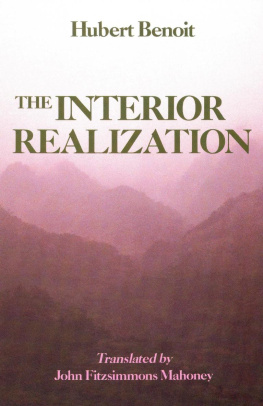

Copyright 1955 by Pantheon Books Inc.

333 Sixth Avenue, New York 14, N.Y.

First published in France in 1951 under the title of

LA DOCTRINE SUPRME

eISBN: 978-0-307-83195-8

v3.1

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

P HILOSOPHY in the Orient is never pure speculation, but always some form of transcendental pragmatism. Its truths, like those of modern physics, are to be tested operationally. Consider, for example, the basic doctrine of Vedanta, of Mahayana Buddhism, of Taoism, of Zen. Tat tvam asithou art That. Tao is the root to which we may return, and so become again That which, in fact, we have always been. Samsara and Nirvana, Mind and individual minds, sentient beings and the Buddha, are one. Nothing could be more enormously metaphysical than such affirmations; but, at the same time, nothing could be less theoretical, idealistic, Pickwickian. They are known to be true because, in a super-Jamesian way, they work, because there is something that can be done with them. The doing of this something modifies the doers relations with reality as a whole. But knowledge is in the knower according to the mode of the knower. When transcendental pragmatists apply the operational test to their metaphysical hypotheses, the mode of their existence changes, and they know everything, including the proposition, thou art That, in an entirely new and illuminating way.

The author of this book is a psychiatrist, and his thoughts about the Philosophia Perennis in general and about Zen in particular are those of a man professionally concerned with the treatment of troubled minds. The difference between Eastern philosophy, in its therapeutic aspects, and most of the systems of psychotherapy current in the modern West may be summarised in a few sentences.

The aim of Western psychiatry is to help the troubled individual to adjust himself to the society of less troubled individualsindividuals who are observed to be well adjusted to one another and the local institutions, but about whose adjustment to the fundamental Order of Things no enquiry is made. Counselling, analysis, and other methods of therapy are used to bring these troubled and maladjusted persons back to a normality, which is defined, for lack of any better criterion, in statistical terms. To be normal is to be a member of the majority partyor in totalitarian societies, such as Calvinist Geneva, Nazi Germany, Communist Russia, of the party which happens to be in power. For the exponents of the transcendental pragmatisms of the Orient, statistical normality is of little or no interest. History and anthropology make it abundantly clear that societies composed of individuals who think, feel, believe and act according to the most preposterous conventions can survive for long periods of time. Statistical normality is perfectly compatible with a high degree of folly and wickedness.

But there is another kind of normalitya normality of perfect functioning, a normality of actualised potentialities, a normality of nature in fullest flower. This normality has nothing to do with the observed behaviour of the greatest numberfor the greatest number live, and have always lived, with their potentialities unrealised, their nature denied its full development. In so far as he is a psychotherapist, the Oriental philosopher tries to help statistically normal individuals to become normal in the other, more fundamental sense of the word. He begins by pointing out to those who think themselves sane that, in fact, they are mad, but that they do not have to remain so if they dont want to. Even a man who is perfectly adjusted to a deranged society can prepare himself, if he so desires, to become adjusted to the Nature of Things, as it manifests itself in the universe at large and in his own mind-body. This preparation must be carried out on two levels simultaneously. On the psycho-physical level, there must be a letting go of the egos frantic clutch on the mind-body, a breaking of its bad habits of interfering with the otherwise infallible workings of the entelechy, of obstructing the flow of life and grace and inspiration. At the same time, on the intellectual level, there must be a constant self-reminder that our all too human likes and dislikes are not absolutes, that yin and yang, negative and positive, are reconciled in the Tao, that One is the denial of all denials, that the eye with which we see God (if and when we see him) is the same as the eye with which God sees us, and that it is the eye to which, in Matthew Arnolds words

each moment in its race,

Crowd as we will its neutral space,

Is but a quiet watershed,

Whence, equally, the seas of life and death are fed.

This process of intellectual and psycho-physical adjustment to the Nature of Things is necessary; but it cannot, of itself, result in the normalisation (in the non-statistical sense) of the deranged individual. It will, however, prepare the way for that revolutionary event. That, when it comes, is the work not of the personal self, but of that great Not-Self, of which our personality is a partial and distorted manifestation. God and Gods will, says Eckhart, are one; I and my will are two. However, I can always use my will to will myself out of my own light, to prevent my ego from interfering with Gods will and eclipsing the Godhead manifested by that will. In theological language, we are helpless without grace, but grace cannot help us unless we choose to co-operate with it.

In the pages which follow, Dr. Benoit has discussed the supreme doctrine of Zen Buddhism in the light of Western psychological theory and Western psychiatric practiceand in the process he has offered a searching criticism of Western psychology and Western psychotherapy as they appear in the light of Zen. This is a book that should be read by everyone who aspires to know who he is and what he can do to acquire such self-knowledge.

ALDOUS HUXLEY.

AUTHORS PREFACE

T HIS book contains a certain number of basic ideas that seek to improve our understanding of the state of man. I assume, therefore, that anyone will admit that he has still something to learn on this subject. This is not a jest. Man needs, in order to live his daily life, to be inwardly as if he had settled or eliminated the great questions that concern his state. Most men never reflect on their state because they are convinced explicitly or implicitly, that they understand it. Ask, for example, different men why they desire to exist, what is the reason for what one calls the instinct of self-preservation. One will tell you: It is so because it is so; why look for a problem where none exists? This man depends on the belief that there is no such question. Another will say to you: I desire to exist because God wishes it so; He wishes that I desire to exist so that I may, in the course of my life, save my soul and perform all the good deeds that He expects of His creature. This man depends on an explicit belief; if you press him further, if you ask him why God wishes him to save his soul, etc., he will end by telling you that human reason cannot and is not called upon to understand the real basis of such things. In saving which he approaches the agnostic who will tell you that the wise man ought to resign himself always to remaining ignorant of ultimate reality, and that, after all, life is not so disagreeable despite this ignorance. Every man, whether he admits it or not, lives by a personal system of metaphysics that he believes to be true; this practical system of metaphysics implies positive beliefs, which the man in question calls his principles, his scale of values, and a negative belief, belief in the impossibility for man to know the ultimate reality of anything. Man in general has faith in his system of metaphysics, explicit or implicit; that is to say, he is sure that he has nothing to learn in this domain. It is where he is most ignorant that he has the greatest assurance, because it is therein that he has the greatest need of assurance.