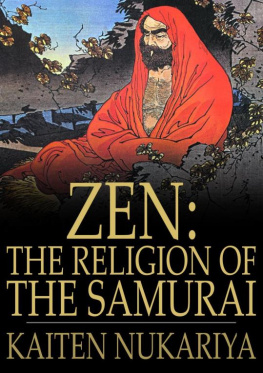

Kaiten Nukariya - The Religion of the Samurai: A Study of Zen Philosophy and Discipline in China and Japan

Here you can read online Kaiten Nukariya - The Religion of the Samurai: A Study of Zen Philosophy and Discipline in China and Japan full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 0, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Religion of the Samurai: A Study of Zen Philosophy and Discipline in China and Japan

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:0

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Religion of the Samurai: A Study of Zen Philosophy and Discipline in China and Japan: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Religion of the Samurai: A Study of Zen Philosophy and Discipline in China and Japan" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Kaiten Nukariya: author's other books

Who wrote The Religion of the Samurai: A Study of Zen Philosophy and Discipline in China and Japan? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Religion of the Samurai: A Study of Zen Philosophy and Discipline in China and Japan — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Religion of the Samurai: A Study of Zen Philosophy and Discipline in China and Japan" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To-day Zen as a living faith can be found in its pure form only amongthe Japanese Buddhists. You cannot find it in the so-called Gospelof Buddha anymore than you can find Unitarianism in the Pentateuch,nor can you find it in China and India any more than you can findlife in fossils of bygone ages. It is beyond all doubt that it canbe traced back to Shakya Muni himself, nay, even to pre-Buddhistictimes, because Brahmanic teachers practised Dhyana, orMeditation, from earliest times.

But Brahmanic Zen was carefully distinguished even by earlyBuddhists as the heterodox Zen from that taught by the Buddha. Our Zen originated in the Enlightenment of Shakya Muni, which tookplace in his thirtieth year, when he was sitting absorbed in profoundmeditation under the Bodhi Tree.

It is said that then he awoke to the perfect truth and declared: "Allanimated and inanimate beings are Enlightened at the same time."According to the tradition

An epoch-making event took place in the Buddhist history of China byBodhidharma's coming over from Southern India to that country inabout A.D. 520. It was the introduction, not of the deadscriptures, as was repeatedly done before him, but of a living faith,not of any theoretical doctrine, but of practical Enlightenment, notof the relies of Buddha, but of the Spirit of Shakya Muni; so thatBodhidharma's position as a representative of Zen was unique. Hewas, however, not a missionary to be favourably received by thepublic. He seems to have behaved in a way quite opposite to that inwhich a modern pastor treats his flock. We imagine him to have beena religious teacher entirely different in every point from a popularChristian missionary of our age. The latter would smile or try tosmile at every face he happens to see and would talk sociably; whilethe former would not smile at any face, but would stare at it withthe large glaring eyes that penetrated to the innermost soul. Thelatter would keep himself scrupulously clean, shaving, combing,brushing, polishing, oiling, perfuming, while the former would beentirely indifferent to his apparel, being always clad in a fadedyellow robe. The latter would compose his sermon with a great care,making use of rhetorical art, and speak with force and elegance;while the former would sit as absolutely silent as the bear, and kickone off, if one should approach him with idle questions.

No sooner had Bodhidharma landed at Kwang Cheu in Southern China thanhe was invited by the Emperor Wu, who was an enthusiasticBuddhist and good scholar, to proceed to his capital of Chin Liang.When he was received in audience, His Majesty asked him: "We havebuilt temples, copied holy scriptures, ordered monks and nuns to beconverted. Is there any merit, Reverend Sir, in our conduct?" Theroyal host, in all probability, expected a smooth, flattering answerfrom the lips of his new guest, extolling his virtues, and promisinghim heavenly rewards, but the Blue-eyed Brahmin bluntly answered: "Nomerit at all."This unexpected reply must have put the Emperor to shame and doubt inno small degree, who was informed simply of the doctrines of theorthodox Buddhist sects. 'Why not,' he might have thought withinhimself, 'why all this is futile? By what authority does he declareall this meritless? What holy text can be quoted to justify hisassertion? What is his view in reference to the different doctrinestaught by Shakya Muni? What does he hold as the first principle ofBuddhism?' Thus thinking, he inquired: "What is the holy truth, orthe first principle?" The answer was no less astonishing: "Thatprinciple transcends all. There is nothing holy."

The crowned creature was completely at a loss to see what the teachermeant. Perhaps he might have thought: 'Why is nothing holy? Arethere not holy men, Holy Truths, Holy Paths stated in the scriptures? Is he himself not one of the holy men?' "Then who is that confrontsus?" asked the monarch again. "I know not, your majesty," was thelaconic reply of Bodhidharma, who now saw that his new faith wasbeyond the understanding of the Emperor.

The elephant can hardly keep company with rabbits. The pettyorthodoxy can by no means keep pace with the elephantine stride ofZen. No wonder that Bodhidharma left not only the palace of theEmperor Wu, but also the State of Liang, and went to the State ofNorthern Wei. but without success.

China was not, however, an uncultivated land for the seed ofZennay, there had been many practisers of Zen before Bodhidharma.

All that he had to do was to wait for an earnest seeker after thespirit of Shakya Muni. Therefore he waited, and waited not in vain,for at last there came a learned Confucianist, Shang Kwang (Shin-ko)by name, for the purpose of finding the final solution of a problemwhich troubled him so much that he had become dissatisfied withConfucianism, as it had no proper diet for his now spiritual hunger.Thus Shang Kwang was far from being one of those half-heartedvisitors who knocked the door of Bodhidharma only for the sake ofcuriosity. But the silent master was cautious enough to try thesincerity of a new visitor before admitting him to the MeditationHall. According to a biography of his, Shang Kwang was notallowed to enter the temple, and had to stand in the courtyardcovered deep with snow. His firm resolution and earnest desire,however, kept him standing continually on one spot for seven days andnights with beads of the frozen drops of tears on his breast. Atlast he cut off his left arm with a sharp knife, and presented itbefore the inflexible teacher to show his resolution to follow themaster even at the risk of his life. Thereupon Bodhidharma admittedhim into the order as a disciple fully qualified to be instructed inthe highest doctrine of Mahayanism.

Our master's method of instruction was entirely different from thatof ordinary instructors of learning. He would not explain anyproblem to the learner, but simply help him to get enlightened byputting him an abrupt but telling question. Shang Kwang, forinstance, said to Bodhidharma, perhaps with a sigh: "I have no peaceof mind. Might I ask you, sir, to pacify my mind?" "Bring out yourmind (that troubles you so much)," replied the master, "here beforeme! I shall pacify it." "It is impossible for me," said thedisciple, after a little consideration, "to seek out my mind (thattroubles me so much)." "Then," exclaimed Bodhidharma, "I havepacified your mind." Hereon Shang Kwang was instantly Enlightened.This event is worthy of our notice, because such a mode ofinstruction was adopted by all Zen teachers after the firstpatriarch, and it became one of the characteristics of Zen.

Bodhidharma's labour of nine years in China resulted in theinitiation of a number of disciples, whom some time before his deathhe addressed as follows: "Now the time (of my departure from thisworld) is at hand. Say, one and all, how do you understand the Law?" Tao Fu (Do-fuku) said in response to this: "The Law does not lie inthe letters (of the Scriptures), according to my view, nor is itseparated from them, but it works." The Master said: "Then you haveobtained my skin." Next Tsung Chi (So-ji), a nun, replied: "AsAnanda which he hadbrought from India to Hwui Ko, as a symbol of the transmission of theLaw, and created him the Second Patriarch.

After the death of the First Patriarch, in A.D. 528, Hwui Ko did hisbest to propagate the new faith over sixty years. On one occasion aman suffering from some chronic disease called on him, and requestedhim in earnest: "Pray, Reverend Sir, be my confessor and grant meabsolution, for I suffer long from an incurable disease." "Bring outyour sin (if there be such a thing as sin)," replied the SecondPatriarch, "here before me. I shall grant you absolution." "It isimpossible," said the man after a short consideration, "to seek outmy sin." "Then," exclaimed the master, "I have absolved you.Henceforth live up to Buddha, Dharma, and Samgha."Ming (Sin zin-mei, On Faith and Mind), a metrical exposition of thefaith.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Religion of the Samurai: A Study of Zen Philosophy and Discipline in China and Japan»

Look at similar books to The Religion of the Samurai: A Study of Zen Philosophy and Discipline in China and Japan. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Religion of the Samurai: A Study of Zen Philosophy and Discipline in China and Japan and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.