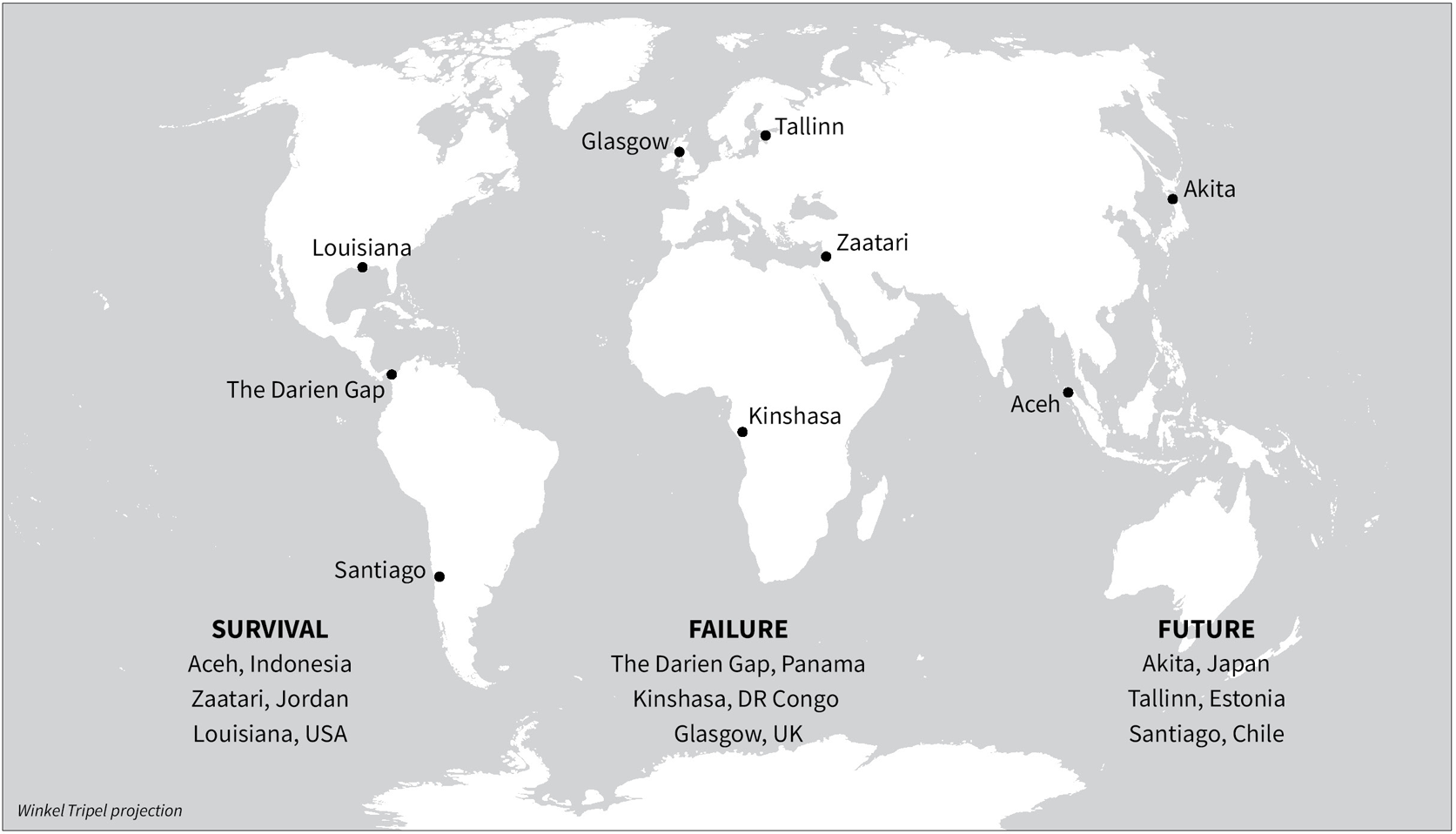

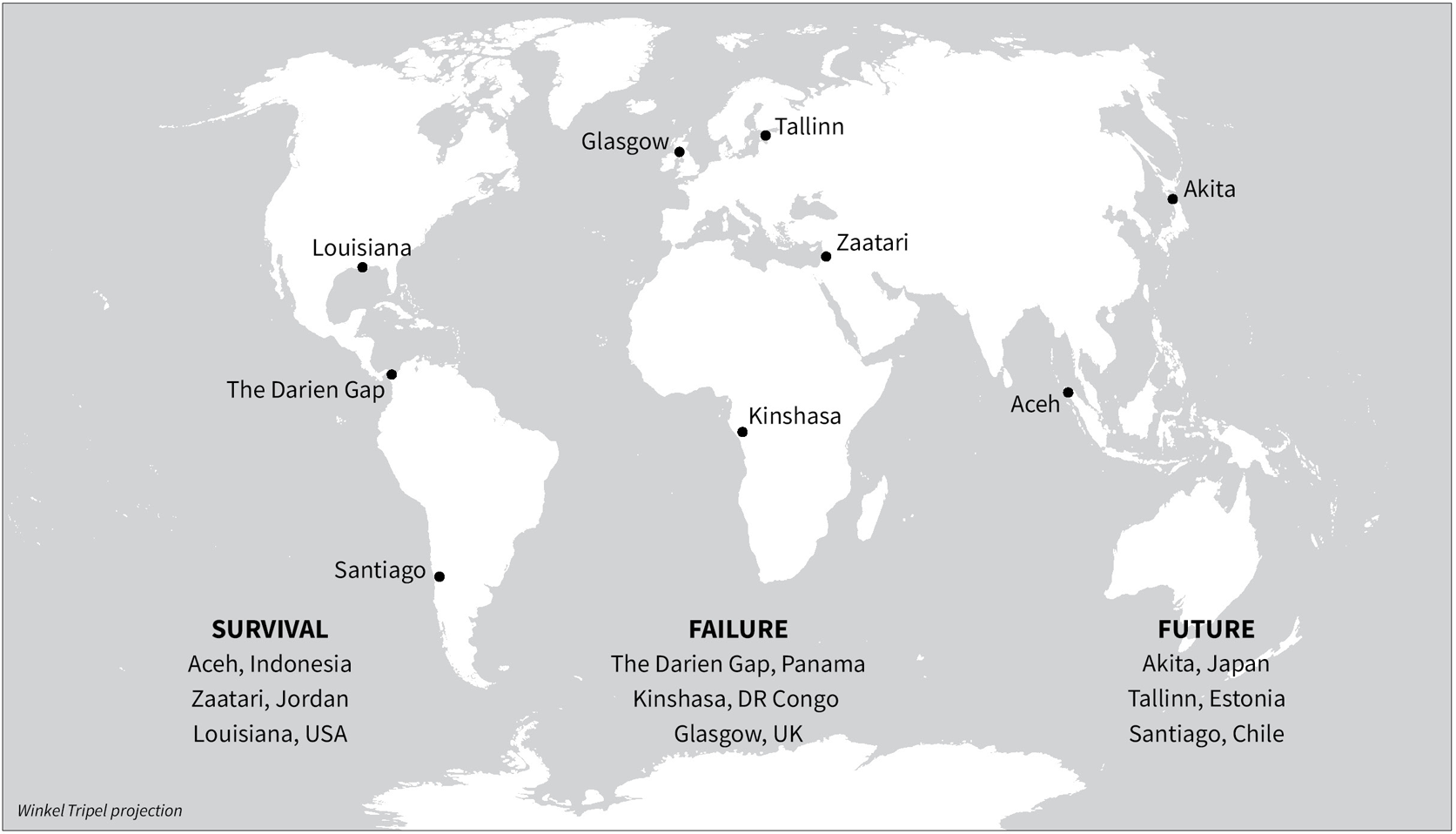

EXTREME ECONOMIES

SURVIVAL, FAILURE, FUTURE

LESSONS FROM THE WORLDS LIMITS

RICHARD DAVIES

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

6163 Uxbridge Road, London W5 5SA

penguin.co.uk

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Bantam Press

an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright Richard Davies 2019

Cover photograph Shutterstock

Richard Davies has asserted his right under the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781473552302

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

To Dr Richard Boyd and Mr Anthony Courakis, with thanks

Introduction

Economics in extreme places

Nature is nowhere accustomed more openly to display her secret mysteries than in cases where she shows tracings of her workings apart from the beaten paths.

William Harvey,

De Motu Cordis, 1628

RESILIENCE ON THE BEACH

As Suryandi recounts the morning of 26 December 2004, his strongest memories are of the terrifying sounds the tsunami made. It was a Sunday, and he had been busily preparing his restaurant, situated in prime position on the beach at Lampuuk, Aceh, for the coming days trade. When he heard a petrified fisherman shouting that a thick fog was rising from the ocean on the horizon, he headed down to the waters edge to see what the commotion was about. The reef, usually underwater, was exposed, and out on the edge of the bay two fishing boats had run aground in a spot that was normally a deep channel. He stood and watched until he saw the wave hit a headland a mile to the north. It sounded like a bomb had exploded, and Suryandi knew he was in trouble. He ran for his motorbike and opened the throttle, flying inland up narrow village lanes. By that point the air was full of screams and prayers, he says. There was no time to stop and check on his family and friends as he pushed on for higher ground. Behind him he could hear the wave. It sounded like an aircraft was chasing him.

Tsunami survivors in Aceh remember three waves and say the second was by far the worst. Suryandi watched it from the broadcasting tower of a local television station, which he had climbed up after racing inland. Water from the first wave had engulfed everything, he says, but homes and gardens remained, shops and cattle sheds were still intact. The second wave thundered in like the first, but was accompanied by sharper sounds of demolition loud snaps and crunches as trees were uprooted and buildings were destroyed. The third wave was far quieter, its rumble quickly giving way to a deep whooshing as the sea water began to drain back to the ocean. As the water receded, the local mosque appeared, but nothing else did. Every home was gone, every business flattened; all the fishing boats were smashed and the cattle had been swept away. Then, a final sound fell on Lampuuk, which Suryandi describes as the worst experience of his life there was complete silence.

Today on Lampuuk beach, Suryandi has a new restaurant. It is called Akun and sits, like the first one, in prime position at the head of the bay. His speciality is fresh fish, cooked over the glowing embers of coconut shells and served with local pickles. Like other Acehnese tsunami survivors, Suryandi ignored advice to relocate away from the coast and instead returned quickly to his village to rebuild his life. He started with nothing, building a shack made from driftwood into a thriving business. His account of that terrible day, on which he lost his mother, fiance and many of his friends, is one of grief and mourning. But like other Acehnese, he has another story to tell: one of ingenuity, determination and, in a way, triumph. Suryandi faced an extreme challenge, the type of which few people have come up against, yet through resilience and adaptation he bested it. My mission in Aceh was to find out how locals had rebuilt their communities so quickly, what role the economics played in their astonishing resilience, and what the rest of us could learn.

THREE EXTREMES: FAILURE, FAILURE AND FUTURE

The idea that the extremes of life offer important lessons is an idea widely used by scientists. In the field of medicine its founding father is Dr William Harvey, a London-based anatomist working in the seventeenth century. Harvey saw the value in examining odd and rare cases, with the remarkable life story of Hugh Montgomery a fine example. As a child, Hugh suffered a riding injury: the left side of his torso smashed so badly when he fell from his horse that his ribcage fell away, leaving part of his heart and lungs uncovered. Miraculously the boy survived a metal plate in place of ribs was used to protect his vital organs. By carefully removing the plate, Harvey was able to examine Hugh, and recorded how the movement of his heart came at the same time as the pulse in his wrist. It gave the doctor a unique window on human anatomy and was evidence for a controversial idea he was seeking to prove that blood circulated continuously around the human body.

Harvey was mocked by his peers, but as centuries passed, the importance of his most famous finding blood circulation became clear and the value of his methods respected. Other medics showed those who survived following bodily damage could offer valuable insight. In 1822 a young Canadian, Alexis St Martin, survived an accidental shooting and lived with a hole in his abdomen; direct observation of how his digestive system worked became an important foundation of gastric physiology. And in 1848 a railroad labourer in Vermont, Phineas Gage, miraculously survived an explosion which propelled a metal rod through his skull; the record of his life following the accident how his abilities and moods changed became a groundbreaking study of how the brain works. The miraculous resilience of these extreme patients all damaged in some way, yet all surviving offered lessons that could be applied when thinking about how more normal, healthy human bodies functioned.

A related tradition exists in engineering. It began in the mid-1800s after a series of tragic industrial and transport accidents. The Industrial Revolution had pushed materials to their limits in the UK, factories collapsed and boilers exploded; France was shaken by a rail tragedy in which a train derailed due to a snapped axle, claiming 52 lives. These disasters became public scandals, dominating politics and spurring a new branch of scientific investigation as engineers began to conduct in-depth studies of why things were going so wrong. The Scots excelled in this discipline and foremost among them was David Kirkaldy. Trained as an engineer, Kirkaldy devoted much of his life to studying why materials buckled and bent under pressure. He saw such value in the examination of failure that he designed a huge hydraulic machine to push metal samples until they snapped and sheared, and curated a small museum in which to display the fragments. When Britain suffered its worst disaster of the nineteenth century the 1879 collapse of the Tay Bridge it was Kirkaldy who was called in to get to the bottom of what had gone wrong.