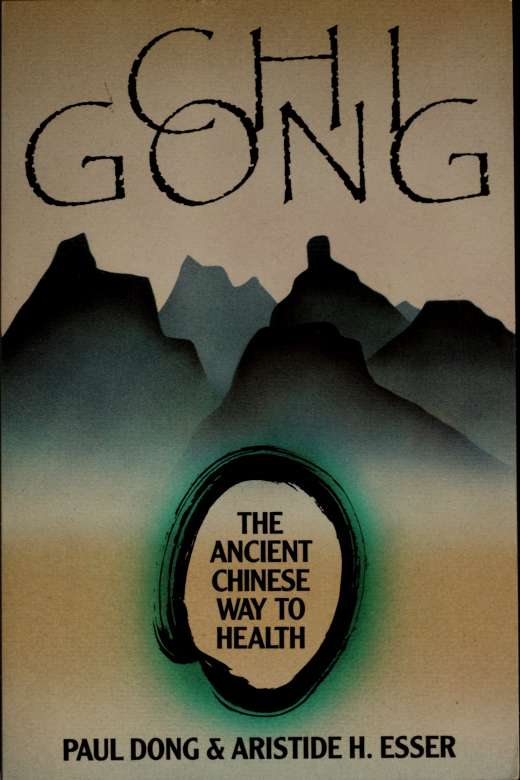

Paul Dong - Chi Gong: The Ancient Chinese Way to Health

Here you can read online Paul Dong - Chi Gong: The Ancient Chinese Way to Health full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1995, publisher: Da Capo Lifelong Books, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Chi Gong: The Ancient Chinese Way to Health

- Author:

- Publisher:Da Capo Lifelong Books

- Genre:

- Year:1995

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Chi Gong: The Ancient Chinese Way to Health: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Chi Gong: The Ancient Chinese Way to Health" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Paul Dong: author's other books

Who wrote Chi Gong: The Ancient Chinese Way to Health? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Chi Gong: The Ancient Chinese Way to Health — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Chi Gong: The Ancient Chinese Way to Health" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

"Be imperturbable and the true chi will come to you; concentrate the inner spirit and well-being will follow.'

The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine

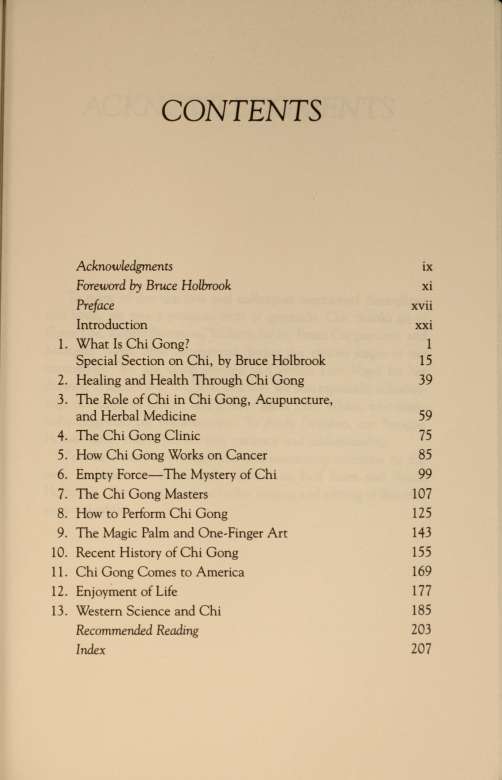

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To many of our teachers and colleagues mentioned throughout this book, we owe a personal debt of gratitude. Our thanks go to Cyms Lee, Robert Sampson, William Sacks, James Cappuccino, and Marcello Tmzzi, who commented during the various stages of our manuscript. We are much obliged to Cynthia Lott Vogel for her drawing of figures 3-1, 3-2, 8-4, and 9-4. We also especially acknowledge our editorial adviser and literary agent John White, who originally suggested our collaboration. To Andy DeSalvo, our Paragon House editor, thank you for your patience and understanding.

For their early encouragement and unstinting attention to the work at hand, we must, too, thank Ada Re if Esser and Bruce Holbrook. Their contributions to the writing and editing of this text are invaluable.

FOREWORD

by Bruce Holbrook

Currently there is a potentially revolutionary transmission of Chinese medical ideas, practices, and materials to Europe and North America. This book focuses on what may be the most crucial concept to the success or failure of the West s attempt to adopt and make good use of these treasures. What I would like to say should prove useful to the reader who is not familiar with both the Chinese and American poles of this cultural transmission.

I began practicing chi gongthe cultivation and deliberate control of a higher form of vital energyin 1969 in Taiwan, which was at that time the sector of China least transformed by Western civilization and hosting the greatest number per capita of traditional physicians and martial artists from all of the Chinese provinces. My teachers through 1974, Li Ts'an, Hsu Bei-Ying, and Chao Hsi-Ming (who is well-known among practitioners in America for his book of simple and potent chi gong longevity exercises), were all from Szech-uan Province. The great Chinese civilization, colorful and exciting with its innumerable esoteric disciplines, was still to be felt as an integral whole into the 70s, although it was rapidly succumbing, via its own decay and Western political-economic pressures, to capitalist industrialization in Taiwan and Communist "up-rooting" on the

Mainland. Until the 70's, it was China experimenting with Western political and economic systems. Now, mainland and island are a cultural hybrid, no longer China.

Chinese medicine and martial arts, which include chi gong, no longer exist in their native context because that context is gone. Out of vital context, nothing survives as it was. Either it mutates to survive, or it is absorbed into something which is, as a whole, quite new. So far, the road has been one of mutation, and its positive or negative direction has yet to be determined. In the American desert the Chinese firecracker became the A-bomb, but in Turkish soil Virginia tobacco became more delicate and sweet.

As the authors here imply, and as I gathered from my limited success in communicating what I had learned in China, without intimate participatory experience in the native context, the true, or natively intended meanings of what one seeks to learn are difficult to apprehend fully or accurately. In addition, because of China's "hy^ brid" state, elements of what was once a balanced whole may be magnified or reduced in relative importanceas was acupuncture in the 1970s, in relation to (then virtually ignored) herbal medicine.

Chi gong in the genuine sense, then, along with the rest of Chinese medicine and martial arts, is a matter out of focus and in a state of mutation. Sensitive to this, the authors have taken great care to make explicit potentially misleading cross-cultural differences and to specify the concept of chi systematically. But this is not only a matter of translation, and here is where the reader comes in.

When we speak of something valuable, we speak, ultimately, of something beyond that metatool of humans, culture. We speak of something intrinsically valuable to human beings themselves, as distinguished, for example, from something valuable to a medical, political, or economic system. Humans everywhere become ill and seek health, and everywhere some humans seek to realize their potentials fully. Human beings from any culture ultimately judge their states of wellness or self-actualization with their senses, and.

because the human senses and the human body are universal, the basic parameters of wellness, self-actualization, and judgement thereof are also universal. Chinese and American patients with the same diagnostics sense that they are better after taking the same herbal medicines, culturally conditioned interpretations notwithstanding. The "transporter-room" that beamed chi gong westward no longer exists, and chi gong is in an unfocused particle state; but the humans at the receiving end may, with care, bring the matter into focus, because the transmission has been from humans to humans.

Common to martial-arts varieties of chi gong is the set of exercises called Yi Jin, which means "using the tendons." It transforms shoulder and forearm tendons into whipcords, capable of great torque. After four years of practicing this discipline about forty-five minutes a day, I was able to visibly flood my arms and hands with blood (for heavier blows) simply by mentally preparing to strike. Then I could immediately deflate my arms by exhaling in a certain way. Only the coordination of breathing with conscious intention could produce these effects. Plainly, the chi can carry messagesinstructions carried out metabolically. Sure enough, according to Chinese medical theory the chi moves the blood and yi (idea or ideational intent) can direct chi. But I did not know that when I began, and my chi gong teacher had not even specified the effects to be achieved. I intuitively realized those potentials, and the effects could be observed by anyone.

The preceding example illustrates the (typically Chinese) notion that, for everything invisible, or metaphysical, there is a visible, or otherwise sense-able correlate. As Dong and Esser remark, chi gong masters tend to be physically impressive. Where there is extraordinary presence of chi, there is also something extraordinary and observable in the gross physical sense, be it the delicacy of an accomplished acupuncturist s manipulations or the impact of a blow.

In the "Special Section on Chi" (chapter 1) I provide, on the basis of ordinary experiences and examples, logical demonstrations of the

existence of chi and explanations of its different kinds. It will become apparent that what is most mystical about chi is Western science's systematic denial of sense evidence of its existence, and of logical implication of its vital primacy. Understanding this, and relying on their senses, American readers need only to remember that "only the balanced receiver can receive the balanced transmission." Esoteric Chinese concepts are all part of a spiritual and physical, or non-sensible and sensible, continuum that is in equilibrium. Americans tend either to be spiritually biased (and so to believe, despite sense data and logic to the contrary) or materially biased, practical, close-minded (and so to disbelieve despite sense data and logic to the contrary). Let us complete the continuum. Ideas can direct chi, but are ideas, then, the end of the continuum? Plainly, thought and imagination are tools, used by another part of ourselves, which has intention. This other part is spirit (jing-shen), that which freely chooses. Spirit produces ideational intent, which directs chi which in turn directs metabolism. Reciprocally, the gross physical body must become a vehicle conducive to any extraordinary chi activity. Through chi gong, "the copper coil becomes platinum," (i.e. conductivity increases), capillary capacity increases, and mass is added.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Chi Gong: The Ancient Chinese Way to Health»

Look at similar books to Chi Gong: The Ancient Chinese Way to Health. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Chi Gong: The Ancient Chinese Way to Health and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.