Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

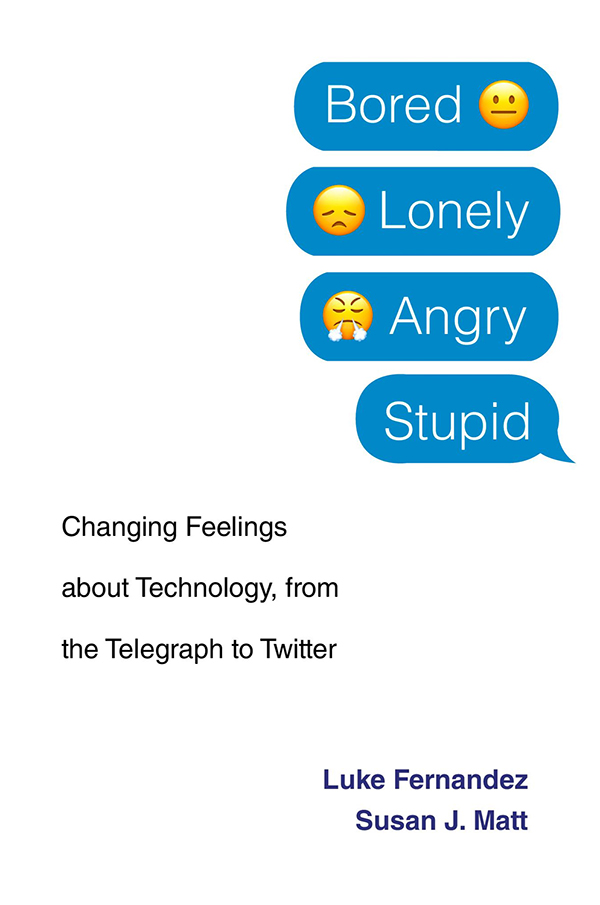

Bored, Lonely, Angry, Stupid

Changing Feelings about Technology, from the Telegraph to Twitter

Luke Fernandez

Susan J. Matt

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England 2019

Copyright 2019 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Jacket design: Tim Jones

978-0-674-98370-0 (alk. paper)

978-0-674-23937-1 (EPUB)

978-0-674-23938-8 (MOBI)

978-0-674-23936-4 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Fernandez, Luke. | Matt, Susan J. (Susan Jipson), 1967 author.

Title: Bored, lonely, angry, stupid : changing feelings about technology, from the telegraph to Twitter / Luke Fernandez and Susan J. Matt.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018043580

Subjects: LCSH: TechnologySocial aspectsUnited States. | TechnologyUnited StatesPsychological aspects. | Technological innovationsSocial aspectsUnited States. | Technological innovationsUnited StatesPsychological aspects.

Classification: LCC T14.5 .F385 2019 | DDC 303.48/30973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018043580

For Our Parents

James and Renate Fernandez

Joseph (19202007) and Barbara Matt

who taught us the joys and virtues of collaboration

Contents

On a bright November day, aboard a ferry crossing San Francisco Bay, Eli Gay found herself troubled by her thoughts. We were on the boat to Alcatraz. It was a beautiful day. And I was like Oh, I should take a picture of my cool life. I have to get a picture of this for Facebook! And that was kind of disturbing. A tax preparer living in Oakland, Eli had not been on Facebook that long, and she noted, I could already tell how it was changing my psychology. She recalled that Facebook was hard to leave aside: Say Im waiting for a ride. I have ten minutes to wait here; Ill go on Facebook and just start scrolling through things. And sometimes right before bed just one more page, just one more page. I could see the time and Id be like OK, bye. The top of the hour thats going to be the end. She was hooked.

Over the next seven years, Eli struggled with her feelings about social media, deactivating and reactivating her Facebook account multiple times. She was trying to figure out what her true self was, and how to present it, protect it, shape it, in the midst of the digital revolution.

What was clear from our conversation with Eli in 2016, and with the dozens of other people we interviewed for this book, is that Americans are living through a time of digital upheaval and rapid technological change. These changes, which have happened very quickly, are paradoxical, in that they seem ordinary but at the same time extraordinary. They have become integrated into so many aspects of life and often so seamlessly that at times people stop bothering to reflect on their significance. Yet, every so often, they are prodded to consider these transformations when they recognize in themselves a new emotion, a new behavior, as Eli did aboard the boat to Alcatraz, or, more commonly, when they read articles with provocative titles like Is Google Making Us Stupid?, Is Facebook Making Us Lonely?, and Is Social Media to Blame for the Rise in Narcissism? When those questions come to peoples attention, they are prompted to remember a time before the internet, and to consider how their phones and iPads, their laptops and selfie sticks, are changing their livesand themselves.

Bored, Lonely, Angry, Stupid grapples with that concern as it examines a new American emotional style that is taking shape today. It takes as its starting point six closely related questions, which have received a great deal of media attention and provoked significant debate: Is social media making people narcissistic? Is the internet causing loneliness? Have digital devices made individuals incapable of enduring boredom? Are people losing the ability to concentrate in an age of ceaseless distraction and multitasking? Are they so exposed to digital spectacles that they have become jaded and incapable of experiencing awe? Is social media fomenting anger? In essence, such questions point to a more fundamental query: have Americans feelings and their sense of self been radically remade by digital technologies?

This book examines those questions, but unlike other discussions of them, it places them in a broader historical context, as it considers how earlier generations coped with the innovations of their day, and how contemporary Americans are faring today. It investigates how women and men from a range of races and classes have felt about their technologies, and how their technologies have made them feel, from the telegraph to Twitter.

Ultimately, Americans emotional lives have changed dramatically in the last two hundred yearsand they are still changing today. As they struggle with narcissism, loneliness, boredom, distraction, anger, and awe, many in contemporary society are developing a new sense of self, a new emotional style, and a new set of expectations and ideas about what it means to be human.

For most of US history, Americans saw limits and constraints in themselves and in the world around them, and they had a more circumscribed set of expectations about what they could do, feel, express. As sixteen-year-old Caroline Cowles Richards wrote in her diary in 1857, what cant be cured, must be endured. Such an outlook reflected a belief that some hardships, feelings, and conditions could not be resolved or eliminated. This sense of limitations was reinforced by preachers admonitions, moralistic myths, and fables. In biblical tales like the fall of Adam, in classical myths such as the story of Icarus, and in sermons that reminded listeners of their own mortality, men and women learned of their fallibility and their finiteness, and heard again and again of the folly of transgressing certain imagined limits. This sense of limitedness was also present both in the vocabularies Americans used to describe themselves and in the emotional styles they used to express the self.

Consequently, when it came to their inner lives, earlier generations of Americans felt and experienced the world differently than people do today. Most expected that they sometimes would be lonely, for they believed this was part of the human condition. They knew they were mortal and would perish; clergy constantly reminded them that it was a vain, futile, and, ultimately, short life that humans led. Because of this, they should not be too absorbed with themselves, for the self was ephemeral. They also knew that as mortals they had finite physical and mental powersin fact, nineteenth-century medical authorities and religious leaders believed it was risky and perhaps immoral to try to exceed the natural limits of the brain and the body. Likewise, Americans expected drudgery and monotony and were not surprised when they encountered tedium. They often expressed anger but worried they might provoke Gods wrath if they displayed too much of their own. This widespread emotional style, which prevailed up through the early twentieth century, taught Americans that they were small, bounded, finite, limited, and it reminded them that in the universe there were forces larger and grander than themselves.