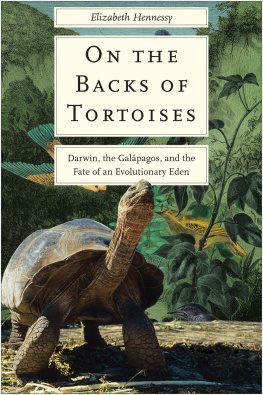

O N THE B ACKS OF T ORTOISES

Published with assistance from the Louis Stern Memorial Fund.

Copyright 2019 by Elizabeth Hennessy. All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Frontispiece: A giant tortoise wades in a pond at Campo Duro in the highlands of Isabela Island, July 2018. (Photo by the author)

Set in Scala type by IDS Infotech Ltd., Chandigarh. India. Printed in the United States of America by.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019936401

ISBN 978-0-300-23274-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for JPH

C ONTENTS

P REFACE AND A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

When I tell people in the United States, where I was born and live, that I do research in the Galpagos archipelago, their faces usually light up. I imagine they are picturing sun-drenched tropical islands inhabited by gigantic tortoises and playful sea lions. They usually ask whether I have been to this world-renowned vacation spotindeed, I am fortunate to have visited several times. Then they often ask me something that for a long time surprised me: Where do you stay when you visit the islands? Its a practical questionone that I think comes from a desire to picture me there. But it took me a while to understand why they were interested in what I saw as a rather banal detail. What I realized, though, after many versions of this conversation, is that it is common among North Americans to believe that the archipelago is uninhabited. That would make my answer much more exciting: Might I camp on a remote island like biologists or spend my time on a ship cruising the archipelago, as many tourists do? But my answer never lives up to the adventure that I think people want to hear about. They often seem a bit deflated, and surprised too, when I tell them that I stay in hotels or rent apartments for longer stays. When I explain that the islands have several towns that are home to some thirty thousand people, I feel like I am throwing a wet blanket on their imagination of a pristine wilderness. Sometimes a chagrined look crosses their faces, and they say something about how it is a shame that so many people now live in this place that really ought to be protected.

This is not the impression of the Galpagos that I hope to convey. It is striking that people who live so far from the islands have an emotional stake in themit speaks to the power of our imaginations of this storied place. Yet I am often dismayed by the assumption that the presence of towns must be detrimental and that people do not belong in this place that is often called Darwins natural laboratory of evolution. I understand why people think this way. It is a view influenced by news reports about a crisis of development in a place that most North Americans know from the many nature documentaries that take people on armchair vacations. But news reports and nature documentaries offer very partial views of life in the archipelago. They portray a world of extremeseither pristine nature or a crisis. Neither is the reality that I have seen.

The idea that people do not really belong in the Galpagos not only is held by outsiders, but also has seeped into the discourses of daily life on the islands, where it is not uncommon to hear people talk about themselves as invasive species or for longtime residents to lament the presence of newer migrants. An older Ecuadorian farmer once told me that he was concerned that so many people were moving to the island where he lived, lest the weight of the population cause the island to flip over. The interview was in Spanish, and I had to confirm with a friend later that I had heard the man correctly. I had. I think he meant it literally, as if the island was floating. But metaphorically, his fear was exactly in line with that of conservationists and global publics who fret that the islands have reached a tipping point of overpopulation and ecological destruction from which there can be no return.

In many ways, this book is my response to such ways of understanding the Galpagos. It is also my response to would-be tourists who have asked me whether its alright to visit the islands, or whether they would be better left alone. I write with North Americans in mind not because I believe the gringo perspective is universal, but rather because I am one. I write with them in mind also because North Americans perspectives are powerfulthey make up the largest market of Galpagos tourists, driving an industry that strives to meet visitor expectations. But this tour I offer is not one that highlights untouched wilderness. Nor do I offer lamentations about overpopulation on fragile island ecosystems. I am not unmoved by these concerns, but I think they are too quickly adopted and too comfortably rest on the false imagination that the Galpagos Islands are, or should be, pristine. In the pages that follow, I ask readers to slow down and to consider the long-standing, dense entanglements among people and nature that have shaped the Galpagos over the past five centuries, if not longer. Doing so, I believe, is crucial for safeguarding the future of this special place.

I am able to do this because of the many people in the archipelago who have opened their doors and shared their stories with me over the past twelve years. This book is based on research I conducted in the Galpagos during the summers of 2007, 2008, and 2009; for about six months during 20112012; and during short trips in 2015 and 2018. I owe them all a profound debt. I do not list them all here, in part to protect the privacy of sources. I owe particular thanks to Washington Tapia, without whose support and knowledge the project never would have gotten off the ground. My utmost thanks go as well to Don Fausto Llerena, Moises Villafuerte, Jos Pepe Villa, Wilfrido Michuy, Steve Divine, Fredy Cabrera, Paola Pozo, Swen Lorenz, Guido, Fernando Ortiz, Galo Quezada, Cruz Marquez, Sixto Naranjo, Arturo Izurieta, Washington Ramos, Graham Watkins, Danny Rueda, Oscar Carvajal, Felipe Cruz, Henri Moreno, Angel Arias, Johnson Arias, Rolando Loyola, Galo Torres, Washington Llerena, Domingo Navarrette, Carlos Zapata, and Ivone Torres. I wish I could have told in this book all the stories that you shared with me.

To the many Galpagos scientists who took time to speak with me, opening their labs and their living rooms, I thank you for your willingness to teach and talk with me and your patience for this book, which has been a long time coming. In particular, I thank Linda Cayot, Gisella Caccone, Steve Blake, Craig MacFarland, Howard and Heidi Snell, Tom Fritts, Peter Kramer, Gunther Reck, and Tjite de Vries. The first Galpagos researcher I talked to when I hatched the idea of a tortoise-focused study was James Gibbs, who turned out to be exactly the right person. This project would not have been possible without his support.

I also owe thanks to many archivists, historians, and scientists who work on Galpagos history. At the California Academy of Sciences I am grateful for the assistance of Alan Leviton, Barbara West, and Jens Vindum, who took me back into the storeroom to see taxidermied giant tortoises that have now sat on the institutions shelves for more than a century. In the archives, I would have been lost without the aid of Becky Morin, Christina Fidler, Rebekah Kim, and Seth Cotterell. I also thank Madeleine Thompson at the Wilderness Conservation Society; Alexandre Coutelle at UNESCO; Paul Martyn Cooper and Daisy Cunynghame at the British Natural History Museum; Erika Loor Orozco, the now late Elizabeth Knight, and Edgardo Civallero at the Charles Darwin Research Station; and archivists at the American Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian Institution. At the San Diego Zoo and Safari Park, thank you to Amy Jankowski, Kim Lovich, Tommy Owens, Jenna Lyons, and Oliver Ryder.

Next page