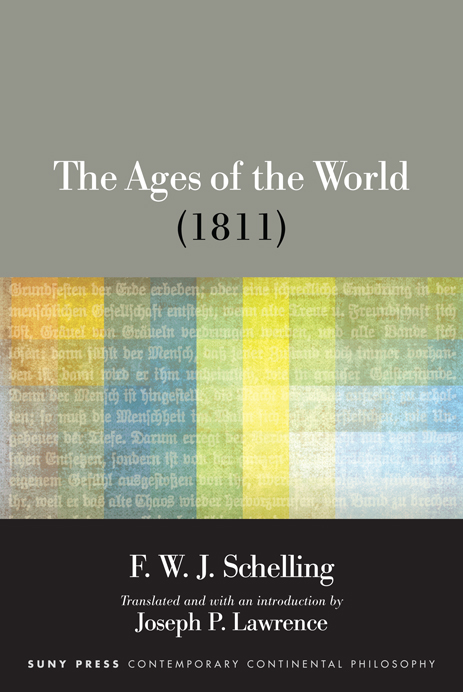

The Ages of the World

(1811)

SUNY series in Contemporary Continental Philosophy

Dennis J. Schmidt, editor

The Ages of the World

Book One: The Past

(Original Version, 1811)

Plus Supplementary Fragments,

Including a Fragment from Book Two (the Present)

along with a Fleeting Glimpse into the Future

F. W. J. Schelling

Translated and with an Introduction by

Joseph P. Lawrence

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2019 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Schelling, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von, 17751854, author. | Lawrence, Joseph P., 1952 translator, writer of introduction.

Title: The ages of the world : Book one : the past (original version, 1811) plus supplementary fragments (18111813), including a fragment from Book two (the present) along with a fleeting glimpse into the future / F. W. J. Schelling ; translated and with an introduction by Joseph P. Lawrence.

Other titles: Weltalter. English

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2019] | Series: SUNY series in contemporary continental philosophy | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018027704 | ISBN 9781438474052 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438474076 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Ontology.

Classification: LCC B2894.W42 E5 2019 | DDC 193dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018027704

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Bertel Thorvaldsen, Monument for Auguste Bhmer, 1814

(based on a design of F. W. J. Schelling dated April 25, 1811)

Contents

Translators Introduction

The Ecstasy of Freedom

And I know what you will say now: That if truth is one thing to me and another thing to you, how will we choose which is truth? You dont need to choose. The heart already knows. He didnt have His Book written to be read by what must elect and choose, but by the heart, not by the wise of the earth because they dont need it or maybe the wise no longer have any heart, but by the doomed and lowly of the earth who have nothing else to read with but the heart.

William Faulkner, Go Down Moses

I.

In the twelfth chapter of Book XI of the Confessions , Saint Augustine famously referred to a jester who, when asked, What was God doing before he made heaven and earth? replied facetiously, he was preparing hell for those who dare to ask such questions. Given that The Ages of the World ( Die Weltalter ) did dare to ask the question, one might consider the morass into which Schelling subsequently sank, in which he spent many years writing and rewriting a text that he never deemed publishable, as evidence that the jester was wiser than Augustine realized. There are certain questions, we are told often enough, that philosophy is not supposed to explore. Believing positivists and atheists say this just as decisively as do believing Christiansand for many of the same reasons. One wants to know, after all, what one thinks one knows, so much so that even philosophers find themselves unsettled by questioning that is truly radical. The fact that the Weltalter ended in failure might suggest

This, the image of a not-yet God himself undergoing hell, represents the only possible solution to the problem of why God would allow so much suffering in the world. To the degree that we are where God was , the affirmation of our need to suffer is a function of Gods own self-affirmation. The idea is coherent and, well understood, grants genuine solace (why would one ever want to pray to a god so perfect as to be incapable of empathy?). Even so, applied to the Father, it has consistently been rejected as hereticaldespite the fact that the purported Son of God (and no one can know the Father except through the Son) was himself horrifically crucified, abandoned in his time of greatest need, and cast into hell. If Christianity has had to declare the very heart of Christianity heretical, it is presumably because its truth is too heavy to bear. Schellings great accomplishment is that, in an effort to philosophically ground a Christianity that would finally be Christian, he actually took the burden of such truth on himself.

its truth is to lighten its burden through the generation of sound and meaning out of an interior so full that it can no longer remain in itself (WA 57).

what we still celebrate as the act of creation. Philosophically construed, what Schelling was looking for was a compelling alternative to the mechanical conception of time as something stretched out into infinity, with neither beginning nor end. His purpose in illuminating the abyss of the past was to uncover the origin of time itself. In the same way, his projected goal for a third book on the absolute future, one that he never even started to write, was to reveal the end of all things: time so fully articulated that it would serve as a mirror for the lucid purity of eternity. Caught between these poles is, of course, the world we now experience, the subject of what was to have been his second book, The Present .

By 1815 Schelling succeeded in working out a compressed version of the organism of time in the form of the theory of potencies that Eric Voegelin referred to as perhaps the profoundest piece of philosophical thought ever elaborated. It is a judgment with which as a Schelling scholar I am happy enough to concur, though I would like to add to it a simple observation: profundity of thought may indeed take a theoretical form, but theory itself must be grounded in intuition. To think deeply requires a prior descent into the depths. This is why many have considered the 1811 version of the Weltalter to be more compelling than its later revisions. It is a text filled with such a depth of inexpressible meaning that it literally rewrote itself twenty times or more.

If I have kept my eye fixed on what came first, most commentators have stayed focused on the failure of the project as a whole, searching for whatever mistake in thinking might have generated the pile of rejected manuscripts Fuhrmans found buried away in the archives. The failure is hard to deny. Schelling, the philosopher who as a young man published a significant work each and every year, was now, at the age of thirty-six, suddenly unable to publish. This is the remarkable fact that captures the imagination. From 1810, when he began writing, until 1833, when he completed his last Munich lecture on Das System der Weltalter , as its guiding ideal, often posturing as if the right balance of technology and enlightened political institutions will one day constitute the community of nations and thereby secure the happiness of humanity.

But, as poets know so well, the eschaton of the future lives only in such imaginings, for it is precisely not a program to be achieved by political action and technological innovation. In itself, the absolute future, like the absolute past, is hidden away in eternity. Thus those stunning words that can be found in one of the fragments translated in this volume, words that Schelling later chose as the opening to the 1815 version of the Weltalter : God in his wisdom ( frsichtig ) hides in dark night not only the end of time to come but the beginning of time past (WA 198 and 220). The wisdom of God is the knowledge that time, as fixed as it is in the form of a simple progression from past to present to future, is always held open by the concealment in eternity of its absolute beginning and end. As resolutely as Schelling attempted to pry open the past, it always closed itself back again, in keeping with that infernal logic by which Napoleon abolished is yet the Hitler to come.