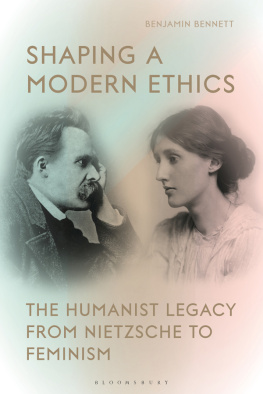

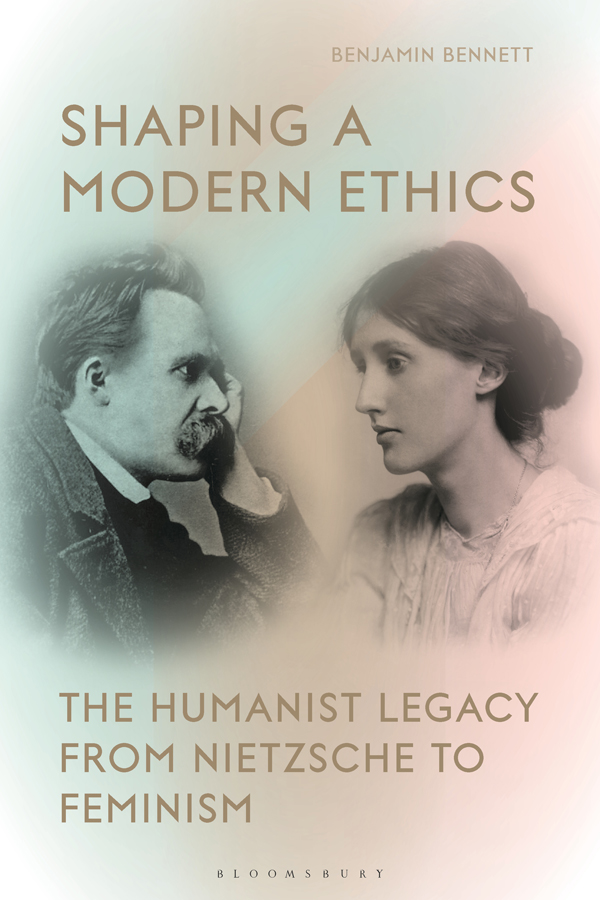

SHAPING A MODERN ETHICS

SHAPING A MODERN ETHICS

The Humanist Legacy from Nietzsche to Feminism

Benjamin Bennett

BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2020

Copyright Benjamin Bennett, 2020

Benjamin Bennett has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

For legal purposes the constitute an extension of this copyright page.

Cover design by Avni Patel

Cover images: Portrait of Freidrich Nietzsche by Gustav Schultze (1882). Portrait of Virginia Woolf by George Charles Beresford (1902).

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: HB: 978-1-3501-2285-7

ePDF: 978-1-3501-2286-4

eBook: 978-1-3501-2287-1

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters.

Also Available from Bloomsbury

The Ethical Imagination in Shakespeare and Heidegger , Andy Amato

Understanding Nietzsche, Understanding Modernism , ed. Brian Pines and Douglas Burnham

Nietzsche and Friendship , Willow Verkerk

Nietzsches Search for Philosophy: On the Middle Writings , Keith Ansell Pearson

Deleuze and the Schizoanalysis of Feminism , ed. Cheri Carr and Janae Sholtz

For Volker and Heike

Incipit vita nova

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION: ETHICS, LITERATURE, THE HUMAN, AND IRONY

Chapter 2

NIETZSCHE AND RORTY: THE ETHICS OF IRONY

Chapter 3

KANT AND LEIBNIZ

Chapter 4

LESSING: HISTORY, IRONY, AND DIASPORA

Chapter 5

LESSING AND FREUD: THEORY, WISDOM, AND THE SCOPE OF ETHICS

Chapter 6

HABERMAS, RORTY, AND MACHIAVELLI

Chapter 7

WOOLF, BACHMANN, WITTIG: TOWARD A FEMINIST ETHICS

I have been working on this project for a long time, and the number of friends and colleagues whose advice has helped me has grown far too large for me to mention them all here. I have also aged in the process, and if I did try to mention everyone, I would be sure to forget someone important. As far as it is in my power, however, I will not forget my debt to anyone. I am also grateful to the University of Virginia for research support and technical help. , my article Reason, Error and the Shape of History: Lessings Nathan and Lessings God, Lessing Yearbook , IX (1977), 6080. I am grateful to the British Psychoanalytical Society (incorporating the Institute of Psychoanalysis) for permission to use translations from The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud , ed. and trans. James Strachey et al., 24 vols. (London: Hogarth Press, 195374). And excerpts from A Room of Ones Own by Virginia Woolf, copyright 1929 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, renewed 1957 by Leonard Woolf, are printed by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company (all rights reserved) and of The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Vrginia Woolf. All efforts have been made to trace copyright holders. In the event of errors or omissions, please notify the publisher in writing of any corrections that need to be incorporated into future editions of this book.

| ADE | Association of Departments of English |

| ADFL | Association of Departments of Foreign Languages |

| BoT | Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy and The Genealogy of Morals , trans. Francis Golffing |

| DP | section number in the Discours preliminaire of Leibniz, Thodice |

| E | section number in the Essais proper in Leibniz, Thodice |

| ED | Habermas, Erluterungen zur Diskursethik |

| F | Kant, Kants Foundations of Ethics |

| GoM | Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, Ecce Homo , trans. Walter Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale |

| GW | Freud, Gesammelte Werke |

| JA | Habermas, Justification and Application: Remarks on Discourse Ethics |

| KSA | Nietzsche, Smtliche Werke: Kritische Studienausgabe in 15 Bnden |

| LM | Lessing, Smtliche Werke, Smtliche Schriften |

| MC | Habermas, Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action |

| MkH | Habermas, Moralbewutsein und kommunikatives Handeln |

| PEGS | Publications of the English Goethe Society |

| PMLA | Publications of the Modern Language Association |

| R | Kant, Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason and Other Writings |

| SE | The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud |

| WA | Goethes Werke , Weimarer Ausgabe |

Wittgenstein, Strawson, and We

In Cambridge, sometime in 1929 or 1930, Ludwig Wittgenstein composed and delivered a short lecture on ethics. It was not published during his lifetime and first appeared in 1965 in The Philosophical Review.

The lecture is concerned solely with the question of the existence of ethics as a more or less scientific discipline. Starting from G. E. Moores understanding of ethics as the general enquiry into what is good, Wittgenstein points out that words like good, valuable, important, right all have at least two clearly opposed senses, the trivial or relative sense on the one hand and the ethical or absolute sense on the other. The trivial or relative sense of such words always involves a factual state of affairs; something is good or right or important or valuable under specified circumstances or for a specified purpose. But the absolute or ethical sense creates problems for understanding.

The right road is the road which leads to an arbitrarily predetermined end and it is quite clear to us all that there is no sense in talking about the right road apart from such a predetermined goal. Now let us see what we could possibly mean by the expression, the absolutely right road. I think it would be the road which everybody on seeing it would, with logical necessity , have to go, or be ashamed for not going. And similarly the absolute good , if it is a describable state of affairs, would be one which everybody, independent of his tastes and inclinations, would necessarily bring about or feel guilty for not bringing about. And I want to say that such a state of affairs is a chimera. No state of affairs has, in itself, what I would like to call the coercive power of an absolute judge.

Which raises the question for Wittgenstein: Then what have all of us who, like myself, are still tempted to use such expressions as absolute good, absolute value, etc., what have we in mind and what do we try to express?

Next page