Te Rrangi Upoko

Guide

Page List

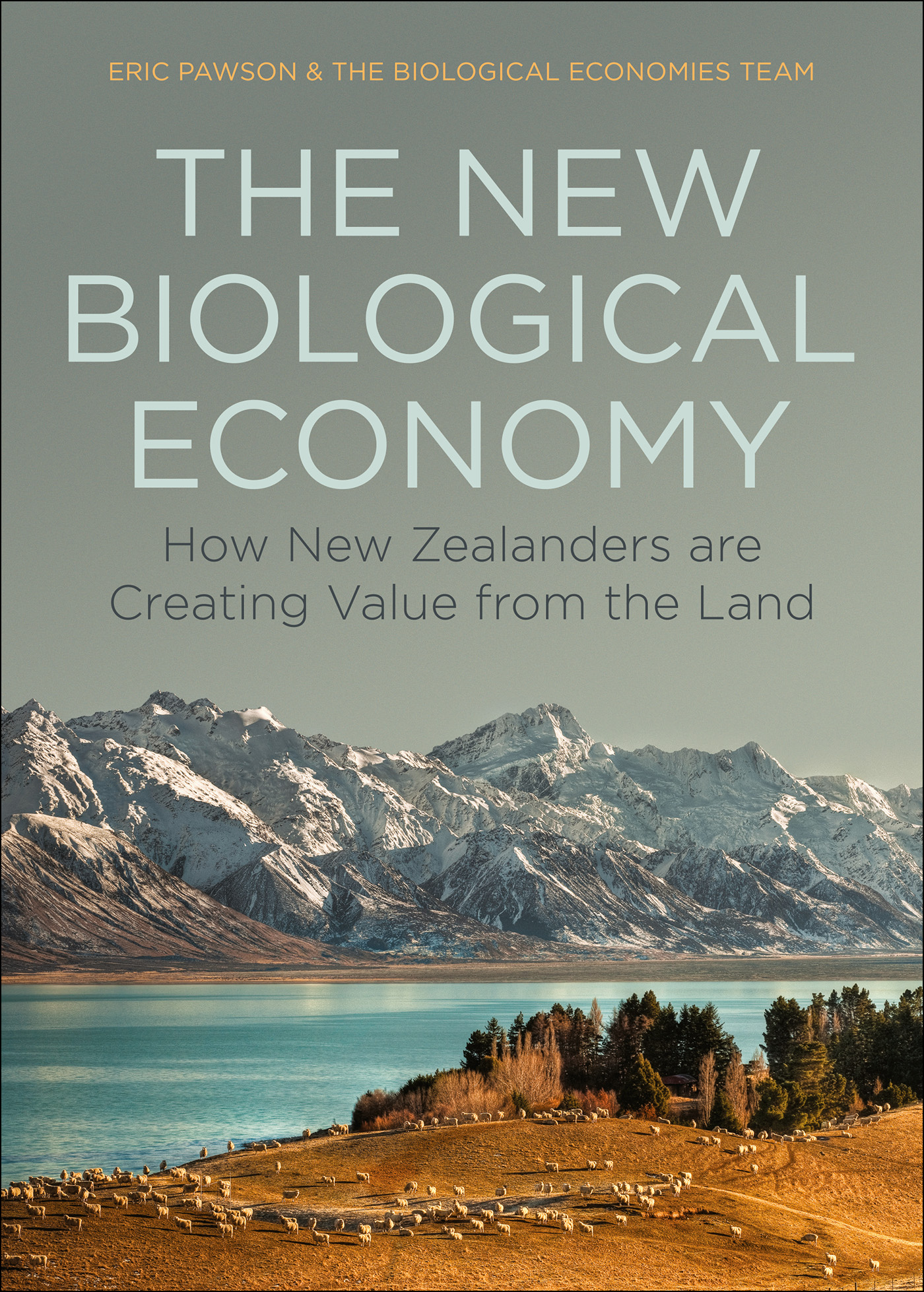

For over a century, New Zealand has built its economy through a series of commodity-based booms from wood and wool to beef and butter. Now the country faces new challenges. By doubling down on dairy farms, arent New Zealanders destroying the clean rivers and natural reputation upon which the countrys primary exports (and tourism) are based? And in a world where value is increasingly rooted in capitaland technology-intensive industries, can New Zealand really sustain its high living standards by growing grass?

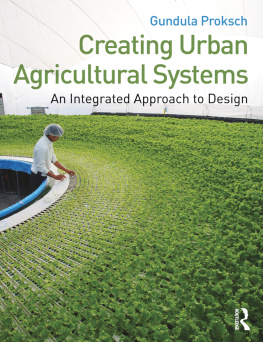

This book takes readers out on to farms, orchards and vineyards, and inside the offices and factories of processors and exporters, to show how New Zealanders are answering these challenges by building The New Biological Economy. From Icebreaker to Mr Apple, from milk and merino to wine and tourism, from highend Berlin restaurants to the shelves of Sainsburys, innovative companies are creating high-value, unique products, rooted in particular places, and making pathways to the niche markets where they can realise that value.

The New Biological Economy poses key questions. Do dairy and tourism have a sustainable future? Can the primary industries keep growing without destroying the natural world? Does the future of New Zealand lie in high tech or in the innovations of a land-based economy?

Eric Pawson is an emeritus professor of geography at the University of Canterbury, recipient of various awards (Distinguished New Zealand Geographer Medal, 2007; National Tertiary Teaching Excellence Award, 2009; University of Canterbury Teaching Medal, 2013), and co-author or co-editor of Making A New Land: Environmental Histories of New Zealand (Otago University Press, 2013), Seeds of Empire: The Environmental Transformation of New Zealand (I.B. Tauris, 2011) and many scholarly articles.

The Biological Economies Team is: Richard Le Heron, Hugh Campbell, Matthew Henry, Erena Le Heron, Katharine Legun, Nick Lewis, Harvey C. Perkins, Michael Roche and Christopher Rosin.

THE NEW BIOLOGICAL ECONOMY

How New Zealanders are Creating Value from the Land

Eric Pawson

and the Biological Economies team

Contents

Preface

Just as this book was being assembled, news broke that the merino outdoor clothing producer Icebreaker, for many people a ground-breaking New Zealand company, had been sold to a US retail giant called VF Corporation, the owner of such well-known brands as The North Face, Timberland and Wrangler. The usual response to moves such as this is to bemoan the fate of yet another successful mid-sized New Zealand enterprise being swallowed up overseas, often because it is not possible to build a global brand from this end of the world. Indeed, that is part of the reason for the Icebreaker sale, as despite reaching into markets in Australasia, western Europe and the western United States, it has been less successful in the rest of the US, Asia and eastern Europe. Although big from a New Zealand perspective, and tremendously innovative with its finely woven merino base layers, it is a tiny company on the global stage, with but a small percentage of merino outdoor-wear sales by value.

But there is another way of reading this story, and that is to focus on how Icebreaker, in little more than twenty years, and in concert with the New Zealand Merino Company, has driven new value for merino. It has done this by developing painstaking relationships with farmers to produce fibre with the right attributes, and creating new uses for fine wool that only a short time ago was not the distinct product that it has since become. Icebreaker has built extensive markets using design and networking, forging these with stories of provenance about New Zealand, its merino sheep and sheep stations to enable customers to understand, trace and value their garments. If the sale of the company to VF underwrites a higher profile and increased sales for the brand, and cements the livelihoods of high country merino producers, and its own design and sales force, then this will be a successful example of building value by scaling across its network of relationships, rather than the common standard by which economic activity is judged, that of scaling up.

The argument of this book is in part that New Zealands biological economy has a long history of attempting to scale up through commodity-based booms that invariably breach environmental limits. The twenty-year-old drive into dairying and the current growth in international tourism are but the latest examples, and each is full of contradictions. The predominant output of the dairy industry is high-volume, low-value milk powder, produced in massive driers in dairy factories. In turn, these sit alongside the pastures on which that milk was produced, many having been brought into production during the dairy boom and irrigated to ensure that the grass will grow using the water that then has to be removed. From the perspective of a values-based and value-driven system, this makes little long-term sense, the more so when low-value commodity markets are often very brittle.

The more important part of the books argument is therefore about with what we are to replace such productivist thinking. It aims to make the case for value creation based on the networks of relationships that the Icebreaker case exemplifies so well. By exploring a number of land-based industries (although the term industry implies a degree of uniformity or sameness that is not appropriate), we try to unravel the characteristics of new ways of creating value. Part of this is that consumers can no longer be treated by producers as if they are invisible or as generic as a 1 kg block of cheese. The ways in which relationships between producer and consumer are being built are explored in a range of cases in the first half of the book: dairying, lamb production, wine, apples, kiwifruit and tourism as well as merino.

We are also interested in the connections between producers and the places in which they work the question of how value can be made to stick, when often much of it is lost up the value chain to locations remote from where it originated. One strategy to tackle this has been provenancing, or telling the stories that relate where something has been made, by whom and how. Provenancing enables consumers to see more directly into the narrative of a product, not only in terms of traceability, but also through the ethical values that it might embody, such as environmental care, the heritage of landscape and animal welfare. In the second part of the book, we discuss a number of places, loosely defined, that are being changed in these ways, or which are driving such changes: enterprise on Mori lands, Banks Peninsula, Central Otago, Hawkes Bay and the New Zealand Food Innovation Network.

Many people have helped us in the making of the book. As explains, we owe the term biological economy to Dr Morgan Williams, a former Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, who suggested it as a way of thinking in terms of the relationships that are vital for the creation of value from biological resources. Our quest to encourage a different way of seeing and understanding value and values, distinct from the long-prevailing science-focused, productivist viewpoint, has generated interest among any number of people in or associated with what are usually called the primary industries. We have also been privileged to further our ideas in Chatham House discussions with food and merino producers, and tourism operatives, as well as officials in Wellington. Each chapter in turn is the outcome of detailed research, and often fieldwork on farms, in orchards, tourist places, shops and factories.