Prologue

HOW WASHING DISHES RESTORED MY INTELLECTUAL LIFE

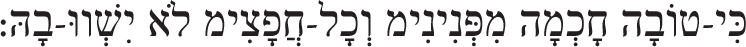

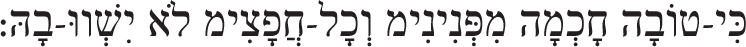

For wisdom is better than rubies;

And all that you may desire cannot compare with her.

PROVERBS 8:11

Midway through the journey of my life, I found myself in the woods of eastern Ontario, living in a remote Catholic religious community called Madonna House. We lived by a river that froze into flat, icy landscapes in the winter, giving off mist as it thawed and froze again. In summer the water warmed to allow swimming or boat trips through thick weeds up into the wild and empty vistas of the river valley. Our manner of life was rustic, as poor as it was hidden, thanks to the communitys deliberate commitment to poverty. We slept in dormitories, used water sparingly, wore donated clothing, and ate vegetables either in the short growing season or as the root cellar or the freezer permitted.

The work varied and was assigned under obedience. I was the baker for a time, stewarding the capricious yeast and the fire of the oven, emerging at the end of the day covered in dough, flour, and ash. I then worked in the handicrafts department, restoring furniture, repairing books, organizing materials, decorating for holidays. I joked that I was being trained as a nineteenth-century housewife. Next, I was assigned to the library; then to a long stint cleaning and researching donated antiques for the communitys gift shop. I shared in the common work of housecleaning and washing dishes, as well as planting, weeding, and harvesting vegetables. As in many such communities, we switched jobs often enough that no one could be fully identified with their work. This made it easier to see work not as a vehicle for achievement but as a form of service: talent and interest were valuable but ultimately irrelevant. Certainly, neither any of these jobs nor the basic approach to life was what I had spent the previous twenty years preparing for. From the age of seventeen until I left for Canada at the age of thirty-eight, I had been dedicated full time to institutions of higher learning, first as a student and then as a professor and a scholar of classical philosophy.

My life as a professional intellectual had its roots in my childhood. From my earliest memory I lived with books of all kinds. There were stacks on my bedroom floor and they lined the dusty walls of our Victorian house. My older brother taught me to read and infected me with an appetite for reading; my parents were both lovers of books, words, and ideas without professional training or support, amateurs in the original and best sense. San Francisco in the 1970s was a strange place for many famous reasons, but its basic commitment to leisure is clear to me only now that we have passed into a far less leisurely age. Reading and thinking for their own sake went along with outings to the stony beaches or dark mountain forests of Northern California, without a clear object or specialized skills or expensive equipment. The standard for success of an activity was enjoying oneself in fellowship with others; such endeavors included the arts and crafts projects that no one would ever buy, and musical performances whose value would evaporate at too great a distance from the campfire.

That natural foods were superior to processed ones was a hard fact to swallowI needed threats and wheedling to be induced to consume carob or brewers yeast or foul-tasting medicinal tea. But I required no convincing to find that learning was a joy. My family was fond of fierce arguments over matters of fact, when no one present knew what they were talking about: world records and body counts, the proper classification of living things, and the nature of a lunar eclipse. The dictionary, the encyclopedia, and the almanac were the final reference points by which the arguments were settled. These resolutions were never entirely satisfactory. In the reference books we found ammunition for yet further discussion and argument. Not one piece of knowledge that we sought or acquired was useful for any purpose whatsoever.

My brother and I pursued obsessions with wild animals, especially sea creatures. We knew all seventeen species of penguin and the feeding habits of whales. Large, blubbery sea lions sometimes surfaced at the local seashore; otherwise, we relied on books or visits to the local science museum, studying our beloved objects through whale skeletons or at the thick-glassed dolphin tank that replayed recorded dolphin sounds when we pressed a button at the side. We amassed a vast collection of stuffed animals, who formed a political community and elected a small walrus as president. We established a constitution for them, wrote civic anthems, and, of course, told stories. We imagined our way into the lives of animals, fusing animal and human capacities as children have always done.

Larger questions lurked unexpressed behind our sea of facts and our playful imagining. What is a human being? Is it enough to see, feel, eat, swim, squeak? Are we a part of nature, or somehow outside of nature? My father and I once discussed that question, sitting on a rock in a mountain stream on a camping trip, in the shade of clustered redwoods. It seemed unimaginable that we were like the forest, running water, or rock around us. Somehow a human being stands outside of the natural, and yet even a child knows that the time will come when breath is gone and all is overcome by weight, resistance, decay, and fermentation, our flesh traveling through the gullets of animals to become dirt and slime and dust.

My family did not undertake intellectual practices and concerns as a means to an end. They did not consider them to be preparation for life, but rather a way of spending ones time that had its worth in itself. Accordingly, they did not blink when I left home to study old books and fundamental human questions at a tiny liberal arts college on the East Coast, a secular school under the improbable religious name of St. Johns College. My parents did not ask me what use I would find the study of epic poems or ancient treatises on plants, whether it would help me to find my way in the world. Not that my choice was foreordained: my brother, for instance, pursued specialized training in biochemistry. But I needed neither prodding nor reassurance to study the liberal arts. The value of such an education, as one path among others, was simply obvious to us.

This first phase of my academic life began in spectacular growth and excitement. I loved my little college at first sight: the willows at the waters edge; the green lawn sloping down to them, suited for summer rolling and winter sledding; the colonial redbrick buildings that both charmed and startled me, fresh as I was from brick-free earthquake country. I was instantly at ease in the bare-bones classrooms, each furnished with only a large wooden table, old-fashioned caned chairs, and wraparound blackboards. Our classes proceeded without agendas, the discussion driven by the living questions that we and our teachers brought to the room. Accordingly, our conversations could flounder in indifference or lack of preparation; they could chug along steadily, building quiet momentum; or they could explode with the excitement of a newly discovered insight. I was enchanted by the honesty of the project: as the books were, as the questions were, as the human beings who participated were, so the discussion went. There was no artificial clarity or forced organization to soften the discomfort of the work of the mind, no cushion between us and the difficulties or dangers of inquiry or the thrill of discovery.