About the Book

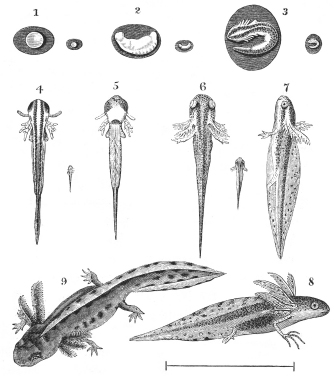

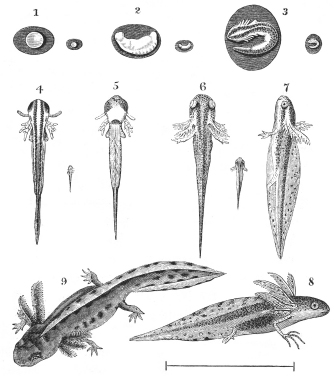

As a boy, Richard Kerridge loved to encounter wild creatures and catch them for his back-garden zoo. In a country without many large animals, newts caught his attention first of all, as the nearest he could get to the African wildlife he watched on television. There were Smooth Newts, mottled like the fighter planes in the comics he read, and the longed-for Great Crested Newt, with its huge golden eye.

The gardens of Richard and his reptile-crazed friends filled up with old bath tubs containing lizards, toads, Marsh Frogs, newts, Grass Snakes and, once, an Adder. Besides capturing them, he wanted to understand them. What might it be like to be cold blooded, to sleep through the winter, to shed your skin and taste wafting chemicals on your tongue? Richard has continued to ask these questions during a lifetime of fascinated study.

Part natural-history guide to these animals, part passionate nature writing, and part personal story, Cold Blood is an original and perceptive memoir about our relationship with nature. Through close observation, it shows how even the suburbs can seem wild when we get close to these thrilling, weird and uncanny animals.

About the Author

Richard Kerridge leads the MA in Creative Writing at Bath Spa University. His essays have been published in Granta and Poetry Review, and he has twice won the BBC Wildlife Award for Nature Writing.

Acknowledgements

Will Francis, my literary agent, saw the potential of this book early on, and encouraged and helped me as the idea took shape. When I began to put short pieces of writing together, he was an exacting reader, with an unerring eye for phrases that were not clear. For that and for his skill at marketing the proposal and negotiating on my behalf, I give him deeply-felt thanks. Clara Farmer has been a superb editor, very precise, full of understanding of what I was doing and expert at helping me get to the finish. I owe her a very great deal. Susannah Otter steered me expertly through my nervous last edits, understanding exactly what was needed. James Jones designed hardback and paperback covers that caught the spirit of the book more exactly than I would have thought possible. My thanks go to all of the team at Chatto and Windus, and to Joe Burgis at Vintage.

Chris Nicholson, Tessa Hadley, Greg Garrard, Paul Evans and Tim Liardet have read sections of the book and given expert and encouraging advice, and, more importantly, have supported me with humour and honest, steadfast friendship. Chris, especially, found many literary leads for me and gave me the frankest of criticism. Kitty (Catharine) Nicholsons astonishing drawings of woodland and heathland micro-landscapes have been an inspiration to my attempts to write about such places. SueEllen Campbell taught me a great deal about how to integrate scientific and personal writing. For twenty years I have benefited enormously from being able to work with students and teachers on the MA in Creative Writing at Bath Spa University. In so many ways that experience has helped me break through into the writing I always longed for. Students there, and tutors such as Richard Francis, Steve May, Colin Edwards, Gerard Woodward and Jeremy Hooker, have shown me so much of what writing involves, and some of it sank in.

Fiona Sampson responded with sharp and sympathetic understanding to a section of the work that she heard me read aloud, and subsequently published part of it in Poetry Review support that was crucial (volume 101:4, winter 2011). An early version of another part appeared in Granta Online (2 December 2011: http://www.granta.com/New-Writing/Our-Adder). Chris Davis, a leader of the Sand Lizard Recovery Programme, gave me an interview that was warm, funny and generous with information. Cate Sandilands gave permission for the quotation in Chapter Two from her memoir/essay Landscape, Memory, and Forgetting (published in Material Feminisms, edited by Stacy Alaimo and Susan Hekman, Indiana University Press, 2008). She also commented usefully on Cold Blood in response to a reading I gave at the conference of the UK and Ireland branch of the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment at the University of Surrey in 2013. ASLE, in both the UK and the USA, has been a steady source of relevant discussion. I have benefited also from the annual scientific meetings organised by the British Herpetological Society, and from passionate debates on Reptiles and Amphibians of the UK, the website set up by Chris Davis (http://www.herpetofauna.co.uk): especially the contributions of Gemma Fairchild and Wolfgang Wster.

Trips to hot reptile and amphibian spots across the UK were supported by Bath Spa University and by the Roger Deakin Award for 2012, given by the Society of Authors. Rees Cox and Helen Fearnley gave me stories about Smooth Snakes and Sand Lizards. Hugh Nicholson took me looking for snakes along Regents Canal. Kate and Robert Rigby were with me on two occasions when I seemed mysteriously to have conjured snakes, one of which I have described in the book. Paul and Shelly allowed me to sit at their dinner table writing frantically for a week, and did their best to help me look for rattlesnakes on the hillside at the bottom of their garden, though I am not sure they hoped as much as I did for success.

Thanks to my parents Paul and Dorothy and my sisters Cathy and Ann. They did not ask to be characters in this book, and my mother and sisters have responded with generous feeling. I hope they see Cold Blood as the loving book I believe it to be. Thanks also to all the friends who had reptile and amphibian adventures with me.

Most of all in a home more dominated by matters reptilian than anyone would have chosen but me thanks to my daughters Lily and Violet for their love and for so much happiness, to Imogen who once came on a reptile expedition at the age of six and screamed when an Adder crossed the path inches from her feet, and to Tracy, for reading chapters in successive versions and giving detailed advice every time. And for her love, patience and belief.

Chapter One

Palmate Newt

IT STARTED WITH a golden newt in a black bog. I was ten.

We were walking on Dartmoor, coming down a heathery slope. I can imagine the kind of day it was. Around us the moor looked beaten up by winter: muddy, uncommunicative, hunkered down into itself. The heather was faded, the bracken collapsed and papery, the grass washed-out, the earth wet. Cold breezes rushed at my face and found a way down the back of my neck. But the sun was out, and around me creatures were coming to life. Chirruping birdsong sprang up and was answered. Bumblebees wobbled into flight, to be snatched by the wind. Spiders scuttled from my feet. A crow called three times, and took off, flapping hard. The gorse bushes were dense with yellow flowers. Around them, in the sun, there was a coconutty warmth.

Our path dropped towards a boggy stream and a bridge of flat stones. Pools glittered there. I ran ahead and lay on the bridge to look into the water. Quietness settled around me. The April sun warmed my back. The stream was shallow here, hardly moving over deep-looking mud. On either side, there was bog, clumps of ribbony brown grass, rising out of black slime. Between them were dark shallow pools. Patches of oily film gleamed on the surface. Tiny beetles raced in circles, catching the light.