This book made available by the Internet Archive.

A Fresh Note to Introduce this Edition

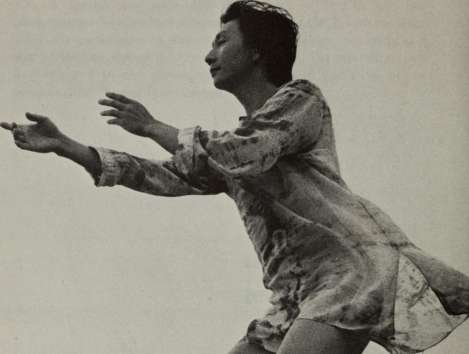

The t'ai chi I practice and talk about is ever-constant, and ever-changing. From time to time, an ex-pupil appears in my workshop and exclaims: "But, you have changed this..." My answer is "Yes, I have. I move on and beyond...but you got stuck back then and there." My variations of teaching continue to develop and transform, but the essence is the same. Tao is still mysterious and ineffable. It continues to reveal itself to us in many ways: in the hidden fragrance of a lone orchid in deep mountain, in windflow and watercourse ways, and in the simplest effortlessness of fish in water and bird in flight. Above all, it is in all of us when we become active participants in living, instead of being merely observers of life. It is alive, living in all of us, in our daily doing and being.

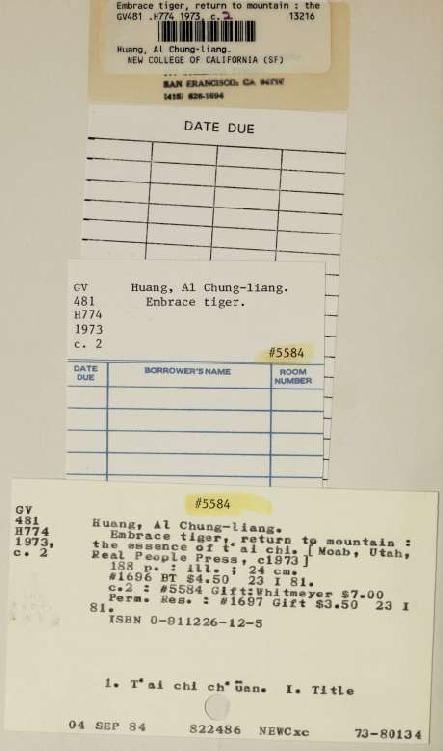

Tao is change, many changes, as life continues to expand and eliminate, evolve and resolve in its many dimensions. Our dear friend Alan Watts passed on shortly after he wrote the forward to this book. The spirit of our East-West synthesis lives on...With the loving support of the Society of Comparative Philosophy, I created, in Alan's memory, Lan T'ing Institute. Lan T'ing has offered summer and winter residential seminars since 1975 and has become the living Tao Foundation, a crystallization of our t'ai chi family network with an international membership. In addition to the long-term programs which have taken us to Hawaii and Mexicowith prospects

of Europe and the Far East, and special cultural exchange trips to Chinawe are creating a variety of lectures, concerts and service programs with amazingly inexhaustible energy and loving. Some of my recent "Living Tao" collaborations have been blessed by Jazz flautist Paul Horn, Buddhist and Taoist scholar John Blofeld, Lama Anagarika Govinda, poet-filmmaker James Broughton, potter-sculptor Daniel Rhodes, composer Pauline Oliveros and mythologist Joseph Campbell.

Being a part of Laura Huxley's "Our Ultimate Investment" project, I became more and more involved in the work/play with children, family and the new life-force with senior citizens. My mother Lee Chih-chang has been another inspiration. At age 68, recently quitting some 50 years of heavy smoking, she practices t'ai chi, kung-fu, and plays golf daily. She walked off with the show both years at the Festival of the Happy Martial Arts as a special guest performer, with her gut-grunting, fist-punching, leg-kicking, a la Bruce Lee Martial art, Pa Chi Ch'uan, based on the 64 / Ching hexagrams. She visits my seminars and shares teaching with me frequently, and loves being "Mama Huang" to all my t'ai chi friends. She is particularly regal and flowing when she swings and boogies with us, "digging" the current disco beats!

In my family life, my wife and I continue to play the yin-yang game with new clarity, flow, and frustrations. She has taught me how to garden as a t'ai chi practice, to put my love for nature into flowers, vegetation and the "dirt in my fingernails" earth. Each day we learn more ways to enjoy simple day-to-day household events, being together as a couple and separate as individuals. Tysan, our second daughter, at 4 years is the new t'ai chi master of the Huang family: she still has the quintessance. Largolee (Lark), the little buddha sitting transfixed at dawn in Barry Steven's Utah cave in the Afterword of this book, is a tall and willowy 3rd grader who "hates" all the macho boys, and thinks the "gender" games are really dumb!

These days some of my t'ai chi disciplines are climbing trees, rolling in the waves, and flying kites with the children. Juggling three LaCrosse balls while gliding on Lark's skateboard is still a big

challenge to me. But Tysan always applauds encouragingly each time I fall...

Happy reading in your moving,

Al Chung-liang Huang

late Spring and early summer

in the Middle-west 1978

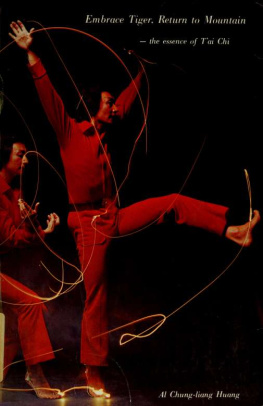

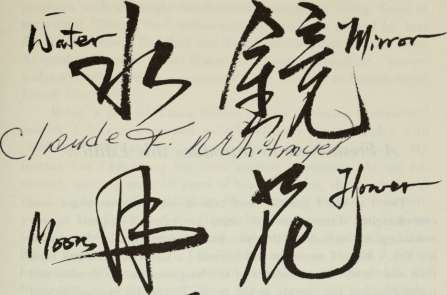

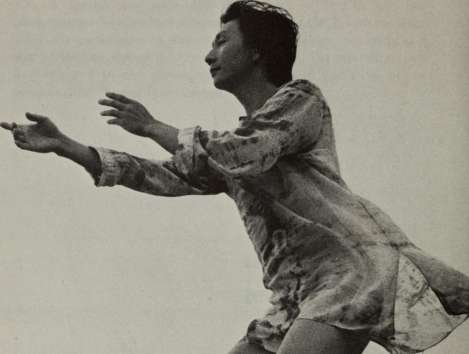

P.S. A special love note and thank you to Si Chi Ko, our photographer-friend who has been sharing the DANCE with me since 1967. He participates in almost all of my seminars, recording as a way of his Tao, the spirit of our t'ai chi learning. For this edition, we have selected 16 new photographs to share with you some of our visions of the "Living Tao" essence.

<) *

Foreword

My association with the author of this book is not simply that I have read his work and like it. We have known each other for quite a number of years. We have jointly conducted seminars at Esalen Institute and similar places, where I have spoken of Taoist philosophy and he has demonstrated its practice in terms of t'ai chi movement. We have spent much time together exploring this venerable philosophy, both intellectually and practically, and have come to a consensus of understanding and feeling about it such that I can say of the relationship between us that East and West have undoubtedly met and, for me, this is no small matter.

To begin with, Huang teaches in a way that is unusual for an Asian master and, when I think back over my own schooling, for Western masters as well. He begins from the center and not from the fringe. He imparts an understanding of the basic principles of the art before going on to the meticulous details, and he refuses to break down the t'ai chi movements into a one-two-three drill so as to make the student into a robot. The traditional way (whether in t'ai chi. zen, or yoga) is to teach by rote, and to give the impression that long periods of boredom are the most essential part of training. In that way a student may go on for years and years without ever getting the feel of what he is doing. This is as true of theology, law. medicine, and mathematics as it is of t'ai chi, so that we have many "masters" of these disciplines who are plainly incompetent, no more than

well-contrived imitations of the real thing. The strengths and weaknesses of human nature are the same in Asia as in the West: there are plenty of Buddhist, Hindu, and Taoist equivalents of pompous bishops, knife-happy surgeons, and pedantic scholars who cannot see the forest for the trees.

T'ai chi exemplifies the most subtle principle of Taoism, known as wu-wei. Literally, this may be translated as "not doing," but its proper meaning is to act without forcingto move in accordance with the flow of nature's course which is signified by the word Tao, and is best understood from watching the dynamics of water. Wu-wei is exemplified in the art of sailing, in which one uses intelligence, as distinct from rowing, in which force of muscle is dominant. In such arts as sailing, gliding, surfing, and skiing there must be no turns through sharp angles, for in such sharp turns human muscle would have to defy the environment of water, wind, or gravity instead of using it.

Next page