranger, The Plague, The Fall, and Exile and the Kingdom; his philosophical essays, The Myth of Sisyphus and The Rebel; and his plays have assured his preeminent position in modern letters. In 1957, Camus was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. On January 4, 1960, he was killed in a car accident.

Also by Albert Camus

Caligula and Three Other Plays

Committed Writings

Create Dangerously

Exile and the Kingdom

The Fall

The Myth of Sisyphus

Personal Writings

The Plague

The Possessed

The Rebel

The Stranger

A VINTAGE INTERNATIONAL ORIGINAL, FEBRUARY 2022

English-language translation and additional notes copyright 2021 by Quintin Hoare

Foreword copyright 2017 by ditions Gallimard

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in France as Confrences et discours,19361958 by ditions Gallimard, Paris, in 2017. Copyright 2006, 2008, 2017 by ditions Gallimard. This translation originally published in Great Britain by Penguin Classics, an imprint of Penguin Press, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., London, in 2021.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage International and colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress.

Vintage International Trade Paperback ISBN9780525567233

Ebook ISBN9780525567240

Cover design by Stephanie Ross

Cover photograph Daniel Walland/Universal History Archive/Getty

www.vintagebooks.com

ep_prh_6.0_139149577_c0_r0

Contents

Foreword

This volume brings together the thirty-four known texts of public statements by Albert Camus, concluding with the unpublished transcript of his speech at the November 13, 1958, Algerian Club dinner in Paris. Apart from his 1937 talk The New Mediterranean Culture, these speeches and lectures were delivered after the Second World War. By then, the fame of the novelist, essayist, playwright and editorialist meant that his viewpoint on the state of the world and the public mood was regularly sought and awaited, both in France and abroad.

However, Camus was not at heart a lecturer, a role that exposed him to the risk of having to pronounce on subjects about which he felt he had neither the competence nor the legitimacy to speak. Im not old enough for lectures, he warned in 1946. Despite his misgivings, public statements were to be one of the chosen forms of his political commitment, involving both testimony and polemic.

In none of the texts in the current volume does the writer evoke or quote any of his works or his fictional characters, as if the experience of the creator had little in common with that of the occasional orator. Yet the question of the artists commitment remains at the heart of these platform pronouncements, from The Crisis of Man (delivered in New York, 1946) to the famous speeches in Sweden (Stockholm and Uppsala, 1957). There is no rupture, he seems to tell us, between the commitment of the citizen and that of the writer, inasmuch as the latter, through his work, seeks to keep as close as possible to a human truth more than ever exposed to terror, to lies, to bureaucratic and ideological abstraction, to injustice. The artist distinguishes where the conqueror evens out. The artist who lives and creates at the level of the flesh and passion knows that nothing is simple and the other exists (see ). And he knows the flesh may be happy or unhappy.

The Camusian revolt is situated at the heart of the absurd, in the simultaneous recognition of common destiny and individual freedom. That is what underpins these public pronouncements. From one lecture to the next, Camus makes explicit and manifest his commitment as a man who aims to restore voice, face and dignity to those who have been stripped of them by half a century of sound and fury, in which the misuse of words and the excess of ideas have made man a wolf to himself.) and suppress the poison of death within ourselves. Such is the generational experience to which the writer here bears witness.

There is a Crisis of Man which needs to be registered and explained. And the speaker sets about this here, repeatedly formulating and reformulating its causes and symptoms. But most important is to find a remedy for it, with the hope that humankind can recover, of his own accord, that taste for man without which the world will never be anything but a vast solitude (see ). Artists and writers have their role to play, modest but necessary.

For Camus, man has a vocation that consists in opposing the worlds unhappiness in order to diminish its intensity, within each individuals particular limits. Camuss authority as an intellectual and his specific journey give his words a special audience, in a world that has already become globalizedparticularly under totalitarian and imperialist pressures. He does not limit his commitments to national frontiers: Europe is at the heart of his concerns, indeed his indignation, when it is the Europe of Franco and meets with no condemnation. He also takes to the rostrum when his brethren in Eastern Europe are subjected to an insane totalitarianism, crushing all liberties with the utmost contempt for human individuality and justice.

What is at stake is not just culture but civilization, and the fraternal sentiment that unites individuals in the struggle against their destiny. Thereby is traced an ethics for himself: this vocation of man is an apprenticeship, a discipline, played out daily and throughout life: I prefer committed men to committed literature, he wrote in his Notebooks. Courage in ones life and talent in ones work, thats not too bad.

Quintin Hoare

Indigenous Culture: The New Mediterranean Culture

1937

A member of the Parti Communiste Algrien ( PCA ) since late summer 1935, Albert Camus involved himself in cultural action by founding the Thtre du Travail, a company that he managed at the same time as being a scriptwriter, director and actor. Meanwhile, he became general secretary of the Algiers Cultural Center, which organized cinema shows, concerts and lectures. It was at the inauguration of this body on February 8, 1937, that Camus, then twenty-two years old, delivered the following lecture. The text was published in the first issue of the Cultural Centers bulletin,