All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Image credits appear on .

Names: Levenson, Thomas, author.

Title: Money for nothing: the scientists, fraudsters, and corrupt politicians who reinvented money, panicked a nation, and made the world rich / Thomas Levenson.

Description: First edition. | New York: Random House, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020001521 | ISBN 9780812998467 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780812998474 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: EnglandEconomic conditions18th century. | Stock exchangesEnglandHistory18th century. | Debts, PublicEnglandHistory18th century.

Cover image: Great Britain 1720 guinea Ira & Larry Goldberg Auctioneers/Lyle Engleson

I NTRODUCTION

the great Follies of Life

L ONDON, 1719

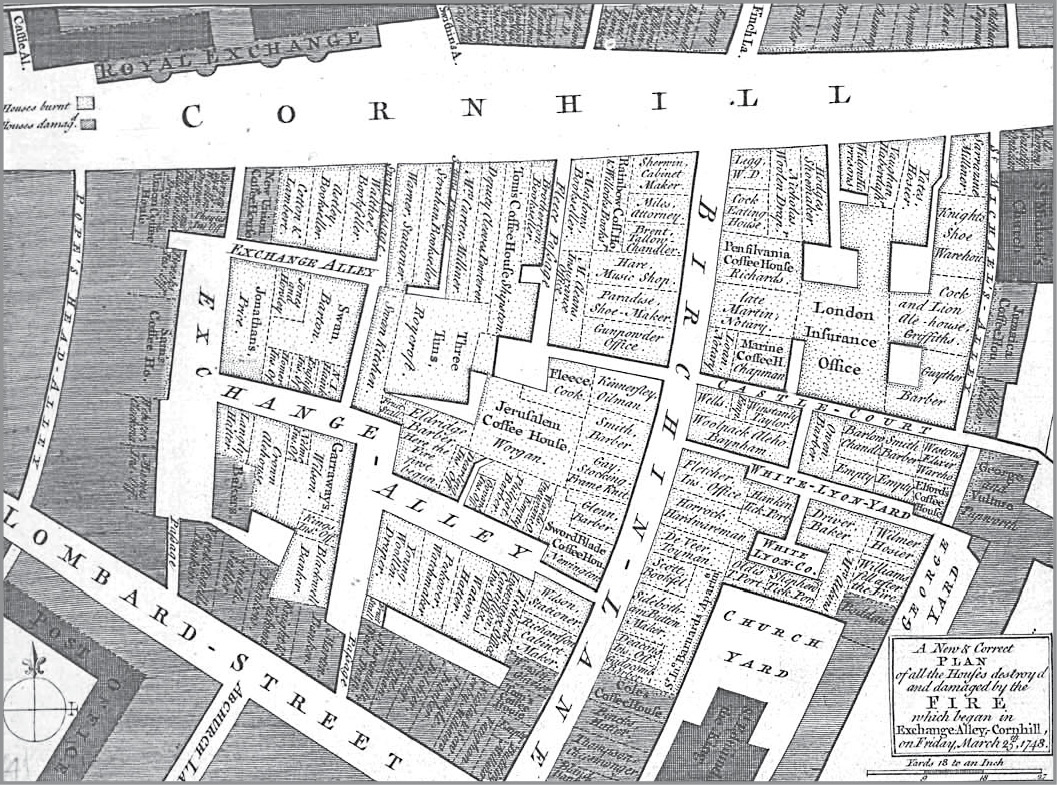

The year had begun well enough for Londons stock traders, working from their corner of the city, a narrow passage called Exchange Alley. Buying and selling sharesdealing not in things but in numberswas still new to the city. There was no fixed marketplace for traders in paper. So those who had mastered what was to many still a very dark art concentrated in a few taverns and inns, at Garraways, a coffeehouse that catered to the gentry, and more of them just around the corner at Jonathans, the rival coffeehouse that saw the most feverish trade in all the new ways in which it was possible to makeor bemoney.

Exchange Alley in its early-eighteenth-century layout

For journalist, propagandist, and gadfly Daniel Defoe, Jonathans and the rest were familiarand dangerous: dens of iniquity. Defoe had been warning his fellow Britons about the perils of the Alley for almost three decades. Now, near midsummer, he was ready with his most desperate alarm yet, a pamphlet titled The Anatomy of Exchange Alley, written in the voice of a jobber, or unlicensed dealer in stocks. In part, the pamphlet served as a kind of travel story, leading its readers on a journey to an exotic spot. Exchange Alley was an island in miniature. It could be walked in a minute or two: Stepping out of Jonathans [Coffeehouse] into the Alley, you turn your Face full South, moving on a few Paces, and then turning Due East, you advance to Garraways; from thence going out at the other Door, you go on still East into Birchin-Lane, and then halting a little at the Sword-Blade Bank to do much Mischief in fewest Words, you immediately face to the North, enter Cornhill, visit two or three petty Provinces there in your way West. There, a few hundred paces at most, and the visitor would be almost done: Having Boxd your Compass, and saild round the whole Stock-jobbing Globe, you turn into Jonathans again. Home again!but not in safe harbor, for the jobber concludes that as most of the great Follies of Life oblige us to do, you end just where you began.

And what folly it was! Defoe painted the risk faced by any reckless soul foolish enough to wander into Jonathans, in the tale of a navely avaricious countryman who encounters a couple of con men. They ply him with rumors, urge him to trade on their insiders knowledge, and surgically extract his entire fortune: his Coach and Horses, his fine Seat and rich Furniture, all sold to make good the Deficiency.

That was typical of Exchange Alley, Defoe warned his readers. It fostered a compleat System of Knaverya Trade founded in Fraud. Its tricks were hardly new, of course. In some form, theyre as old as human desire, as the book of Proverbs attests: The getting of treasures by a lying tongue is a vanity tossed to and fro of them that seek death. But this hopeful, nervous year of 1719 held something new, a scheme more ambitious than anything previous attempted by the devilish denizens of the Alley. The South Sea Company had opened for business in 1711. The firm had never really managed to do the work implied by its name, shipping goods and slaves to the Spanish ports of South America. Instead, it played in what was then just being born, a marketplace for credit, all the notes and bonds and much stranger inventions that the British government was using to build its ever-growing mountain of debt. For several years, the South Sea Company itself had nibbled around the edges of this market, completing a handful of minor deals, but its directors now aimed at a vastly more ambitious projectone that would, if it worked, solve Britains borrowing problem once and for all. They proposed a heroic attempt at what we would now call financial engineeringtaking the whole of the national debt, accumulated over a seemingly endless series of wars, and turning it into shares of a private companytheirswhich could be traded back and forth at will in the nascent stock exchange. In its partisans view, that would be the saving of the nation. Alternatively, as the skeptical Defoe warned, the clever men of Exchange Alley had figured out a way to get rich off of the public interest: they were ready, as Occasion offers, and Profit presents, to Stock-jobb [buy and sell] the Nation, couzen [trick] the Parliament, ruffle the Bank, run up and run down Stocks, and put the Dice upon the whole Town.

Stock-jobb the nation. That was the crux of Defoes polemic: schemes like this transformed the national debta public necessityinto a form that could be manipulated for private profit. That was, he argued, if not treason itself, then treacherys nearest cousin: Is not all that is taken from the Credit of the Publick, on such an Occasionis not every Step that is taken in Prejudice of the Kings Interesta plain constructive Treason in the Consequences of it?

In the most straightforward account of the events that were to comeknown to history as the South Sea BubbleDefoe would be proved right. In the year 1720, every Briton with two shillings to rub together, it seemed, would hear of the South Sea Company, would buy into its promises, and would be dazzled, for a time, at the prospect of riches beyond imagining. Half of Europe would too, and for a very great many it would end in ruin.

A ND YET, SEEN with enough distance (and a comfortable remove from those lost fortunes), its clear that Daniel Defoe was also wrong. What would happen in Exchange Alley over the next year wasnt simply the work of a Trade founded in Fraud, born of Deceit, and nourished by Trick, Cheat, Wheedle, Forgeries, Falshoods. The South Sea Bubblethe headlong rise and the sudden collapse of Londons nascent stock marketwasnt the original sin of early modern capitalismor rather, it was never only that.