The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

The first ideas for this book took shape in the summer and fall of 2013, while I was recovering from a severe illness that kept me bedridden for much of that time. Fortunately, I was blessed by a loving community of family, friends, and neighbors who provided comfort in times of anguish and a responsive sounding board when I could think about future endeavors. I am deeply beholden to all those dear souls and wish to acknowledge their vital role both in smoothing my recovery and helping me envision the contours of this book.

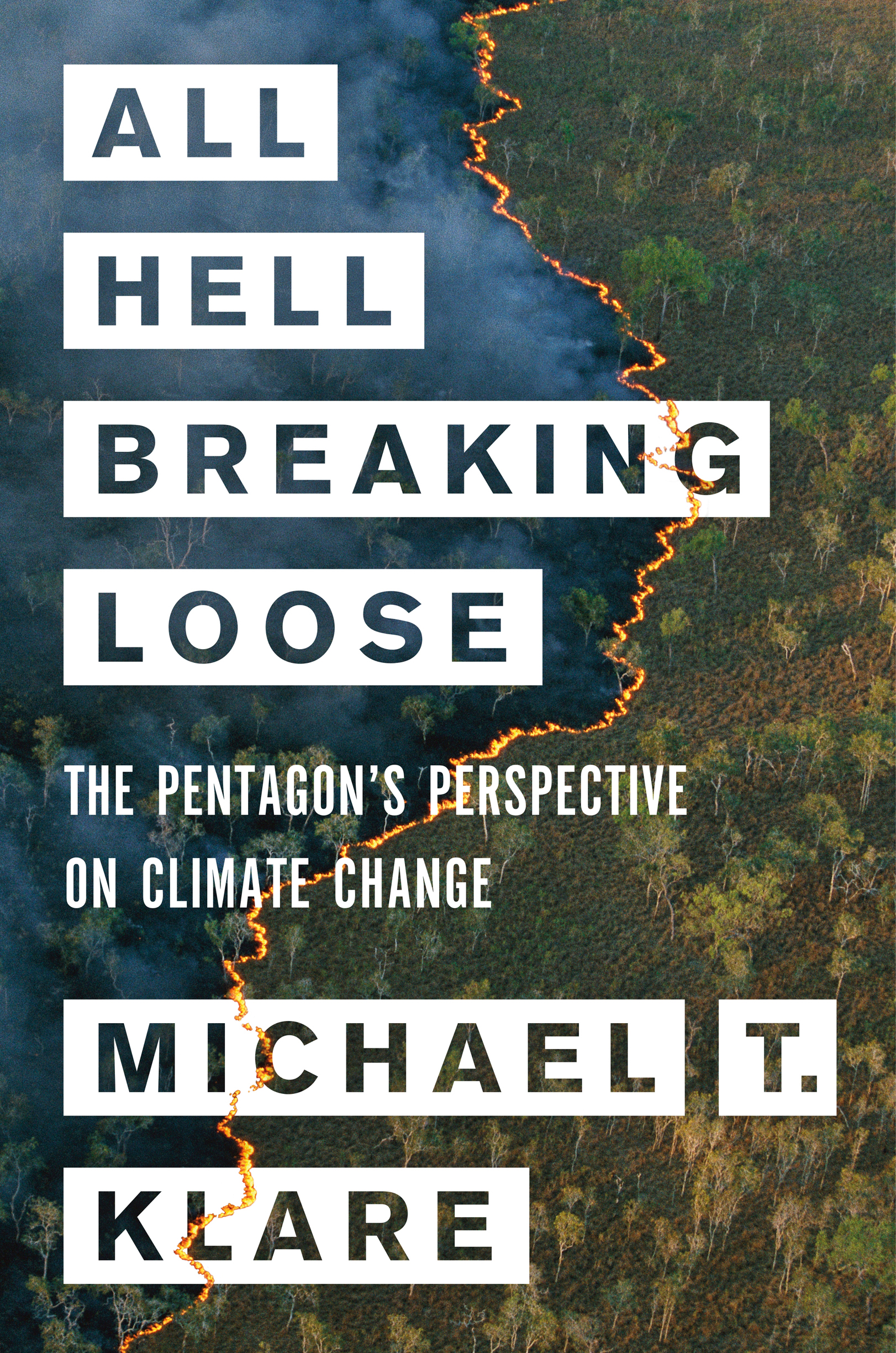

My gratitude begins with my wife, Andrea Ayvazian, who did more than anyone else to help me cope with my illness and then undertake the research and writing that culminated in All Hell Breaking Loose. I will be eternally grateful for her support during those difficult times and thereafter. Also critical during the hardest times was the support of our son, Sasha Klare-Ayvazian, and my siblings, Karl and Jane Klare. All three undertook numerous visits and cheered me on. I also wish to acknowledge the careful attention I received from my physicians, Joanne Levin, Timothy Parsons, and Henry Rosenberg. More than provide needed medical care, they offered the caring regard that gave me the confidence to overcome my distress.

As I was recovering, I was fortunate to have a close circle of friends who let me prattle on about my ideas for a new book that would address the issues of climate change, resource scarcity, and national security. Foremost among these are Jim Cason, Tom Engelhardt, Gerald Epstein, Betsy Hartmann, Katrina vanden Heuvel, Laura Reed, Seth Shulman, Adele Simmons, Daniel Volman, Cora Weiss, Barry Werth, and my former student Juecheng Zhao, who tragically passed away in 2018. I cannot recall how many conversations I had with these loyal friends, but I can state with certainty that their patience in listening to and commenting on my ideas represents a significant contribution to this book.

Of equal importance is the role played by my editors at Metropolitan Books, Sara Bershtel and Grigory Tovbis. Both reviewed various early proposals for a book on these issues and helped me narrow the frame to the topic as it stands today. I appreciate not only their critical guidance in this process, but also in their continued supportextended over many yearsfor my research and writing.

As I proceeded deeper into the research and writing of this book, many people offered vital help and suggestions. I am particularly indebted to several former military officers and officials who afforded me their time early in this process, helping me to better understand the militarys stance on climate issues. These include, most notably, Michael Breen, a former Army officer who served two tours of duty in Iraq; Sharon Burke, former assistant secretary of defense for operational energy plans and programs; John Conger, former principal deputy under secretary of defense (comptroller); Dr. Leo Goff of the CNA Corporation, a former Navy nuclear submarine commander; Sherri Goodman, former deputy undersecretary of defense for environmental security; and Major Danny Sjursen, a former instructor at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. I also benefited from conversations with members of the staff and advisory board of the Center for Climate and Security, a nonpartisan institute aimed at broadening public and congressional awareness of the links between climate change and U.S. national security. Equally beneficial has been my participation in the Working Group on Climate, Nuclear, and Security Affairs, a project closely associated with the Center for Climate and Security.

Until my retirement from teaching in June 2018, I served as the Five College Professor of Peace and World Security Studies, based at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts. In addition to teaching at Hampshire, I also taught classes at the other four members of the Five College Consortium: Amherst College, Mount Holyoke College, Smith College, and University of Massachusetts, Amherst. During my thirty-four years of teaching, I benefited enormously from constant interaction with students at the Five Colleges, as well as my many valued colleagues there. I particularly wish to acknowledge the many deep conversations over lunch and coffee with such esteemed colleagues as Aaron Berman, Margaret Cerullo, Javier Corrales, Omar Dahi, Sue Darlington, Vincent Ferraro, Elliot Fratkin, Peter Haas, Kay Johnson, Kavita Khory, Jonathan Lash, Sura Levine, Jon Western, Gregory White, and Andrew Zimbalist.

Many researchers at other institutions have also enriched my understanding of the issues raised in this volume. I particularly wish to acknowledge the contributions of those Ive had the opportunity to interact with at scholarly meetings, including Simon Dalby of Balsillie School of International Affairs in Canada, Corey Johnson of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Shannon OLear of the University of Kansas, James A. Russell of the Naval Postgraduate School, and Stacy VanDeveer of the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

For the past two years, Ive had the privilege of serving as a senior visiting fellow at the Arms Control Association in Washington, DC. Ive benefited enormously from my collaboration with ACAs staff and from the opportunity to learn more about the connections between nuclear weapons, international security, and climate change.

Lastly, I wish to acknowledge the generous support provided by the Samuel Rubin Foundation over the years for my research and educational endeavors. While serving as director of the Five College Program in Peace and World Security Studies, I was fortunate to receive a grant from the Rubin Foundation for support of research and teaching on the links between climate change, war, and conflict; among other things, that grant enabled me to attend several scholarly meetings, greatly enhancing my understanding of the topic.

So many other people helped me formulate my approach to this subject just by letting me talk about it that Im sure Ive neglected to mention some, for which Im truly sorry. I cannot recount all the conversations I had with students and colleagues at the Five Colleges where I gained some new insight, but I will remain eternally grateful for those interactions, and the many others with friends in Western Massachusetts, in Washington, and around the world.

Shortly after assuming the presidency in 2017, Donald Trump rescinded Executive Order 13653, Preparing the United States for the Impacts of Climate Change, a measure that had been signed by President Barack Obama in late 2013. The Obama order, steeped in the science of climate change, instructed all federal agencies to identify global warmings likely impacts on their future operations and to take such action as deemed necessary to enhance climate preparedness and resilience. In rescinding that order, Trump asserted that economic competitivenessinvolving, among other things, the unbridled exploitation of Americas oil, coal, and natural gas reservesoutweighed environmental protection as a national priority. Accordingly, all federal agencies were instructed to abandon their efforts to enhance climate preparedness and to abolish any rules or regulations adopted in accordance with Executive Order 13653. Most government agencies, now headed by Trump appointees, heeded the presidents ruling. One major organization, however, carried on largely as before: the U.S. Department of Defense.