Copyright 2020 by Bruce Goldfarb

Cover and internal design 2020 by Sourcebooks

Cover design by Richard Ljoenes

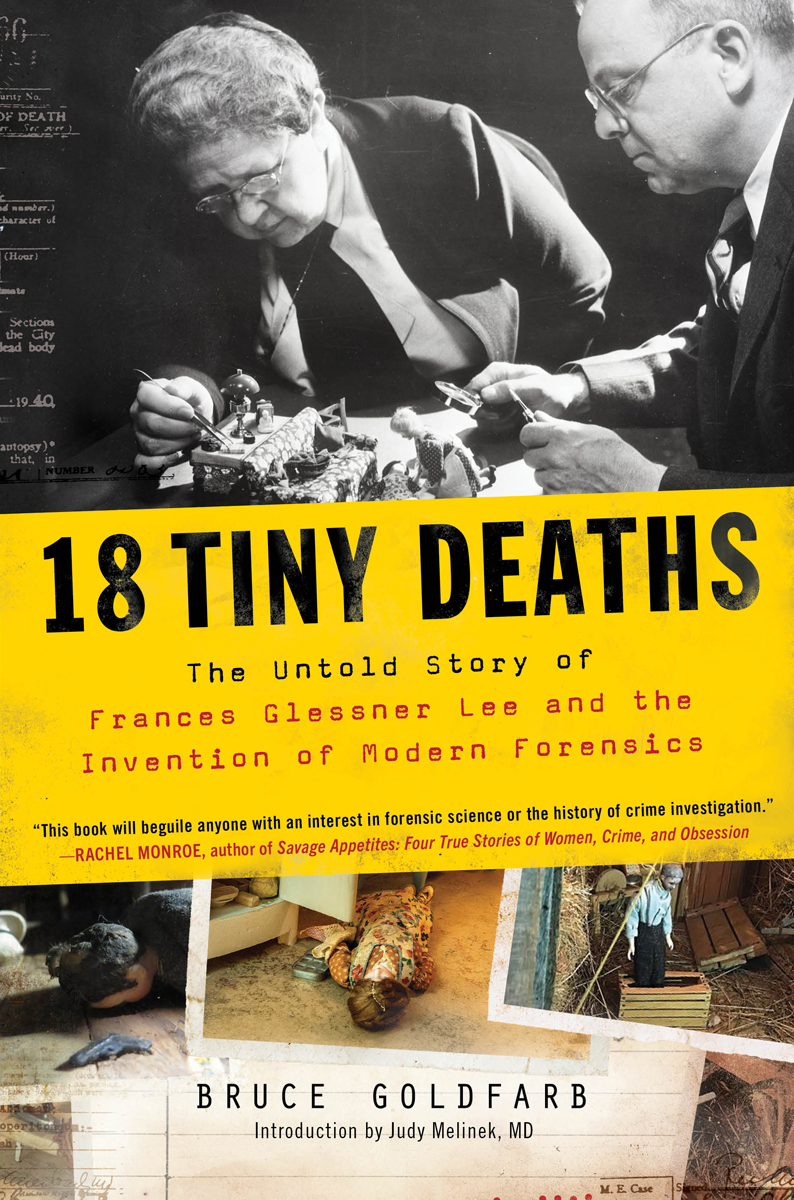

Cover images Frances Glessner Lee and Alan R. Moritz working on furnishings for the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death ca. 1948. Photograph by Gil Friedberg. From the Department of Legal Medicine Records, ca. 18771967 (inclusive). M-DE06. Harvard Medical Library in the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Internal design by Danielle McNaughton

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. From a Declaration of Principles Jointly Adopted by a Committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers and Associations

All brand names and product names used in this book are trademarks, registered trademarks, or trade names of their respective holders. Sourcebooks is not associated with any product or vendor in this book.

Published by Sourcebooks

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the publisher.

For Bridgett, Kaya, and Quinn

The investigator must bear in mind that he has a twofold responsibilityto clear the innocent as well as to expose the guilty. He is seeking only factsthe Truth in a Nutshell.

Frances Glessner Lee

CONTENTS

KEY CHARACTERS

THE GLESSNER FAMILY

John Jacob Glessner

Sarah Frances Macbeth Glessner Wife of John Jacob Glessner, known as Frances Macbeth

John George Macbeth Glessner Son of John Jacob and Frances Macbeth Glessner, known as George

Frances Glessner Lee Daughter of John Jacob and Frances Macbeth Glessner, known in childhood as Fanny

GLESSNER FAMILY FRIENDS

George Burgess Magrath, MD Harvard classmate of George Glessner, medical examiner for the Northern District of Suffolk County

Isaac Scott Designer, craftsman, and artist who made furniture and decorative objects for the Glessners

HARVARD MEDICAL SCHOOL

James Bryant Conant President of Harvard University, 19331953

C. Sidney Burwell, MD Dean of Harvard Medical School, 19351949

Alan R. Moritz, MD Chairman of the Department of Legal Medicine, 19371949

Richard Ford, MD Chairman of the Department of Legal Medicine, 19491965

OTHERS

Roger Lee, MD Prominent Boston internist and personal physician of George Burgess Magrath and Frances Glessner Lee, to whom he was not related

Alan Gregg, MD Director of the Medical Sciences Division of the Rockefeller Foundation, in charge of funding projects to improve medicine

Erle Stanley Gardner Bestselling author of Perry Mason novels

INTRODUCTION

Judy Melinek, MD

I FIRST ENCOUNTERED F RANCES G LESSNER Lees dioramas as a young doctor in 2003, when I traveled to Baltimore to interview for a position at the Maryland Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. The chief, Dr. David Fowler, asked if I had seen the Nutshell Studies. I told him, honestly, that I had no idea what he was talking about. Fowler then escorted me into a dark room and switched on the lights. Pushed into a corner, some hidden under sheets to keep the dust off, were a bunch of little boxes, and inside those, enclosed in plexiglass, I discovered a precious and intricate world of violence and death.

The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death are miniature death scenes. I scrutinized them. In one of the tiny rooms, I noticed the dotted pattern on the tiled floor and the incredibly precise floral wallpaper. Another showed a wooden cabin with a kitchen and bunk beds. There were snowshoes in the attic, a pot on the counter. I played with dollhouses as a girl and would regularly beg my father to drive us to the miniatures store hours away from our home in order to purchase supplies for my own tiny world, but I had never seen dollhouses this sophisticated before. To make plates for my dolls, I would pop out the plastic liner inside bottle caps. The plates in the Nutshell Studies were made of porcelain. Porcelain! The labels on the cans stacked on the kitchen shelves and the headlines on the newspapers were legible. I couldnt stop peering at the details.

Among those details, of course, were the blood spatters on the wallpaper, the grotesquely charred remains of a body on a burned bed, a man with a purple head hanging from a noose. These were no ordinary dollhouses. This was not childs play. What was I looking at? Who made these? And the most compelling question: What had happened here, in each of these stories frozen in miniature?

I had come to the interview in Baltimore after two years of training as a forensic pathologist at the New York City Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. Part of my education there included going to death scenes with the medico-legal investigators from the office and learning what to look for at a scene and what I might find at the scene that would help inform my final determination of cause and manner of death in the sudden, unexpected, and violent stories we were tasked by law with investigating. This is how you learn death investigation anywherethrough on-the-job training.

Still, there was always something uncomfortably voyeuristic about entering someones home unannounced and going through their medicine cabinet, trash cans, and refrigerator as a part of the process of trying to find out why they were lying dead on the floor. The investigators at the New York City OCME were certified professionals, and they told me where to focus my attention and what to lookand smell and listen and feelfor. The medicine cabinet would hold evidence of the decedents ailments. A big bottle of antacids could mean they suffered from gastrointestinal problems, but they could also be a clue pointing to undiagnosed heart disease. Prescription drug bottles might indicate whether those medicines were being used as directed, underutilized, or abused. The wastebasket might have unpaid bills, eviction notices, or an abandoned draft of a suicide note. The refrigerator could be full of food or empty except for a single vodka bottle. If the food was fresh, so was the body, most likely. If it was rottingthen it could help us confirm the degree of decomposition we were observing in the decedent, in an effort to hammer down the time of death. Everything at a death scene is part of the story, and it is the details I would find there that mattered most. I couldnt interview the patient. The surrounding environment was the medical history I would rely upon the next day, in the morgue, when I would perform the forensic autopsy and add those findings to the findings from the scene. As my mentor, the late Dr. Charles Hirsch, long-serving chief medical examiner for the city of New York, taught all of us who were fortunate enough to work for him, the autopsy is only part of the death investigation.