Contents

Guide

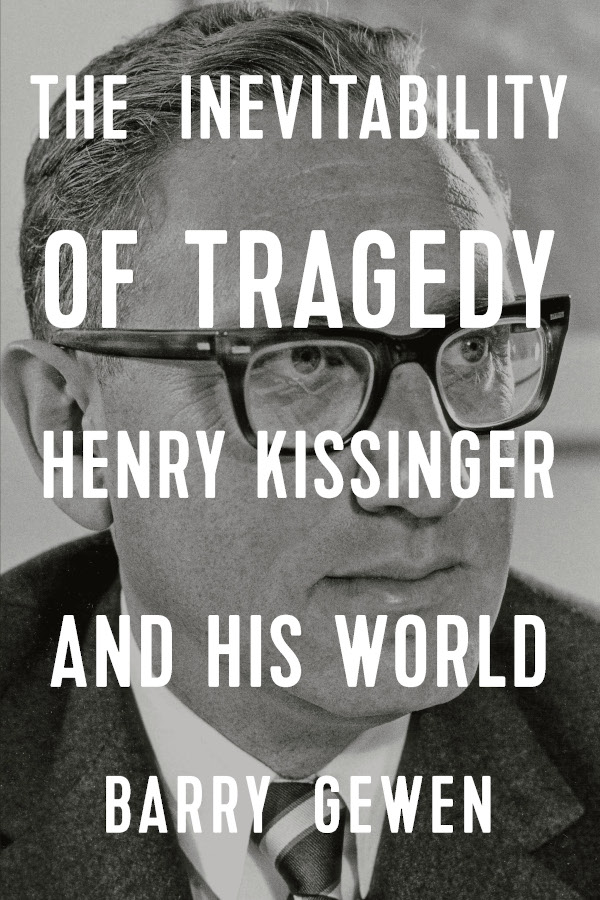

THE

INEVITABILITY

OF

TRAGEDY

HENRY KISSINGER

AND HIS WORLD

BARRY GEWEN

Copyright 2020 by Barry Gewen

All rights reserved

First Edition

Since this page cannot legibly accommodate all the copyright notices, constitute an extension of the copyright page.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Jacket design by Yang Kim

Jacket photograph: Shutterstock

Book design by Lovedog Studio

Production manager: Anna Oler

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN 978-1-324-00405-9

ISBN 978-1-324-00406-6 (eBook)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

To my colleagues, past and present, at the

New York Times Book Review

There are certain truths which the Americans can learn only from strangers or from experience.

ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE

One has to live with a sense of the inevitability of tragedy.

HENRY KISSINGER

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE IN THE FIRST PERSON

A COUPLE OF YEARS AGO, I WAS HAVING DINNER WITH A friend when he leaned across the table and whispered to me, Barry, Henry Kissinger is evil . He was in the middle of writing his own book on foreign policy, and in the course of a long friendship we had spent many mutually beneficial evenings discussing international affairs. It was not unusual for our conversations to run to 3 or 4 hours.

We approached policy issues differently. I tended to take a Realpolitik view, which is to say that I tried to reach conclusions based on the power relationships of a given situation. I attempted to assess how American national interest would be affected by a particular decision and to measure what was possible, not simply desirable. To put it another way: I thought it was important to distinguish between what was trueRealismand what one wished to be true. I was distrustful, even dismissive, of applying moral considerations in a field where abstract morality did not seem especially relevant. (I tended to keep in mind Justice Robert H. Jacksons admonition not to follow ones principles over a cliff: the Constitution, he once said, is not a suicide pact.) I certainly didnt believe in moral absolutes that outweighed all other considerations, national well-being foremost among them.

My friend put more emphasis on the place of ethics in foreign policy than I did and was always ready to remind me that without a moral component international affairs would degenerate into a Hobbesian world of all against all, and that in such a world only the bullies and gangsters would prevail. Limits had to come from something other than force, and if power was the only thing restricting policy decisions, there could never be an end to warfare. This was an especially dismal prospect, he pointed out, in a nuclear age. The point of a moral code was to put an internal brake on humankinds naturally aggressive tendencies, and the hope for peace was only possible if everyone agreed to behave according to universally accepted rules. I would reply that without the authority of a transcendent powerthat is, Godprescribing those rules and perhaps a belief in an afterlife where eternal punishment could be meted out to violators, no permanent agreement was possible, only temporary stopgaps devised by fallible human beings. And so we went round and round.

For all our differences, however, we were not only able to have fruitful discussions but also to find broad areas of agreement. The reason, I think, is that neither of us is an absolutist. We had our respective views, but we werent dogmatic about them. Foreign policy, after all, is a field that doesnt lend itself to straightforward black-and-white solutions. There were too many gray areas in which one had to accept uncertainty and to some degree fall back on guesswork. It is not mathematics.

And so my friend acknowledged that, despite his moral concerns, many issues required one to think in terms of power and national interest; he could be as much a Realist as I was when he thought the situation called for it. And I had to concede that without a moral component, foreign policy could be a rotten, blood-drenched business. I confessed that I didnt much like those leaders who thought only in terms of power, with no evidence of compassion. Moral considerations had to enter the picture at some point even if they werent the primary motivation for policy decisions. Because we were able to find so many points of overlap, our conversations didnt go round and round forever. Instead, after talking things through, we frequently found that we agreed on a number of questions, an ideal blending of Realism and morality.

But one subject where agreement proved to be impossible was on the impact of Henry Kissinger. He brought our discussions to a screeching halt. Not that we completely abandoned our flexibility: my friend was willing to recognize that Kissinger had made historic contributions (though, as I recall, he gave Richard Nixon more of the credit), and I was hardly about to argue for every decision that Kissinger ever made. Whats more, I didnt like the sometimes weaselly explanations Kissinger himself offered for his own policies. At times, it seemed, he was trying to defend the indefensiblelike approving of the wiretapping of his colleagues at the National Security Council or attempting to reinvolve an exhausted United States in the fighting in Vietnam after the signing of the 1973 treaty that, largely through his own efforts, had given America a way out. But insofar as my friend and I struggled to arrive at an overall assessment of the mans career, it was as if a line had been drawn in the sand. My friend was permanently stationed on one side, I on the other. Nothing that either of us could say would persuade the other to change his mind. In one sense, therefore, this book can be seen as an extension of our discussions from my point of view.

B UT THERE IS a larger and more urgent reason for this book: Kissinger has not held public office since 1977, but I believe his time has come round again, and today we dismiss or ignore him at our peril. He is more than a figure out of history. He is a philosopher of international relations who has much to teach us about how the modern world worksand often doesnt. His arguments for his brand of Realismthinking in terms of national interest and a balance of poweroffer the possibility of rationality, coherence, and a necessary long-term perspective at a time when all three of these qualities seem to be in short supply.

Whatever else it did, the Cold War provided coherence of a kind: the United States was faced with an implacable enemy, armed with nuclear weapons and an aggressive global ideology that compelled American policymakers to devise a basic strategy for their planning. For all the mistakes made at that time, George Kennans policy of containment worked for more than four decades. The United States won the Cold War.

For a brief moment after the collapse of the Soviet Union, it seemed that a different kind of coherence was possible: Americas role had become to foster the inevitable expansion of democracy around the world, sometimes by force. Peoples with different cultures and different values would be grateful for Washingtons interventions; they would greet our invading troops with flowers and candy. The United States was the indispensable nation, destined to lead. With the many disappointments that have occurred in the Middle East and elsewhere, this mission has obviously failed. Yet nothing has been found to replace it. How should America define its place in the world?