Published by Otago University Press

Level 1, 398 Cumberland Street

Dunedin, New Zealand

www.otago.ac.nz/press

First published 2018

Copyright Peter Hoar

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

ISBN 978-1-98-853119-9 (print)

ISBN 978-1-98-853149-6 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-98-853150-2 (Kindle)

ISBN 978-1-98-853151-9 (ePDF)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand. This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. No reproduction may be made, whether by photocopying or by any other means, unless a licence has been obtained from the publisher.

Editor: Jane Parkin

Indexer: Diane Lowther

Design/layout: Fiona Moffat

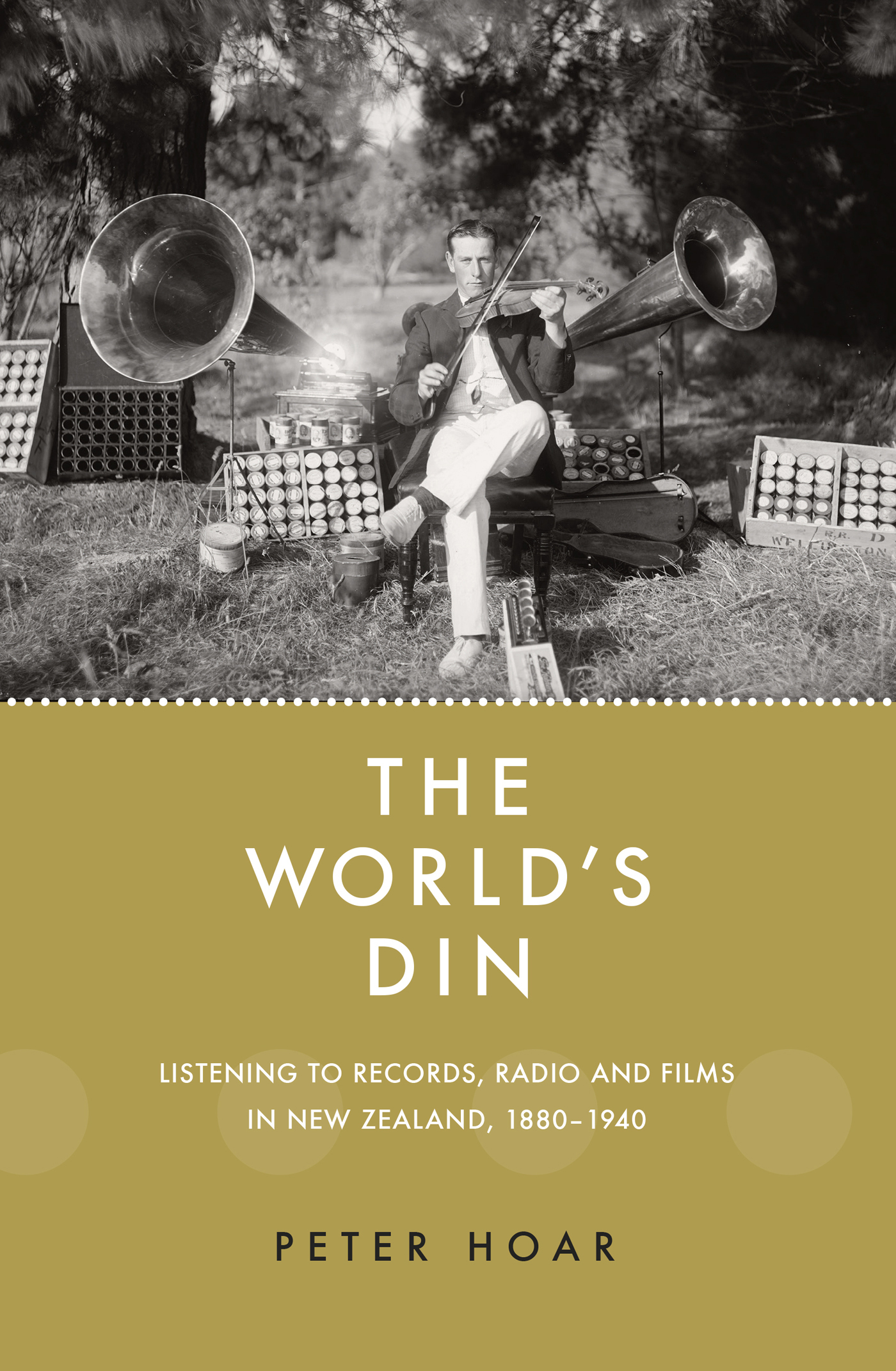

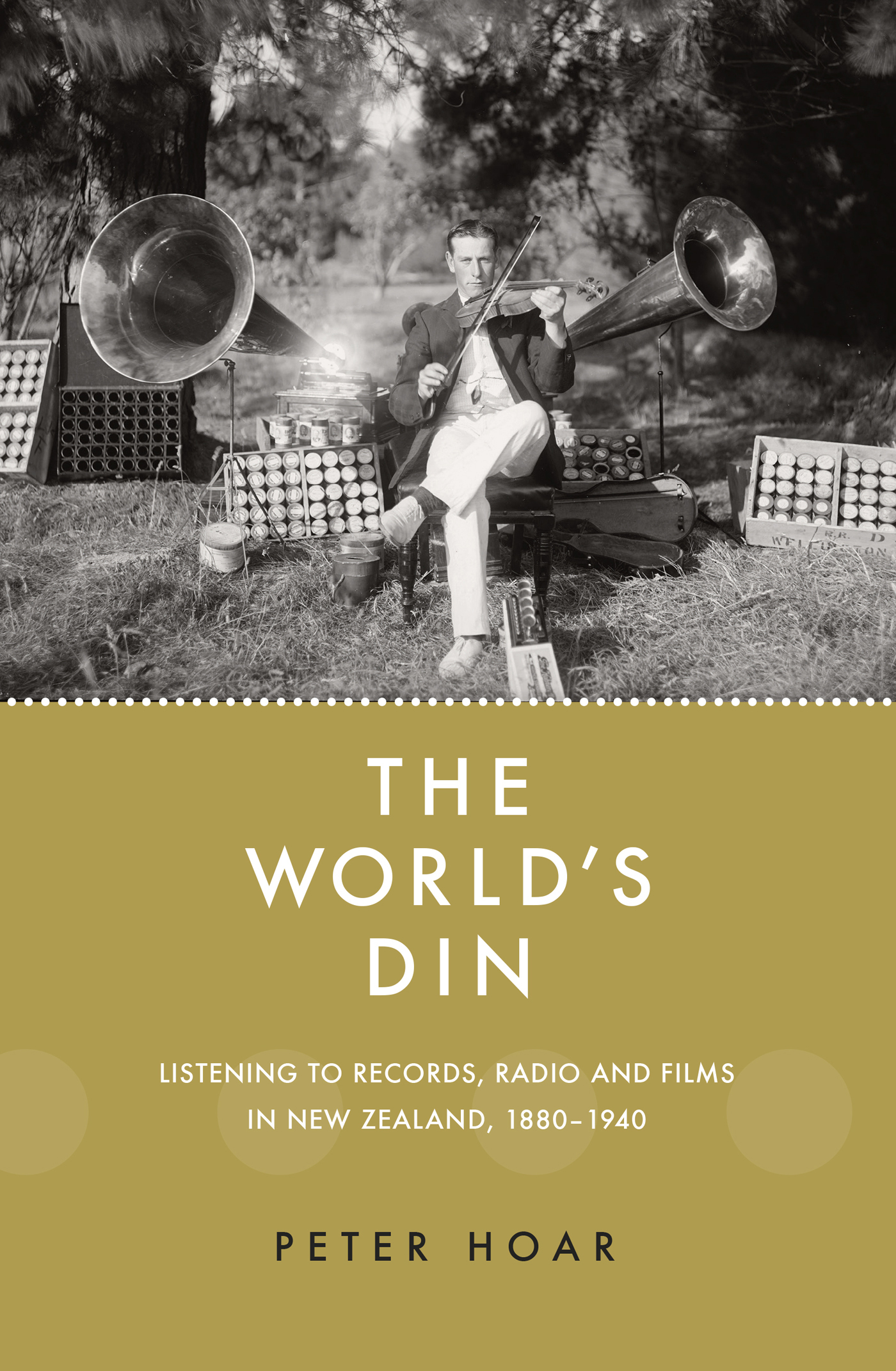

Cover: Violinist with Cylinder Phonograph Collection, Manawatu Heritage, Ian Matheson City Archives, 2015G_Young347_010410

Ebook conversion 2019 by meBooks

CONTENTS

A book is a communal project and I am grateful to all the people who have helped me along the way.

This book began life as PhD thesis, so first thanks go to my supervisors Associate Professor Caroline Daley and Dr Joseph Zizek along with the rest of the staff at the University of Aucklands History Department.

Many thanks also to all my colleagues at Auckland University of Technology for their support, encouragement and comradeship.

Research would be impossible without dedicated and committed librarians and archivists. Much gratitude and plaudits to all the individuals and institutions that collect, organise, index, catalogue, preserve and generally maintain the raw materials of our histories.

Im very grateful to Otago University Press for taking this project on board. Thanks to Rachel Scott, Imogen Coxhead and Fiona Moffat for their patience, guidance and efforts. A very big thanks to editor Jane Parkin for her peerless work on the text. I had a very good team to work with but of course, any mistakes are all mine.

A really, really big thank you in upper case, 30-point font and with fireworks too to my friends and family for all their support, kindness, laughs and love. Finally, my heartfelt thanks to Robyn, for being there with me.

T Its just the way things go, Roger said. Changes in audio technologies had, it seemed, spelled the end for one of Aucklands most loved musical institutions.

Happily, it was not the case. Marbecks reopened in Queens Arcade in 2014 and is still going strong.

At the heart of these assertions are differing concepts about the nature of listening and how it is shaped by social, cultural and personal factors. Frequency ranges and other qualities of audio technologies can be measured and charted, but it is quite another thing to objectively quantify concepts like warmth. Listening to audio machines is not a science, and the vinyl revival shows just how culturally loaded and nuanced our ways of hearing the world can be.

Since 1877 recorded sound has been stored on tinfoil, wax cylinders, shellac discs, magnetic tape, vinyl records and CDs. These are all tangible artefacts. They take up space, and can be handed around, scratched, drawn on, smashed or carefully preserved as vessels of personal memory. They are also objects that fundamentally altered human experience by disembodying sounds from the people who made them. Digital technology takes this disembodiment even further by turning sounds into combinations of ones and zeros that form the binary code of software. Recorded sound is now weightless and massless, and can be instantaneously moved around the world via the internet. The world is there for the hearing by anyone who has a computer or a phone.

The digital moment might seem to be a revolution in the ways we listen. We have no more need for objects such as records or CDs; audio files can be stored in the cloud or on an iPod. Radio stations now have to compete with services like Spotify, iTunes or Pandora that allow listeners to hear continuous music of their choice with or without advertisements (in that typically modern twist, we now pay extra to be spared the overt assault of commercialism). Films can be experienced on large screens at home with high-quality sound systems, or on laptops or tablets wherever the viewer happens to be. But these digital technologies are extensions of the audio machines that have gone before and in vinyls case have come back again. The real shock of the sonic new happened between 1877 and the late 1930s.

The experiences of sound through the technologies discussed in this book were part of the disruptive experience of modernity. Film scholar James Lastra describes it as an experience of profound temporal and spatial displacements, of often accelerated and diversified shocks, of new modes of society and of experience that has been shaped by media technologies. Gramophones, radios and films appear to fragment perceptions of time and space through sound. Sounds are separated from their sources through recordings and transmission. This has added a new dimension to human experience. Before the development of machines such as the phonograph, sounds had been heard only in the vicinity of the sounder.

The iPod is related to the portable gramophone in terms of listening practices: both are used by listeners in creative ways to experience the spaces and sounds of modernity. The iPod is not a revolution in itself; it is a refinement of the technology that captured, stored and replayed sounds which was developed by Thomas Edison and others during the later decades of the nineteenth century. Modern radio and cinema practices, too, may seem completely different from their historical antecedents, but they are also refinements of earlier technological developments.

These strange, disorientating, sometimes disturbing and exciting effects were heard and felt in New Zealand as they were worldwide.

The sounds of history in New Zealand have received very little attention from historians and other scholars. Discussions of recording, radio and cinema tended to focus on the fortunes of institutions and individuals rather than how these technologies sounded. There has also been a nationalistic focus on making sounds in New Zealand, rather than on New Zealanders hearing the sounds of the world. The notion of hearing the world is in tune with the challenge offered by New Zealand historian Peter Gibbons, who suggested that New Zealands historians needed to move beyond narrow ideas of national identity and pay more attention to the worlds place in New Zealand. These experiences include listening.

The idea of hearing the world connects the rich acoustic tapestry of everyday life with the global patterns of industrial production and consumption of canned sounds. Understanding how popular culture was heard in New Zealand is a way of recovering some of the richness and variety of past everyday life. Gibbons idea is particularly relevant for this book given that the great majority of the recorded sounds heard here have been from other places, mainly the United States. Concentrating on films or records made in this country ignores most of the sonic cultures historically experienced and enjoyed by New Zealanders.

Next page