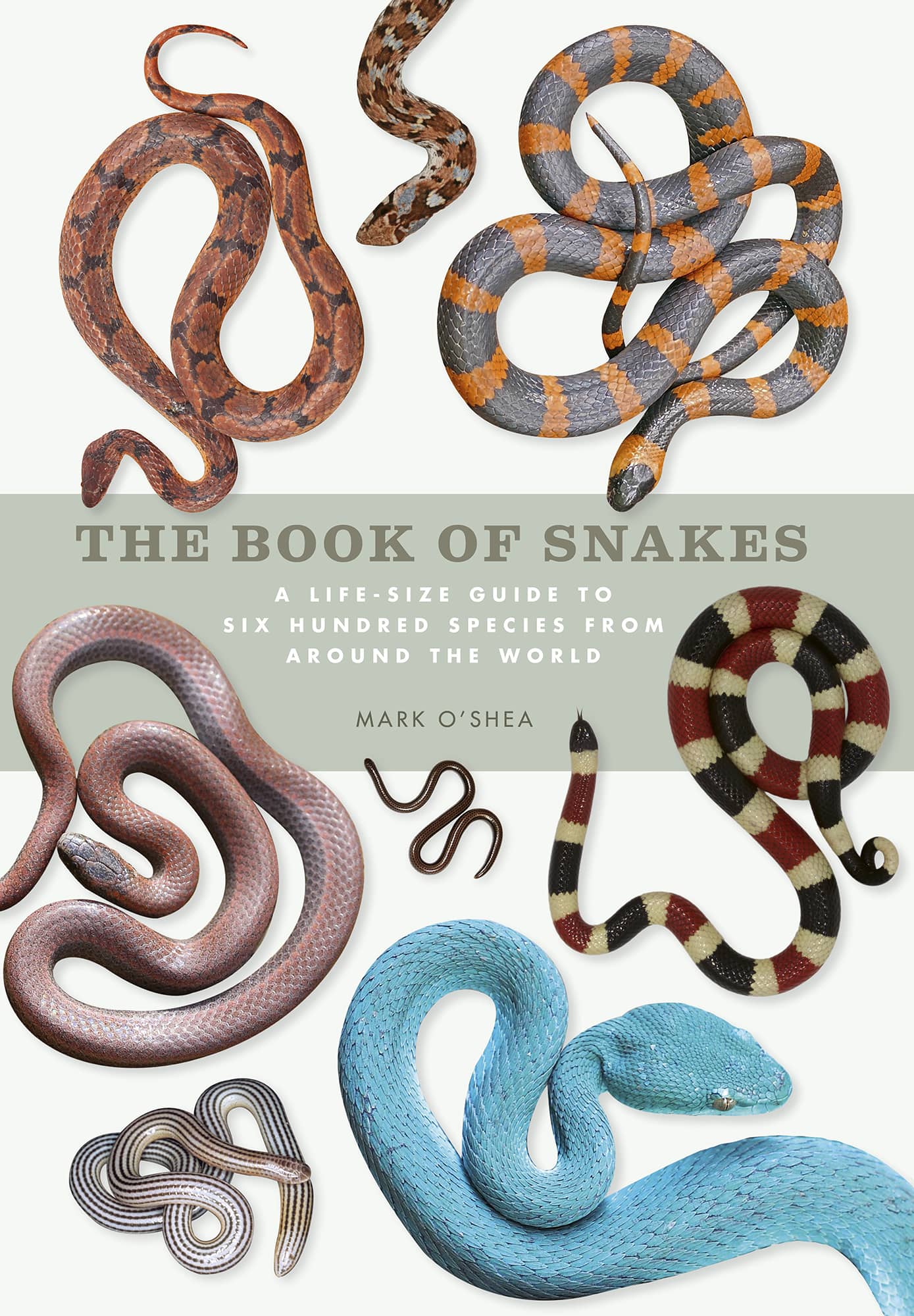

THE BOOK OF SNAKES

A LIFE-SIZE GUIDE TO SIX HUNDRED SPECIES FROM AROUND THE WORLD

MARK OSHEA

MARK OSHEA is a herpetologist, television presenter, zoologist, author, photographer, and lecturer. He is Professor of Herpetology at the University of Wolverhampton, UK and the Consultant Curator of Reptiles at West Midland Safari Park in the UK. He has been involved with snakes for more than five decades, initially keeping them in captivity, but gradually moving to become a professional herpetologist without a personal collection. Between 1999 and 2003 Mark presented four seasons of the internationally acclaimed OSheas Big Adventure for Animal Planet, co-produced with the UKs Channel 4 as OSheas Dangerous Reptiles. He has now presented almost forty documentaries including films for Discovery Channel, ITV, and the BBC. Mark has conducted herpetological fieldwork, or made films, in almost forty countries worldwide, on every continent except Antarctica. During 198788 he spent seven months as the herpetologist on the Royal Geographical Society Marac Rainforest Project in Roraima, Brazil. He also ran herpetological projects on six expeditions for Operation Raleigh, Raleigh Executive, and Discovery Expeditions, during the 1980s90s. He has made ten expeditions to Papua New Guinea (PNG) since 1986 and has worked on a long-term snakebite research project there, initially for Oxford University and the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, and since 2006 for the Australian Venom Research Unit, University of Melbourne. More recently he has worked on a snakebite project in Myanmar for the University of Adelaide. Since 2009 he has also worked as co-leader of a team working out of a Californian community collegethe team has documented the first comprehensive herpetological survey of Timor-Leste, Asias newest country. With ten phases of the project completed, they have documented around 70 species, 2025 of them new to science. Marks specialist area is the snake fauna of New Guinea and Wallacea, and his research takes him to natural history museums worldwide to examine snake specimens collected as far back as the nineteenth century. Mark has described a number of new snake species from PNG. In 2000 Mark received one of only eight Millennium Awards for services to exploration from the British Chapter of the Explorers Club of New York, Marks award being for zoology. In 2001 the University of Wolverhampton awarded him an honorary Doctor of Sciences degree for his contributions to herpetology. He is the author of five books, including A Guide to the Snakes of Papua New Guinea (1996), of which he is currently working on the second edition. He has also written numerous articles and scientific papers. He lives in Shropshire, England, 15 miles from the birthplace of Charles Darwin.

INTRODUCTION

Snakesalmost everybody has an opinion about them, and often those opinions are extremely polarized, with people either fearing snakes or being fascinated by them. The sinuous movements of a snakes body, the oil-on-water effect of its iridescent scales, the hypnotic movements of its elevated head, the unblinking gaze, the continually flickering tongue, and often the serpents totally unexpected and unannounced appearance, are all factors that play into its ability to convey both beauty and menace in a single tongue-flick.

It is no surprise that the snake has touched so many societies throughout history and been included in countless cultural and religious stories. By shedding its skin, it may be seen as a symbol of renewal and long life, but at the same time it is the bringer of death. It is likely that since humans first walked upon the Earth, the snake has held them in its thrall, an ever-present danger in the shadows, hidden in leaf litter, reaching out from a leafy bough, or lurking beneath dappled waters.

So, why do so many people shudder at the very word snake? Obviously, one of the reasons people fear snakes is perfectly reasonable and naturalsome snakes can, and do, kill humans. Worldwide, up to 125,000 lives are lost through snakebites every year. But, putting this into perspective, figures extrapolated from World Health Organization data suggest that 1.25 million people may have died in road-traffic accidents in 2015, ten times as many as were killed by snakes over a similar 12-month period.

A venomous serpent striking from a leafy bough probably epitomizes the worst nightmare for many people. Yet this Great Lakes Bushviper (Atheris nitschei) is actually a highly specialized and wonderfully adapted predator of mammals, lizards, or frogs that only uses its venom in defense when it feels truly threatened.

A hooding Egyptian Cobra (Naje haje) an iconic image, yet the purpose of the hood is to warn potential attackers that the cobra will defend itself if necessary; it is trying to avoid confrontation, not provoke it.

There are a little over 3,700 living snake species known to science. They exhibit a truly amazing diversity of shape, size, color, pattern, and natural history. In The Book of Snakes, I will introduce the reader to 600 species, almost one in six of all snakes known. For those who are unfamiliar with snakes, I aim to dispel myths and bring enlightenment and understanding about one of the most maligned groups of animals on the planet. For those who are already snake aficionados, I hope to introduce rare or elusive species that may have previously passed beneath their radar.

In selecting which 600 species to feature in The Book of Snakes, I went for diversity, including many of the familiar names, both the popular, inoffensive snakes kept as pets, and the infamous, highly venomous species that claim lives. But I also wanted to illustrate less well-known species, from remote islands, cold mountains, arid deserts, verdant rainforests, and the open oceanssnakes with unique lifestyles or diets, and each with its own interesting story to tell. Some species are so rare that we struggled to find a single photograph to represent them. And that was the one hard-and-fast rule: if no image was available or of sufficient quality to represent the species at life size, then that species did not make the book. However, thanks to the many excellent photographers who have contributed images, we lost fewer than 30 species from the original selection.

I hope that The Book of Snakes will appeal to both armchair naturalists and experienced fieldworkers alike, but particularly that it will inspire budding herpetologists of future generations to respect, study, and protect snakes.