Contents

Page List

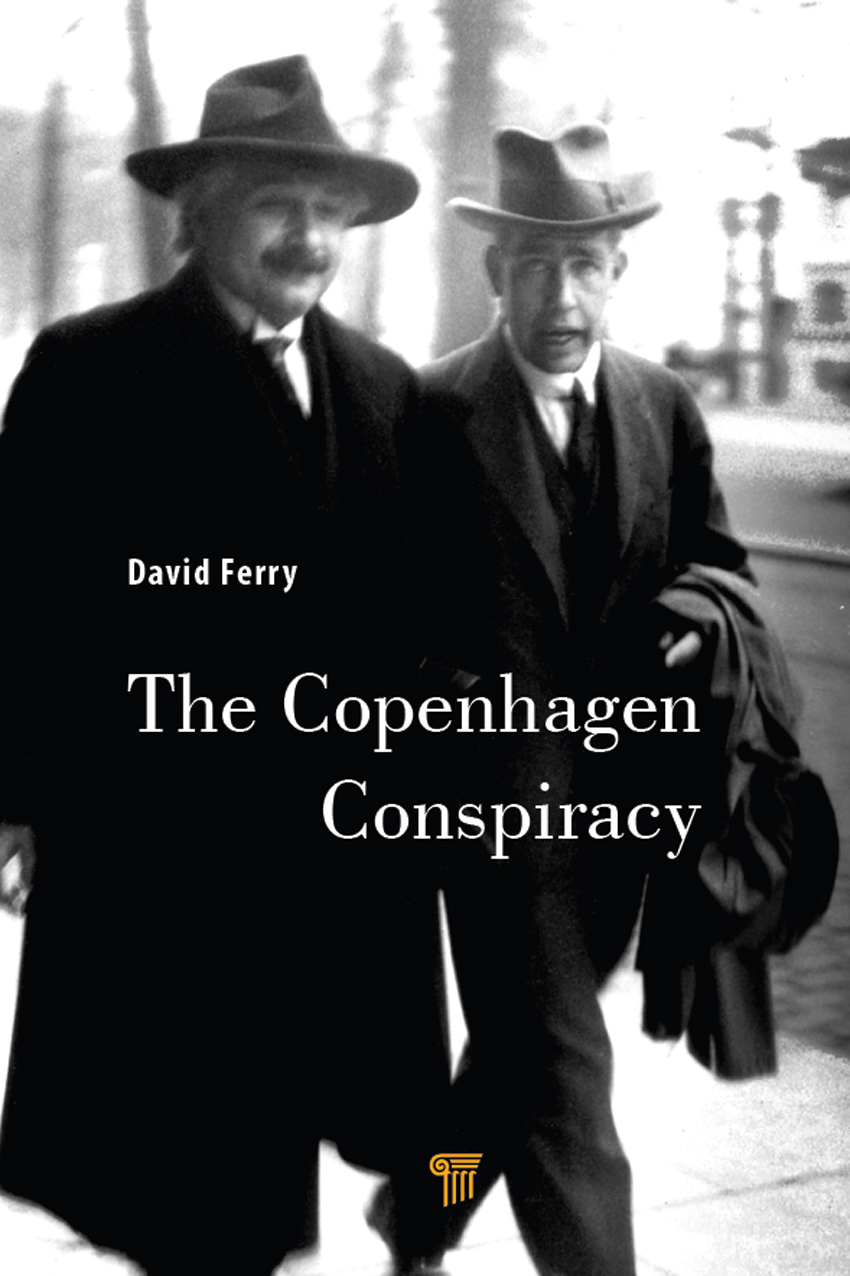

The Copenhagen Conspiracy

The Copenhagen Conspiracy

David Ferry

Published by

Pan Stanford Publishing Pte. Ltd.

Penthouse Level, Suntec Tower 3

8 Temasek Boulevard

Singapore 038988

Email:

Web: www.panstanford.com

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The Copenhagen Conspiracy

Copyright 2019 Pan Stanford Publishing Pte. Ltd.

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission from the publisher.

For photocopying of material in this volume, please pay a copying fee through the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. In this case permission to photocopy is not required from the publisher.

ISBN 978-981-4774-75-8 (Hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-351-20723-2 (eBook)

Contents

As the nineteenth century was drawing to a close, there occurred a rash of technological breakthroughs that would ultimately presage the information revolution a century later. There was Bells telephone in the 1870s, Edisons carbon microphone and incandescent light bulb just before 1880, development of early automobiles in the 1880s, Marconis wireless telegraph in the 1890s, and many early experiments in flight which led to the Wright brothers in 1903. In fact, technology had progressed so rapidly that Albert Michelson, perhaps the preeminent American scientist of the period, is said to have remarked in 1894 that the grand underlying theories of science have been firmly established and the future truths of science are to be looked for in small changes to known values. It was even suggested to close the Patent Office. Yet, at the close of the nineteenth century, we stood on the threshold of one of the greatest periods of science, in which the entire world and understanding of science would be shaken to the core and greatly modified. This explosion of knowledge led ultimately to that same information revolution that we live in today. Planck and Einstein showed that light was not continuous, but made of small corpuscles that today we call photons. Einstein changed the understanding of mechanics with relativity theory, airplanes became conceivable, radio and television blossomed, and the microelectronics industry, which drives most of modern technology, came into being. New areas of science were greatly expanded and developed, and one of these was quantum mechanics, which is the story to be told here.

What is interesting is that quantum mechanics may well be the last area of physical science that clings to the nineteenth-century views of Ernst Mach. Most people know of him from the Mach number, the speed of an aircraft relative to the velocity of sound. Fewer know that he was the de facto leader of the Viennese philosophy community in the latter parts of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. One can perhaps summarize his philosophy by saying that he did not believe in atoms because he couldnt see them. This view stemmed from a belief that reality was contingent on actual observations or conscious awareness of the event. It is perhaps best described by the elementary school puzzle as to whether a tree, falling in the forest, makes a sound if no one is there to hear it. Perhaps it is worth considering this. One could of course put a microphone in the forest to record any events that happened. Then, does the reality of the tree arrive only when we listen to the recording. Or, indeed, does the recording only become real when we listen to it. I suspect that rational people would decide otherwise. Yet, in quantum mechanics, this is still the accepted interpretation of the field.

It is important to understand that I am using Mach as a symbol of what has been called by some as positivism, although it may better be referred to as negativism when we discuss the theoretical foundations of modern physics. I am also fully aware that there were a great number of philosophers of science who contributed to this, as well as many more modern ones who have modified it. Nevertheless, I will still use Mach as the paradigm. The reader will find citations to Philipp Frank as well, and I am fully aware that he was one of the founders of the Vienna Circle, a group of Austrian philosophers and physicists, who often were more Machist than Mach himself. It also is true that a great percentage of scientists at the start of the twentieth century actually were infected with the Mach point of view. There certainly was an ongoing dispute between the positivists and the more realistic views of many physicists. The rise of quantum mechanics occurred in the midst of these disputes. Einstein himself is said to have been a devotee when young. But he rapidly realized that his view of reality could be explained and advanced with the development of true theory, such as relativity, particularly special relativity. In Machs view, such a theory, without experimental observation, could not be a description of reality. Yet, Einsteins curved space and gravity waves, Diracs positrons, and even Higgs boson were all accepted by most of science before the confirming experiments were ever performed. Its true that Diracs prediction lay in the field of quantum mechanics, but it was not accepted by some until the experimental observation of the positron was made, and they could no longer push it aside.

As remarked above, science and technology progressed tremendously in the 1880s. In technology, this led to an economic boom, but, as with many such booms, it became overextended. Financial problems in Argentina (whats new?) and the failure of several American railroads led to the financial crash of 1893. In science, the success of Boltzmann and statistical physics was met with the antagonism of Mach and his followers, leading to what I will call the religion of positivism. This continued to grow into the new century with the founding of the Vienna circle, and similar efforts elsewhere. Perhaps this rise should be called the intellectual crash of the 1890s.

The high priest of this religion in quantum mechanics was Neils Bohr, and his viewpoint could be reinforced as most young scientists of the period felt a need to spend time in Copenhagen. He was a leader, along with his disciples, in the formulation of quantum mechanics and thus built this view into the underlying philosophy of quantum mechanics. Thus the religion was passed on to each new disciple and bred into the leadership of the coming quantum revolution. One view is, Here I only note that those who accept Bohrs way of thinking speak of the spirit of Copenhagen while those who are critical speak of the Copenhagen orthodoxy. Nevertheless, these were all affected by an intense subjugation to Bohrs pressure, which some have viewed, using a post-WW2 phrase, as brainwashing.

There are some who would say that Bohr set back the real understanding of quantum mechanics by half a century. I believe they underestimate his role, and it may be something more like a full century. Whether we call it the Copenhagen interpretation or the Copenhagen orthodoxy, it is the how for the continuing mysticism provided by Mach that is still remaining in quantum mechanics. It is not the why. Why it perseveres and