Preface

When in the mid-1980s I was studying Muslims prominent in the subcontinents recent history for my Understanding the Muslim Mind, an obvious subject was the towering figure of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan. I had first met him in 1945 or 1946, when I was a boy of about ten and he was visiting Delhi and staying, along with his older brother Dr Khan Sahib, in my fathers Connaught Circus flat. The events of August 1947 soon made him an outsider, but I was able to meet him again, during his visits to India, in 1969 and 1987. However, as far as Understanding the Muslim Mind was concerned, I was not taking up any living person, which in the mid- 1980s Badshah Khan very much was, despite being in the mid-nineties himself.

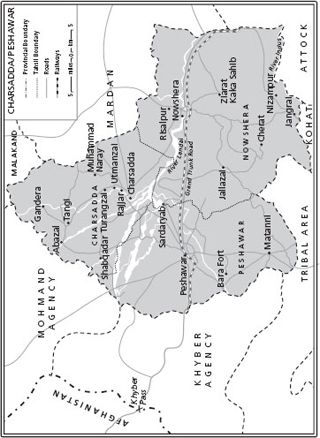

Now, after all these years, I feel thankful to be able to offer this portrait. A goad towards it was applied to me on 9 September 2001 when my wife and I were visiting Badshah Khans family in the countryside of the Peshawar/Charsadda valley. Asfandyar Khan, eldest son of Badshah Khans second son Wali Khan and a political player himself in the Frontier and in Pakistan as a whole, said that he missed a biography of his grandfather that the subcontinents newer generations would want.

In that conversation with Asfandyar Khan, which took place while Afghanistan was yet under Taliban control, we also discussed Indo-Pak relations, Kashmir and Musharraf, and religious extremism and terrorism as well. Two nights later, on the morning of 11 September, my wife and I flew back to Delhi. That evening, on TV, we saw the crumbling of New Yorks Twin Towers.

In the new phase ushered in by that event, Badshah Khans life, it was obvious, had taken on additional meaning. I knew I had to write the biography.

Here it is, with all its imperfections. Whether it will fully satisfy Asfandyar Khan I do not know. I have written it for the subcontinents newer generations, but also for the many everywhere who are being pressurized to believe in an unbridgeable gulf between Muslims and the rest.

Among those to whom I am indebted for this book are several descendants of Badshah Khan and of his older brother, Dr Khan Sahib, including Wali Khan and Mehr Taj, son and daughter of Badshah Khan. I will not name all the others, but I must refer to the wonderful hospitality and help, when in May 2003 I again visited the Charsadda valley and Islamabad, of Anwar Khan, grandson of Dr Khan Sahib, his wife Rashida, and their children. Several others interviewed by me and named in the text also provided valuable facts and insights. My sincere thanks to them.

I am grateful, too, to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, which hired me as a visiting professor from the Fall of 2002 but allowed me to squeeze time out to research and write this study.

Finally, I offer thanks to two persons at Penguin, Kamini Mahadevan, who commissioned this study, and Malini Sood, who has edited it with patience and skill.

Rajmohan Gandhi

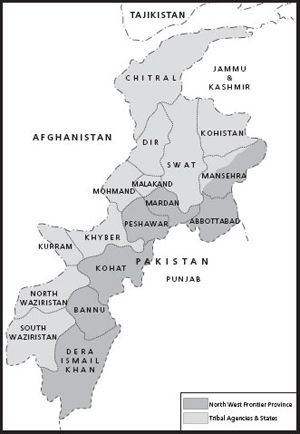

The Setting

Fifty years ago or thereabouts, Badshah Khan of the Peshawar valley was, for most people of the subcontinent and for the British who had recently vacated it, the Pathan, or, to use preferred contemporary (and rather more accurate) expressions, the Pakhtun or Pashtun.

In the 1940s and the 1950stimes that surrounded freedoms pain-filled glorythe word Pathan never failed to conjure up the image of this man coming from a region that classical India knew as Gandhara, an immensely tall figure with an absolutely straight back, a great nose, kindly eyes, and a permanent aura of nonviolent defiance. Exercising an undeniable right, a subsequent generation in Pakistan, India, and elsewhere chose, however, to forget him.

This process was aided by turbulence in Afghanistan, which always affects the Pathans of the Frontier. In the 1970s the Afghans, regarded by Badshah Khan as his kin, turned, as they had often done in their history, to infighting and a coup. Then began an absorbing sequence of occupation by the Soviet Union, resistance to that occupation, liberation, civil wars, and Taliban rule. It was not easy, during this long phase, to retain a focus on Badshah Khans life. Even though he had lived until 1988, by when the end of Soviet occupation was a matter only of time, his leadership of the Pathans struggle against the British and his post-1947 striving for Pakhtun dignity seemed distant achievements, unconnected with what was happening in Afghanistan and, as a result, in the NWFP, which harboured thousands of Afghan mujahedin and hundreds of thousands of Afghan refugees.

But 9/11 recalled Badshah Khan to the public mind, and not on the subcontinent alone. The New York Times wrote (on 7 December 2001, in an Op-Ed piece by Karl E. Meyer) about The Peacemaker of the Pashtun Past, who not so long ago symbolized peace and tolerance and seemed an antithesis of a later Pashtun, Mullah Omar of Kandahar (a place frequently but erroneously confused with Gandhara), the fanatical Taliban leader, foe of the USA, and Osama bin Ladens host in Afghanistan.

Yet Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khanaka Badshah Khan, Bacha Khan, Baba, Khan Sahib, and the Frontier Gandhilived for more than peace and tolerance; he lived also for justice. Which is how he became a political prisoner for about twelve years under the British, and for an additional fifteen years after the founding of Pakistan, into which his Peshawar valley and the rest of the North-West Frontier Province had been merged. However, the contrast with Mullah Omar is dramatic enough, from a variety of angles.

One, the struggle for which Badshah Khan mobilized his fellow Pathans was nonviolent.

Two, in him a passion to find an answer to the code of revenge to which Pathans appeared to be sworn seemed to equal a passion for independence from foreign rule. To this Muslim, forgiveness was part of Islam.

Three, non-Muslims seemed as important as Muslims to Badshah Khan, who said that he and his Pathans would protect the Hindus, Sikhs and Christians living in the overwhelmingly Muslim North-West Frontier Province. One man who had touched his life was a white Christian schoolmaster called Wigram; another was a Hindu called Mohandas Gandhi.

Four, Badshah Khan wanted Pashtun women to study, work and lead; in 1932 he sent his daughter Mehr Taj, who had just entered her teens, to study in England.