Contents

2017 Random House Ebook Edition

Copyright 2003 by Thomas Levenson

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Bantam Dell, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, in 2003.

St. Francis Einstein of the Daffodils by William Carlos Williams, from The Collected Poems: Volume I, 19091939, copyright 1938 by New Directions Publishing Corp. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Einstein quotations copyright 19792002 by Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Princeton University from The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

Ebook ISBN9780525508953

randomhousebooks.com

v4.1

a

Praise for

EINSTEIN IN BERLIN

A frighteningly vivid picture of the political and cultural upheavals that shook GermanyOne of historys most absorbing periods, refracted in the career of a key figure. Kirkus Reviews

An excellent account of both the human and the scientific sides of the scientist during the most crucial years of his life. St. Petersburg Times

Meticulously researched, Levensons work is a marvelous addition to extant Einstein biographies. Booklist

Of value to all who wish to comprehend modern science in its cultural context, Levensons sensitive and considered book assays the creativity and chaos conjured up by two of the most provocative proper nounsEinstein and Berlinto have emerged from the dizzying heights and debasing horrors of the twentieth century. Timothy Ferris, author of Coming of Age in the Milky Way and The Whole Shebang

Vividly portrays the scientist at work and provides a lively narrative of the eraexcellent. Publishers Weekly

Told with insight and flourish. Library Journal

This extraordinarily well-crafted and deeply engrossing book smoothly combines physics, history, and a sympathetic portrait of Einsteins personal life.Altogether exemplary. National Public Radio, Boston (WBUR)

For Henry and Katha

In memory of Rosemary Montefiore Levenson 19271997

CONTENTS

Prologue

THE ADORATION

It begins with a familiar story, the tale of the magi.

In the summer of 1913, two men came from the (north)east to Zurich, bearing gifts. In their own spheres, the two were kings. One of them, Walther Nernst, a small, round, funny, self-absorbed man, was a brilliant experimental chemist. The other, tall and lean, bespectacled, with a neat mustache and a precise elegance of manner, was Max Planck, inventor of the quantum theory and the most admired physicist in Germany.

They came from Berlin, the kaisers capital, a boomtown, the center of the world, if ones world was theoretical science. Zurich was no backwater, with its universities and its wealth, but Berlin had the talent and the ambition. Yet Planck and Nernst boarded their train and made the journey, bringing tribute, coming as supplicants. They came to adore a thirty-four-year-old man of obscure origins whose work had burst upon the world of physics as a revelation. In 1913 Albert Einstein was barely eight years into his career as a physicista generation junior to the reigning giants of his fieldyet he was already acknowledged as the first among equals, the dominant theoretical mind of his day. The two Germans went to Zurich; the magi traveled to the manger. They brought both gifts and praise. But this time, they sought something in return: Albert Einstein, in Berlin.

They did not stint on treasure. To snare Einstein, Planck and Nernst offered him election as the youngest member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, the German Empires elite scientific society. They promised him a faculty appointment at the University of Berlin under terms most professors can only dream of: no teaching obligations whatsoever, with the right to lecture as he pleased. They completed their homage with the gift of the directorship of his own physics institute, to be built soon under the umbrella of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes. And all this came with a specially funded salary of twelve thousand deutsche marks, the maximum payable to a Prussian professor.

It was, on its face, an absurdly generous propositiona position specifically tailored for Einstein, intended for him alone, offered him by two of the men he most admired. The subtext was clear: this was the promised land, a place not only of praise but of freedom, both intellectual and financial. Above all Planck and Nernst held out the lure of entry into the charmed circle, the community of the best and brightest that lay in wait in Berlin. Should he go? How could he not? And yetnot so fast. Dazzled but not blinded, Einstein told the two Germans they would have to wait. He needed a little more time, a night to sleep on it. Planck and Nernst acquiesced and left their quarry still uncaught.

In Switzerland on a summer night in 1913, two men, modern magi, waited upon the pleasure of the young prince. Planck and Nernst emerged from their night in limbo and then killed a few more hours on a sightseeing expedition by train. Einstein had promised to greet them on their return, holding a flower. If it were white, he was turning them down. If red, he would come to Berlin.

Midday in Zurich. The city flows around each side of the long lake. The bridges span the river, flowing through the heart of town near the railway station. Einsteins university stands just up the hill to the north of the main station, a grand, vaguely classical building. A little funicular tram runs from its plaza down to the tangled intersection at the center of town. At the turn of classes, students and professors jam in for the two-minute ride into town. A train pulls in beneath the vault of the station. Two men in early middle age step out of a carriage. They look anxiously down the length of the train for a younger man. A photograph from that time shows himdark, curly, close-cropped hair, deep-set eyes, cleft chin, a dark soft suit, arms crossed. The camera missed the edge of humor, but caught the confidence. The jokester appears on the platform. The older men look to his hands. They see the flower. It is red.

A LBERT E INSTEIN CELEBRATED his thirty-fifth birthday on March 14, 1914. The day passed without fanfarethere are no cards or letters in the record conveying either congratulations or thanks. He left Zurich one week later, detouring on the way to Berlin through Leyden and Haarlem in the Netherlands for physics talk with some of his favorite colleagues. He traveled alone. His wife, Mileva Maric, and his two young sons, Hans Albert and Eduard, had left before him on a vacation that he chose to avoid. He arrived in Berlin at the beginning of April.

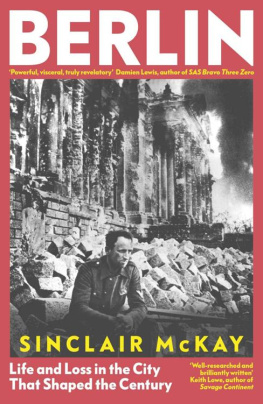

Albert Einstein in Berlin! For all the inducements laid before him, there was still something absurd about the idea. Einstein, after all, had renounced his German citizenship two decades earlier, preferring statelessness to the prospect of mandatory service in the German army. From the other side, Planck and Nernst had, in essence, bought him to be an ornament for the kaisers capital. As Einstein himself put it, the two men looked at him as if I were a prize hen or a rare postage stamp. Neither side ever made the mistake of seeing this as a love match. Each sought something from the other, and the story of that bargain, how it was kept and then broken illuminates one of the great mysteries of the twentieth century. The mystery is this: what happened to mutate the ostentatiously civilized imperial metropolis that Einstein entered in 1914 into the city perched on the edge of the abyss that he left for good at the end of 1932, just three weeks before Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany? It is no coincidence that Einsteins time in there tracks that transformation so precisely. Rather, his experience in Berlin can be seen as measure of the place. It was almost as if he were a kind of human Geiger counter tracing Berlins state and fate at any moment for those eighteen crucial yearsuntil that moment came when it was simply no longer possible for Einstein to survive there.