Copyright 2019 by Kimberly Mehlman-Orozco

Foreword 2019 by Chris Sampson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

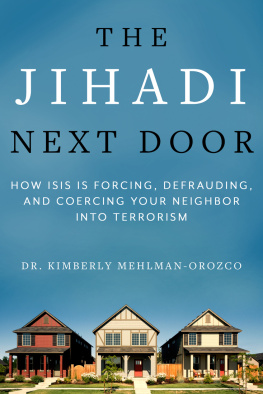

Cover design by Brian Peterson

Cover photo credit: iStockphoto

ISBN: 978-1-51073-286-5

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-51073-287-2

Printed in the United States of America

For all the parents who have lost a child to terrorism.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Why would anyone join ISISthe terrorist offspring of al-Qaeda?

While much has been written on the roots of the organization and the violent tactics used by the group, more understanding is needed on what brought these terrorists to the world stage. People are not recruited to commit murder simply as a result of watching a propaganda video or from a belief in a particular religion. It is a process known as radicalization.

By selectively targeting vulnerable individuals, terrorists use a series of techniques to lower the recruits inhibitions, increase a strong sense of grievance, and build a feeling of community. To understand this process, we look at cases and testimony from those who have taken this path to destruction and learn from the choices they made. In this book, Dr. Kimberly Mehlman-Orozco applies her experience in criminology to lay out an understanding of what it takes to draw people from the fabric of society into a world of extremism and, ultimately, terrorism.

Understanding these lures assists counterextremist efforts in exposing the lies used by recruiters. Targeted conscripts are pulled in by promises of being made heroesof being useful and relevant. Recruits come from various backgrounds and many seem surprising at first glance.

For example, Colleen LaRose of Detroit became a high-profile recruit to ISIS, yet her background seemed at odds with what many people conceived as the type of person who would join the terrorist group. However, as the book will show, she had all the conditions necessary to be at risk of radicalization. All her recruiter needed to do was give her a role that she had failed to achieve in her life thus far. She had an opportunity to become someone elsesomeone important, valued, and cherished. With the terrorists who recruited her, LaRose felt her abusive upbringing, repeated mistreatment, failed relationships, and drug-addicted life could be things of the past. She reinvented herself as Fatima LaRosean aspiring suicide bomber before becoming internationally notorious as Jihad Jane.

This pattern isnt isolated in one country, either. The Jihadi Next Door highlights stories of men and women, young and old, from around the world, who joined ISIS based on promises of change, community, and heroic adventure. Despite many differences on the surface, most recruits shared common characteristics in their lack of social acceptance, engagement, and successes.

The range of their personal attributes reflected a clear pattern of ISIS targeting. They wanted to bring in people from the Muslim world as part of their effort to hijack the religion. They sought to recruit people from outside the Muslim world who didnt understand the Arabic language, the deep roots of the Islamic culture, or the religion so they could carry out their death cult view of Islam. They sought out people from various sectors of society to fill organizational needs. For grunt fighters, ISIS worked to lure young men who would fight to the death for their so-called caliphate. For breeding another generation, they sought women who desired husbands and a sense of fulfillment. To lure these groups in, they targeted recruits who would focus on promises of brides and husbands. They sought bright, computer-savvy people like Junaid Hussain and Siful Sujan from the UK to hack and engage in social engineering. They pursued people in marginalized groups of societies and fed their need to belong.

As the caliphate crumbled underneath them in recent years, ISIS fanned out into other fragmented countries that were at the outer perimeter of their reach. After they lost territory in Syria and Iraq they retreated to failed countries like Yemen, Libya, and Afghanistan. ISIS efforts in Boko Haram, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Philippines remained ongoing crises even after the losses in Syria and Iraq. It must be stated that though ISIS failed to hold its grip on Syria and Iraq in the second half of 2018, they still have an estimated thirty thousand fighters in the organization at the time of this publication.

Terrorists thrive on resentment and ignorance. The examples in this book are a guide for those who wish to understand the inception of extremism through the stages of radicalization to the acts of terror, which can be equally applied to other groups. Gangs, white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and other extreme political organizations follow many of the same patterns as weve seen used by ISIS. The Jihadi Next Door does well at covering specific examples of recruitment and can serve future scholars as a window into the radicalization process, which neednt be limited to ISIS.

Chris Sampson

Terrorism Analyst

Coauthor of Hacking ISIS: How to Destroy the Cyber Jihad

AUTHORS NOTE

You will soon realize that the title of this book is paradoxical, which was my intention. I will argue that the term jihadi should not be used interchangeably with the nouns terrorist and extremist.

Jihad is a religious word, which is referenced in the Quran. It literally means a struggle or effortto live out the Muslim faith as well as possible, to build a good Muslim society, and to defend Islam, with force if necessary, but with rules of engagement.

Terrorists do not engage in religiously sanctioned or legal warfare with proper rules of engagement; they are criminals who commit horrific acts of violence with cowardice and deceit. Their leadership is truly motivated by money and power, not religion. Therefore, despite their self-proclamations, I try not to describe them as jihadists or as engaging in jihad. Instead, I have attempted to more accurately refer to them as terrorists or irjafiyyun (singular irjafi ), extremists, and criminals.

Likewise, a mujahid is someone who engages in jihad, which terrorists dont do; and a martyr is someone who is killed because of their religious beliefs. Terrorists are suicide bombers, not martyrs.

Although this may seem like I am quibbling over semantic distinction for the sake of political correctness, I will argue that this confounding use of language reflects a larger issue that undermines the efficacy of counterterrorism interventions.

Words matter, especially because:

A lie told often enough becomes truth.