R oy M. Wallack is a Los Angeles Times health-and-fitness columnist and a contributor to many publications, including Outside , Mens Journal , Runners World , Competitor , Bicycling , and Mountain Bike . A former editor of Bicycle Guide and Triathlete magazines, he is the author of Bike for Life: How to Ride to 100 and The Traveling Cyclist: 20 Worldwide Tours of Discovery . Along with competing in innumerable running, cycling, and triathlon races, Roy has participated in some of the worlds toughest endurance events, including the Eco-Challenge and Primal Quest adventure races, the Paris-Brest-Paris, TransAlp Challenge, La Ruta de los Conquistadores road and mountain-bike races, and the TransRockies Run. He lives in Irvine, California with his tandem bike partners, wife Elsa and son Joey, and his running partner, Bruce the dog.

CHAPTER

THE BOSTON REVELATION

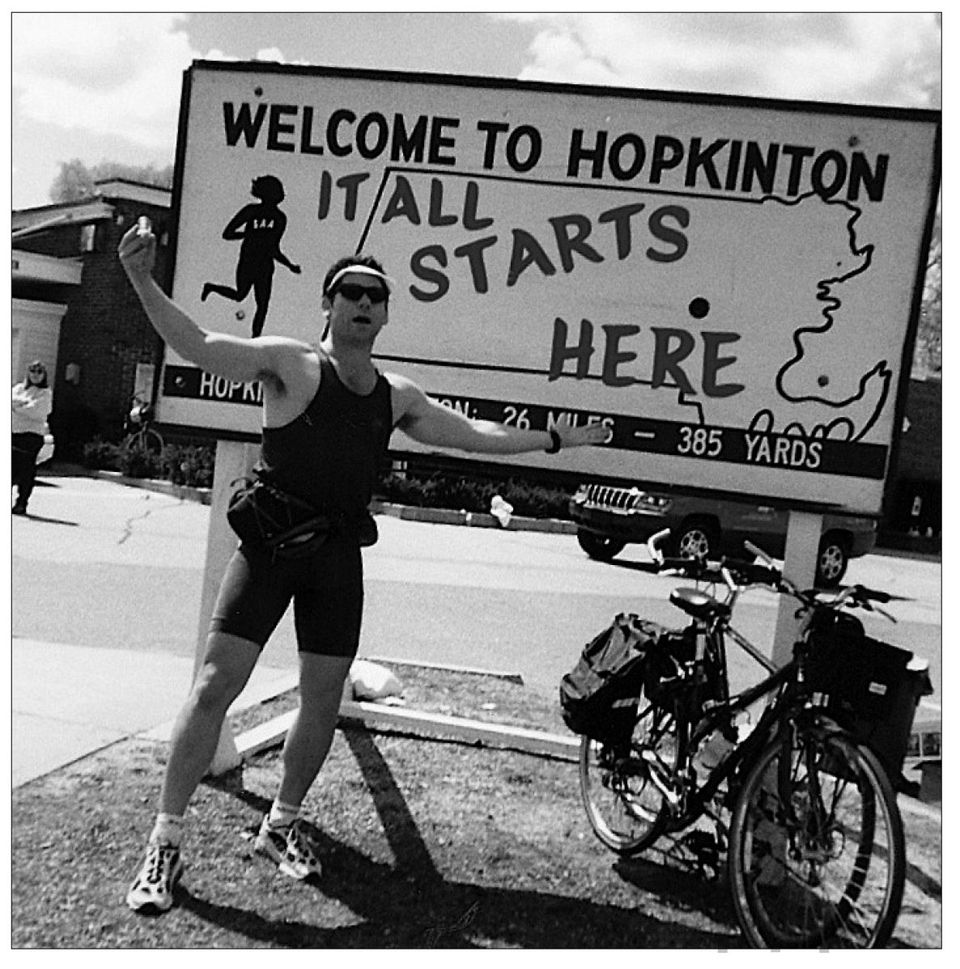

What better way to learn to run soft than in the worlds most famous race?

S hort strides. Rapid turnover. Landing under your center of gravity. Forget these three things, and you will be destroyed. I was desperate, so I listened closely as my friend Robert Forster, a physical therapist who runs Phase IV, a high-performance training center in Santa Monica, explained that my only hope of finishing the Boston Marathon was to completely change my running form. Right now.

After all, it was April 5, 1999. Boston was 14 days away. I had a non-refundable frequent-flyer ticket in hand, but I had not run in four months due to a shoulder wrecked in a bike crash and intense, searing pain in my left hip whenever I jogged a step. A doctor had just told me Id developed Pagets Syndromeexcess calcium buildup in the joint. He said it was caused by years of running, which he recommended I never do again.

So I had no choice. Your only hope of survival is to baby your muscles and connective tissue by minimizing impact and running softly, explained Forster, who got his start in physical therapy by readying and rehabbing two famous athletesworld-record 100-and 200-meter runner Florence Griffith FloJo Joyner and her world-record-setting heptathlete sister-in-law, 3-time Olympian Jackie Joyner Kersee. Running softly means no heel-striking, he said, just short, fast strides that keep your foot strike right under your body mass, your center of gravitynot out in front. The smaller steps take the workload and distribute it over more foot strikes, reducing the forces at each one. If you allow your strides to lengthen, youll fly through the air further and crash down harder, naturally heel-striking, and putting more leverage and stress on your muscles and tendons.

Miracle on Boylston Street? The author ran the soft-running gauntlet.

To picture it, think of the Road Runner, he added. His legs go in a little circle, and barely touch the ground. They go so fast they blur. You are going to shoot for a cadence of 180 strides per minute. Youre going to spin your legs like the Road Runner.

As Forster finished his lecture, Steve Tamaribuchi, a chiropractor visiting from Sacramento, handed me a strange pair of purple-colored plastic handgrips he had invented called the e3 Grips. They looked like whats left over after you squeeze your hand around a lump of clay.

You say youve got hip pain? said Tamaribuchi. Hold these as you run and itll straighten out your arm swing, which will reduce the excessive sway of your hips. I bet the pain will disappear.

Right , I thought, rolling my eyes. Im going to run with tiny little steps for 26 miles holding these funky purple handgrips .

An hour later, however, I was pinching myself. After leaving Forsters office, Id gone right to the gym and run 5 miles on the treadmillwith no pain. Facing a mirror, I could clearly see that my arms were swinging vertically, not crossing over my chest at an angle, just as like Tamaribuchi had said.

As a test, Id occasionally put the grips aside. Each time I ran without them, my hip would hurt again. Then, when I regripped, the pain would instantly disappear.

I was amazed. And I knew right then that the 103rd Boston Marathon would be one of the most interesting experiences of my life.

AFRAID NOT TO RUN SOFT

During the next 10 days, I alternated short-stride, rapid-turnover running with the elliptical machine, logged 34 total miles in 5 runs, and topped out with a 14-miler before beginning my taper and flying east. In the past, ramping up the mileage so quickly would have left me with pulled muscles, shin splints, and tendonitis. But now, on my most accelerated schedule ever, I simply felt great. Connective tissue, muscles, and hips were all perfectly pain-free.

Still, 26.2 miles seemed nuts to my friends, who had a tradition of flying in from all over the country every year to meet in Boston to run the marathon as banditspeople who hadnt met the qualifying times to officially run the race. They were amused by my little strides, weird grips, and lack of training. On an easy three-mile out-and-back to Jamaica Pond the day before the marathon, they placed bets on the mile Id quit, break down, or permanently injure myself at. Id been thinking of this as a neat experiment; they thought it was suicide. I started to worry.

By the time we arrived in Hopkinton the next day about an hour before the 12-noon start, I was scared to the point of paranoia. Clutching my Grips as if holding invisible ski poles, I jogged around the start area mouthing my soft-running mantra over and over: Short strides, rapid turnover, footfall under the bodys mass. People looked at me as if I was a religious fanatic praying for a miracle.

The miracle part was right. All the logical scenarios that played out in my head ended the same way: my muscles imploding 10 miles from the finish, leaving me a scorned, pathetic failure marooned miles from home. I wasnt necessarily worried about being an illegal runner anymorethere were hundreds of numberless bandits openly warming up around me, including a pair of fullsuited Blues Brothers imitators, and one guy with a turn-out piece of brown shopping-bag paper pinned to his shirt with the word bandit scrawled on itbut not being an official entrant still could be a problem. Id have no access to the pickup buses that ferry broken-down runners to the finish line in Boston, where my wife and kid would be waiting for hours.