Table of Contents

Copyright 1992 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Sixth printing, 1998

Excerpt from Mr. Cogito and the Imagination on page xi 1985 by Zbigniew Herbert, translation 1985 by John Carpenter and Bogdana Carpenter. From Report from the Besieged City and Other Poems by Zbigniew Herbert. First published by The Ecco Press. Reprinted by permission.

First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 1994

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

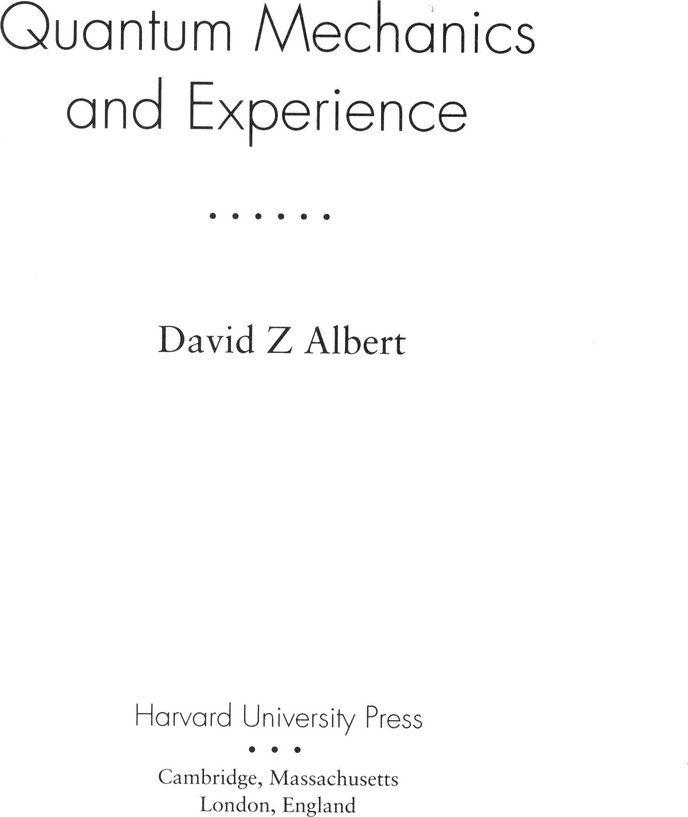

Albert, David Z

Quantum mechanics and experience / David Z Albert.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-674-74112-9 (alk. paper) (cloth)

ISBN 0-674-74113-7 (pbk.)

1. Physical measurements. 2. Quantum theory. I. Title.

QC39.A4 1992

530.16dc20

92-30585

CIP

To my wife, Orna

Preface

This book was written both as an elementary text and as an attempt to add to what we presently understand, at the most advanced level, about what seems to me to be the central difficulty at the foundations of quantum mechanics, which is the difficulty about measurement .

The first four chapters are a more or less straightforward introduction to that difficulty: Chapter 1 is about the idea of superposition, which is what most importantly distinguishes the quantum-mechanical picture of the world from the classical one, and which is where everything thats puzzling about quantum mechanics comes from. Chapter 2 sets up (in a way that presumes nothing at all, insofar as I understand how to do that, about the mathematical preparation of the reader) the standard quantum-mechanical formalism and outlines the conventional wisdom about how one ought to think about that formalism. Chapter 3 is about the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen argument and how that argument was stunningly undercut by Bell (and it is urged there, by the way, that what Bells discovery actually amounts to is very frequently misunderstood; it is urged that Bell discovered something not merely about hidden-variable theories but also about quantum mechanics, and also about the world ). Finally, Chapter 4 explicitly sets up the measurement problem.

The rest of the book (which is the bulk of the book) is taken up with investigations of those ideas about what to do about the measurement problem which seem to me to have some possibility of being right: Chapter 5 is an account and a critique of the idea of the collapse of the wave function (with a detailed discussion of the recent breakthrough of Ghirardi, Rimini, and Weber). Chapter 6 is about a certain very confused but nonetheless (I want to argue) very interesting tradition of thinking about the measurement problem which is (misleadingly) called the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. Chapter 7 is about a completely deterministic replacement for quantum mechanics due to de Broglie and Bohm and Bell. And Chapter 8 is about what the mental lives of sentient observers can potentially be like, if either one of the proposals discussed in Chapters 6 and 7 should actually happen to pan out.

Lots of people helped me out with this. Let me mention a few.

Barry Loewer is the one who first suggested that this book be written, and he has (astonishingly) been willing to spend many hours of his time talking about it with me, and many of the original ideas in it are (as the reader will learn from the references) partly his; and if not for all that, it simply could not have come into being.

Ive learned a great deal about the foundations of quantum mechanics from innumerable conversations, over many years, with (first and foremost) Yakir Aharonov, and also with Hilary Putnam, David Deutsch, Irad Kimchie, Marc Albert, Gary Feinberg, Lev Vaidman, Sidney Morgenbesser, Isaac Levi, Shaughn Lavine, and Jeff Barrett, and also with students in some classes Ive taught.

I am much indebted to Andrea Kantrowitz for doing such a great job with the illustrations; and I am thankful to Lindsay Waters and Alison Kent and especially Kate Schmit of Harvard University Press, without whose help and understanding this would have been a much less valuable book.

And maybe it ought to be mentioned that this book was written in the hope of finally being able to explain these matters to the reasonable satisfaction of my uncle, the physicist Arthur Kantrowitz, who first got me interested in science.

a bird is a bird

slavery means slavery

a knife is a knife

death remains death

Superposition

Heres an unsettling story (the most unsettling story, perhaps, to have emerged from any of the physical sciences since the seventeenth century) about something that can happen to electrons. The story is true. The experiments I will describe have all actually been performed.

The story concerns two particular physical properties of electrons which it happens to be possible to measure (with currently available technology) with very great accuracy. The precise physical definitions of those two properties dont matter. Lets call one of them the color of the electron, and lets call the other one its hardness.

It happens to be an empirical fact that the color property of electrons can assume one of only two possible values. Every electron which has thus far been encountered in the world has been either a black electron or a white electron. None have ever been found to be blue or green. The same goes for hardness. All electrons are either soft ones or hard ones. No one has ever seen an electron whose hardness value was anything other than one of those two.

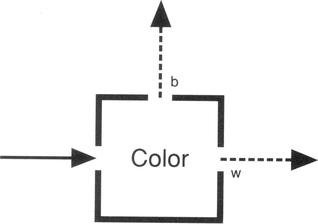

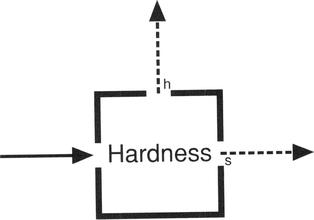

Its possible to build something called a color box, which is a device for measuring the color of an electron and which works like this: The box (see figure 1.1) has three apertures. Electrons are fed into the box through the aperture on the left, and every black electron fed in through that aperture exits (along the indicated dashed line) through the aperture marked b , and every white electron fed in through that aperture on the left exits through the aperture marked w ; and so the color of any electron which is fed in through that aperture on the left can later be inferred from its final position. Its possible to build hardness boxes too, and they work in just the same way (see figure 1.2).

Measurements with hardness and color boxes are repeatable, which is something weve grown accustomed to requiring, by definition, of a good measurement of a bona fide physical variable. If, say, a certain electron is measured with a color box to be black, and if that electron (without having been tampered with in the meantime) is subsequently fed into the left aperture of another color box, then that electron will with certainty emerge from that second color box through the b aperture as well. The same goes for white electrons, and the same goes (with hardness boxes) for hard and soft electrons too. All that can be (and has been) confirmed by means of tests with those boxes.

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.2

Now, suppose that it occurs to us to be curious about the possibility that the color and hardness properties of electrons might somehow be related to one another. One way to look for such a relation might be to check for correlations between the values of the hardness and color properties of electrons. Its easy to check for correlations like that with our boxes; and it turns out (once the checking is done) that no such correlations exist. Of any large collection of, say, white electrons, all of which are fed into the left aperture of a hardness box, precisely half emerge through the hard aperture, and precisely half emerge through the soft one. The same goes for black electrons fed into the left aperture of a hardness box, and the same for hard or soft ones fed into the left apertures of color boxes. The color (hardness) of an electron apparently entails nothing whatever about its hardness (color).