The Complete Works of

JULIAN

(AD 331/332-363)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2017

Version 1

The Complete Works of

JULIAN THE APOSTATE

By Delphi Classics, 2017

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Julian

First published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2017.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 9781786563910

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

The Translations

Hagia Sophia, Constantinople, modern-day Istanbul Flavius Claudius Julianus, Julian the Apostate, was born in 332 in Constantinople.

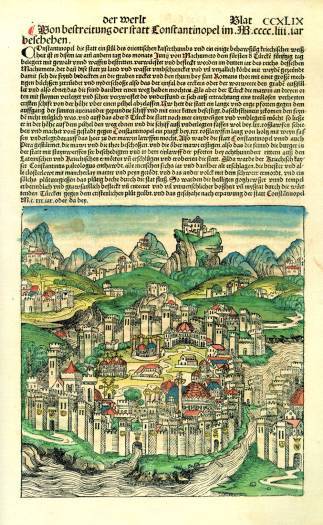

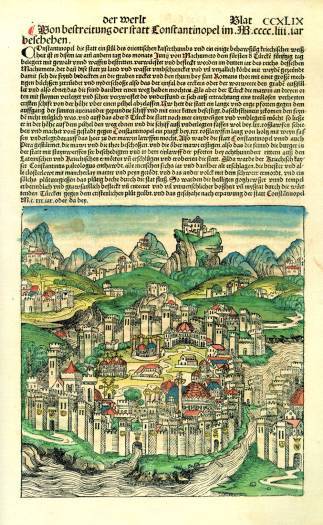

Page depicting Constantinople in the Nuremberg Chronicle published in 1493, forty years after the citys fall to the Muslims

Istanbul today

ORATIONS

Translated by Wilmer C. Wright

CONTENTS

Marble head representing Emperor Constantine the Great, Capitoline Museums, Rome. Julian was the half brother of Emperor Constantine I.

Julian solidus, c. 361. The obverse shows a bearded Julian with an inscription, father of the nation. The reverse depicts an armed Roman soldier bearing a military standard in one hand and subduing a captive with the other, a reference to the military strength of the Roman Empire, and spells out VIRTVS EXERCITVS ROMANORVM, the bravery of the Roman army.

Julian the Apostate presiding at a conference of sectarians by Edward Armitage, 1875

Introduction to Oration I

Julians training in rhetoric left its mark on all his writings, but technically speaking his work as a Sophist is comprised in the three panegyrics (Orations 13) and the prose Hymns (Orations 45). Oration 1 was considered his masterpiece and was used as a model by Libanius. It was written and probably delivered in 355 a.d., before Julian went to Gaul. The excuse of being an amateur is a commonplace () in this type of epideictic speech. He follows with hardly a deviation the rules for the arrangement and treatment of a speech in praise of an emperor ( ) as we find them in Menanders handbook of epideictic oratory written in the third century a.d. The speech is easily analysed. First comes the prooemium to conciliate the audience and to give the threads of the argument, then the praises of the emperors native land, ancestors, early training, deeds in war ( ) and in peace ( ), and the stereotyped contrasts with the Persian monarchs, the Homeric heroes, and Alcibiades. In the two last divisions the virtues of Platos ideal king are proved to have been displayed by Constantius, his victories are exaggerated and his defeats explained away. Then comes a description of the happy state of the empire and the army under such a ruler, and the panegyric ends abruptly without the final prayer () for the continuance of his reign, recommended by Menander. This peroration has evidently been lost. The arrangement closely resembles that of Oration 3, the panegyric on the Empress Eusebia, and the Evagoras of Isocrates, which Julian frequently echoes. Julians praises were thoroughly insincere, a compulsory tribute to a cousin whom he hated and feared.

Panegyric in Honour of Constantius

I have long desired, most mighty Emperor, to sing the praises of your valour and achievements, to recount your campaigns, and to tell how you suppressed the tyrannies; how your persuasive eloquence drew away one usurpers bodyguard; how you overcame another by force of arms. But the vast scale of your exploits deterred me, because what I had to dread was not that my words would fall somewhat short of your achievements, but that I should prove wholly unequal to my theme. That men versed in political debate, or poets, should find it easy to compose a panegyric on your career is not at all surprising. [2] Their practice in speaking, their habit of declaiming in public supplies them abundantly with a well-warranted confidence. But those who have neglected this field and chosen another branch of literary study which devotes itself to a form of composition little adapted to win popular favour and that has not the hardihood to exhibit itself in its nakedness in every theatre, no matter what, would naturally hesitate to make speeches of the epideictic sort. As for the poets, their Muse, and the general belief that it is she who inspires their verse, obviously gives them unlimited license to invent. To rhetoricians the art of rhetoric allows just as much freedom; fiction is denied them, but flattery is by no means forbidden, nor is it counted a disgrace to the orator that the object of his panegyric should not deserve it. Poets who compose and publish some legend that no one had thought of before increase their reputation, because an audience is entertained by the mere fact of novelty. Orators, again, assert that the advantage of their art is that it can treat a slight theme in the grand manner, and again, by the use of mere words, strip the greatness from deeds, and, in short, marshall the power of words against that of facts.

If, however, I had seen that on this occasion I should need their art, I should have maintained the silence that befits those who have had no practice in such forms of composition, and should leave your praises to be told by those whom I just now mentioned. Since, on the contrary, the speech I am to make calls for a plain narrative of the facts and needs no adventitious ornament, I thought that even I was not unfit, seeing that my predecessors had already shown that it was beyond them to produce a record worthy of your achievements. For almost all who devote themselves to literature attempt to sing your praises in verse or prose; some of them venture to cover your whole career in a brief narrative, [3] while others devote themselves to a part only, and think that if they succeed in doing justice to that part they have proved themselves equal to the task.

Next page