Contents

GENDER AT WORK IN VICTORIAN CULTURE

Personally, I have nothing against work, particularly when performed, quietly and unobtrusively, by someone else. I just dont happen to think its an appropriate subject for an ethic

Barbara Ehrenreich

Gender at Work in Victorian Culture

Literature, Art and Masculinity

MARTIN A. DANAHAY

Brock University, Canada

First published 2005 by Ashgate Publishing

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, 0X14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Martin A. Danahay 2005

Martin A. Danahay has asserted his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Danahay, Martin A.

Gender at work in Victorian culture.(The nineteenth century series)

1.English literature19th centuryHistory and criticism 2.Art, British19th century 3.Art, Victorian 4.Masculinity in literature 5.Masculinity in art 6.Sex role in literature 7.Sex role in art 8.Work in literature 9.Work in art 10.Great Britaincivilization19th century

I.Title

820.935309034

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Danahay, Martin A.

Gender at work in Victorian culture / Martin A. Danahay.

p. cm.(The nineteenth century series)

Includes index.

ISBN 0-7546-5292-0 (alk. paper)

1. English literature19th centuryHistory and criticism. 2. Working class in literature. 3. Literature and societyGreat BritainHistory19th century. 4. MenEmploymentGreat BritainHistory19th century. 5. Division of laborGreat BritainHistory19th century. 6. Working classGreat BritainHistory19th century. 7. Masculinity in literature. 8. Sex role in literature. 9. Working class in art. 10. Work in literature. 11. Men in literature. I. Title. II. Series: Nineteenth century (Aldershot, England)

PR468.L3D36 2005

820.93553dc22

2005007232

ISBN 13: 978-0-7546-5292-2 (hbk)

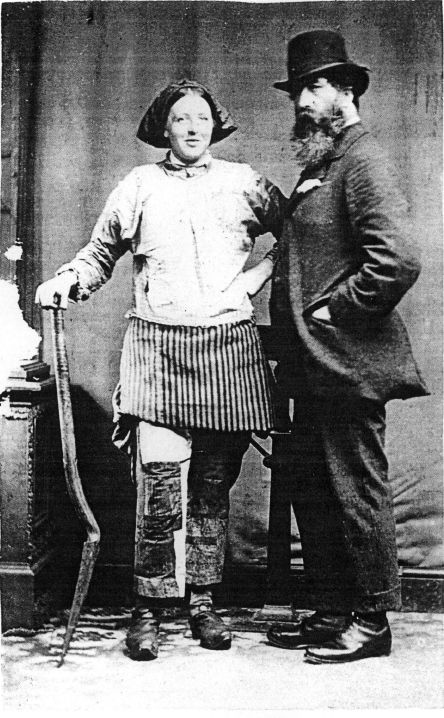

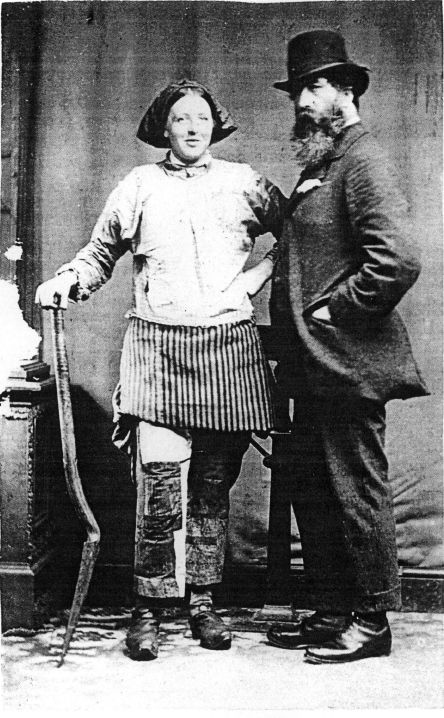

Arthur Munby and Ellen Grounds (1873)

Contents

Frontispiece Arthur Munby and Ellen Grounds (1873)

Plate section is located between pages

The aim of the series is to reflect, develop and extend the great burgeoning of interest in the nineteenth century that has been an inevitable feature of recent years, as that former epoch has come more sharply into focus as a locus for our understanding not only of the past but of the contours of our modernity. It centres primarily upon major authors and subjects within Romantic and Victorian literature. It also includes studies of other British writers and issues, where these are matters of current debate: for example, biography and autobiography, journalism, periodical literature, travel writing, book production, gender and non-canonical writing. We are dedicated principally to publishing original monographs and symposia; our policy is to embrace a broad scope in chronology, approach and range of concern, and both to recognize and cut innovatively across such parameters as those suggested by the designations Romantic and Victorian. We welcome new ideas and theories, while valuing traditional scholarship. It is hoped that the world which predates yet so forcibly predicts and engages our own will emerge in parts, in the wider sweep, and in the lively streams of disputation and change that are so manifest an aspect of its intellectual, artistic and social landscape.

Vincent Newey

Joanne Shattock

University of Leicester

Writing this book has provided links, both real and virtual, to many people. At UT Arlington Johanna Smith was both an invaluable colleague and an eagle-eyed reader of an earlier version of this manuscript, while Kevin Gustafson was a congenial lunch companion when I took breaks. As I worked on various parts of the manuscript I posted sundry arcane and obscure queries to the VICTORIA listserv and benefited from the generosity of list members who were unstinting with their time and knowledge. The faculty at Haverford College, especially C. Stephen Finley, provided stimulating feedback on a lecture I gave on my Victorian work at their invitation. Ann Colley also through her encouraging remarks after a presentation of my ideas on Ruskin and digging at a conference in Texas helped motivate me to finish that part of the project.

I could not have written this book without the scholarly models provided by James Eli Adams, Joseph Kestner and Herbert Sussman. The following pages are studded with references to their work as I often agree, occasionally disagree, but always respect the achievements represented by their publications. These guys were collectively a tough act to follow.

Across the Atlantic, Trev Lynn Broughton is a kindred spirit toiling in the fields of masculinity and autobiography and I follow her parallel scholarship with great interest and benefit. In a different but related project on Victorian masculinity that indirectly helped clarify some of my ideas in the following pages, David Amigoni has been the very model of a good bloke. Id also like to express my appreciation to Joanne Shattock and Vincent Newey for allowing my book to join the distinguished ranks of their Nineteenth Century Series and take its place alongside Andrew Dowlings monograph Manliness and the Male Novelist in Victorian Literature. Dowlings book on Victorian masculinity inspired me to submit my own manuscript to Ashgate, and I hope the series sees more titles in this area in the future.

Although I do not know who they are, I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers of my initial manuscript who asked such probing questions and goaded me into explaining my analysis more fully. I have endeavored to answer the challenges of their queries as I revised the book for publication, and if there are any deficiencies in the following pages it is entirely due to my own inability to rise to the level of excellence that they demanded. Im particularly grateful to them for having corrected my tendency to turn John Tosh (the eminent historian) into Peter Tosh (the reggae artist); although Im a big reggae fan, the following pages owe very little to Peter Tosh and a great deal to John Tosh.

At Ashgate I was fortunate to find an encouraging editor in Ann Donahue whose enthusiasm for this book made many years of labor worthwhile. One of the nightmares of working on such a huge topic as Victorian concepts of work is the fear that it may never actually see the light of day, and her support of this project was for me a dream come true.

My parents Jeannette and Michael Maddocks have helped tremendously by writing cheques when recalcitrant British institutions refused to take my credit card, and by keeping me supplied with copies of the